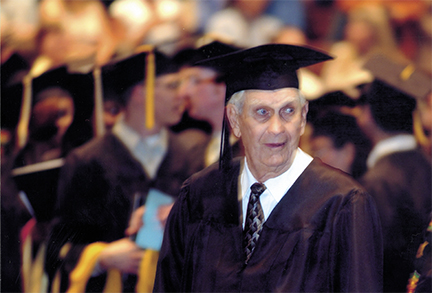

Shocker history to receive a degree. Cheered on by his wife and three

of their five children, he received his diploma during May graduation

ceremonies at the Kansas Coliseum.

Joe Stone walked across the stage at the Kansas Coliseum to pick up his long-awaited bachelor’s degree — and received a standing ovation from fellow graduates, faculty and those attending Wichita State’s commencement ceremonies for the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

Stone, a transplanted Kansan living in California, is the oldest person in Shocker history to receive a degree.

The 90-year-old journalist graduated, thanks to the work of WSU officials who helped him get credit for life experience and two friends in California who lobbied for several years on behalf of their friend. “Joe has been successful at everything he’s done,” says one of those friends, Hal Steward, a retired journalist and author. “This is the one thing in his life that he regretted not finishing.”

Stone and his wife Catherine were scheduled to attend graduation ceremonies in December 2002, but a hit-and-run accident in November seriously injured her and delayed their trip back to Wichita. In May, Catherine and three of their five children watched Stone walk across the stage to finish what he started in 1934. Stone — who six years ago was named honorary mayor of Borrego Springs, Calif., along with his wife, and who also is an honorary California forest ranger — recalls his time in Wichita with fondness. “The happiest years of my life,” he repeats often, “were spent at the University of Wichita.”

During the Watts Riots in Los Angeles, Joe Stone and a photographer were told to "hit the deck" if they heard gunfire. "Would you mind falling on top of me?" Stone asked his colleague.

Stone’s journalist pals in California, Steward and Hugh Crumpler, worked their contacts to get congratulatory letters sent to him on his graduation accomplishment. Notes came from the governors of California and Kansas, as well as congratulations on behalf of U.N. Secretary General Kofi Annan, British Prime Minster Tony Blair and the Queen, a Coast Guard admiral and Pope John Paul II. Former Kansas Gov. Bill Graves wrote, “You serve as an example of accomplishment that your fellow Kansans can take pride in.”

Charles Joseph Stone was the third of four children born in January 1913 in the back of his parents’ grocery store in Frizzell, Kan., in Pawnee County. His arrival boosted Frizzell’s population to 10. Joe, who grew up in the Burrton-Halstead area, started at the University of Wichita in 1934 under the College Student Employment Program, part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal.

“There were, as I recall, more than a hundred of us,” Stone says. “We were assigned to jobs on campus. I started with a pick and a shovel, removing dirt to extend the running track to 220 yards. Then I was assigned to handle the fine team of horses owned by the college, Dick and Dolly.” During the summer drought, he drove the team to haul water for the trees on campus. He was paid 30 cents an hour. He couldn’t make more than $15 a month.

During the week, he boarded with the college’s superintendent of grounds, Elmer Welch, who had two cows. Stone’s diet his first semester at college consisted mostly of milk he purchased from the man for a nickel a quart and cracked wheat he bought for a quarter a peck.

Stone enrolled as an English-journalism major. His work on the student newspaper, The Sunflower, attracted the attention of a professor, who had him transferred to his office. Stone worked on publicity for the college under the tutelage of veteran newspaperman Bliss Isely.

Stone’s new desk was next to a door that led to the college switchboard. He would open the door to ask for an outside line to call The Wichita Eagle and The Wichita Beacon, which were competing papers. One day, he opened the door and there, at the switchboard, was Catherine Bordner.

They met later on the steps of Fiske Hall to talk. Their first date was to see a movie, “Farmer Takes a Wife,” starring Henry Fonda. He later took her to the National Baseball Congress tournament, where he recalls watching Satchel Paige pitch. “We’ve been married 65 years,” Stone says proudly.

While still a student, Stone landed a job with the Wichita Police Department in 1937. He worked a four-hour night shift and took a full class load. That four-hour stint didn’t last long, however.

“If you weren’t any good, they let you go,” he explains. “If you were good, they soon had you working eight hours. You couldn’t do that and take 15 hours (of classes) and get any sleep.”

He became the police department’s primary detective and switched to day shift. His attendance in his WSU classes gradually tapered off. The last semester he was enrolled was in the spring of 1939. He left school 23 credits short of graduation.

Stone took a leave from the police department in May 1942 to join the Coast Guard. He enlisted because some of his buddies who also were police officers convinced him to sign up with them.

“I had two young sons then and they had started drafting men with two children,” he says. “The idea of the Army scared the hell out of me and the idea of the Navy made me seasick, so I joined the Coast Guard.”

He and his four friends were stationed together in New Orleans, where they worked in field intelligence. After leaving the Coast Guard in 1945, he returned to the Wichita Police Department. He eventually quit his police job, though, because he was fed up with what he called the laziness of some of the officers on the force.

Because of his work on the student newspaper and his work with the police department, Stone was hired as a reporter for The Wichita Eagle in 1947. Naturally, he started on the police beat, but also worked general assignment. “I always tried to stay on general assignment,” he says. “You got to do what you wanted to do, and, if you were any good, you got in on all the good stuff.”

The Wichita newspaper scene in the late 1940s was lively, he says, recalling head-to-head battles with Wichita Beacon reporters, trying to be the first to break big stories. “The Eagle was the kind of place where you hated to be assigned out of town for even a day for fear of missing something memorable that happened in the newsroom while you were gone,” Stone says. His memory about former police cases and newspaper stories is still crisp and clear.

One of the biggest stories he covered was the 1950 murder of Emporia banker Herbert Kindred near Peabody. He covered the initial story and beat The Beacon in getting an exclusive interview with the banker’s widow. The banker’s driver was arrested and stood trial, but was acquitted. “He had a clever lawyer,” Stone says, recalling not only the driver’s full name but also that of his attorney.

A former Eagle editor with whom Stone “didn’t always get along” lured Stone to San Diego in 1953 to work for The Evening Tribune, which paid $115 a week, $35 more than The Eagle. Stone worked at The Tribune 10 years before moving over to The San Diego Union, where he wrote until he retired in 1977 at age 64.

He covered big stories in California, too, including the student protests and riots against the Vietnam War and the deadly Watts Riots in Los Angeles in 1965.

Always the master of the quip, Stone and a photographer were warned by National Guardsmen of sniper fire from nearby roofs during the Watts Riots. They were told to “hit the deck” if they heard gunfire. “Would you mind falling on top of me?” Stone asked his colleague.

1967 screenplay for an episode of Gunsmoke that won older brother

Milburn an Emmy, worked not only as a journalist, but also as a police

officer and farmer.

He won numerous state and national writing and reporting awards while working for the San Diego papers, including the Harold Keen Award given annually by the Copley Newspapers for writing excellence.

When he and Catherine retired to Borrego Springs in the Sonoran Desert in Southern California, his friend Hal Steward put in a good word for him with the editor of the biweekly Borrego Sun. Soon, the editor, Judy Winter Meier, a native of Hoisington, Kan., had him writing a column.

Stone frequently reminisces about his growing-up days in Kansas in his column. Last summer, he confessed that he’d been telling folks he was 90 when he wasn’t.

“That is a lie,” he wrote. “Concerning my age, I must say this: I would not have lived nearly this long had I not quit smoking two packs of Springs cigarettes a day 30 years ago.”

When he did hit 90 in January, Stone wrote that there were other reasons he thought he might never reach that milestone. He was told at age 3 he was to die of pneumonia. At 11, a runaway horse nearly killed him. A year or so earlier, he foolishly grabbed a telephone line that, because of an accident, was down on a trolley line that was carrying enough direct current to do him in. A doctor who came to look at him, Stone recalls, said, “He’s dead.”

“I don’t believe I was,” Stone wrote. “My brother, 8 years old, saw to it I didn’t die.”

In his 12 years as a street cop in Wichita, he became involved in several situations that also could have been deadly. He disarmed a 16-year-old boy he found sleeping on a fire escape at a school on his beat. The boy drew a pistol. “He suffered a dislocated shoulder when I deprived him of the weapon,” Stone wrote.

“I’ve lived a wonderful life,” he says. “For several years, I participated in mankind’s most important endeavor: agriculture. I was a farm boy and a farm worker.” He adds, “I was a street cop and detective, the most satisfying work ever. I finally became a newspaper reporter, which I wanted to be all along.”

While reporting on The San Diego Union, Stone was prodded by older brother Milburn to write screenplays for Gunsmoke, the popular western series set in Dodge City that debuted in 1955 and aired for 20 years. He resisted at first, but reluctantly began taking his typewriter with him on weekend camping trips.

Most of the draft of “Baker’s Dozen,” one of three or four episodes that Stone wrote for the CBS series, was composed on his manual typewriter on the tailgate of his stationwagon at Mario Mountain Campground in the San Bernadino National Forest near Idyllwild, Calif.

That part finally won Milburn Stone, who died in 1980 after an acting career that included more than 100 movies, an Emmy for his portrayal of feisty Doc Adams. The show aired on Christmas night in 1967 and featured Doc, who — following a stagecoach holdup — delivered triplets to one of the passengers, and then had his hands full caring for them.

In a courtroom scene that followed, Doc came into conflict with the judge over the question of separating the triplets or sending them to an orphanage. Stone says he originally wrote the script because he wanted to create an hour-long western without violence. There wasn’t a single shot fired in the episode.

Milburn, who portrayed Doc on Gunsmoke in nearly 500 episodes, was rightfully proud of his younger brother when CBS produced Stone’s script. “Joe can write standing on his head,” Milburn once told a TV writer.

Stone has written often over the years about his singing ability. He once called himself “the finest boy soprano between Kansas City and Denver.” He says his mother, “a splendid alto,” was the greatest harmony singer he ever heard. “I could not read music,” he says. “She taught us how to hear the harmony — tenor, bass and baritone. And to sing it. It was called faking it.”

Stone, always a ham on stage, got his first taste of show business with brother Milburn, who left home as a teenager to act in a traveling repertory company that toured small towns and county fairs in Kansas, Nebraska and Colorado.

Perhaps the brothers were inspired by their uncle, well-known Broadway personality Fred Stone. “Six shows a week, move to the next town,” Stone recalls, “and do it over and over again.” Primarily a “go-fer” with the title of stage manager, Stone occasionally had bit parts. When the company’s format changed, he sang in the barbershop quartet. “Talking pictures” ended his theatrical and musical career, which lasted less than a year.

When Stone worked for the Wichita Police Department, he organized a barbershop quartet. An honorary life member of the Wichita chapter of the barbershop quartet society, Stone still sings in public. This past February, he returned to Borrego Springs to appear in his third straight songfest called “Borrego Sings.” He sang two solos, “Maggie Jones” and “I Wanna Drink My Java From an Old Tin Can When the Moon Is Riding High,” and serenaded his wife of six-plus decades with “You’re My Everything.”

“I still love to sing,” he says, “but nobody asks me anymore.” When the Elliott School of Communication honored him and other graduates at a reception the day of commencement, someone did ask him to sing. And he obliged, reeling off two quick ditties. Then, accompanied by one of his sons, he ended with the old University of Wichita fight song. “We’ve been working on that one,” he admits.

Dr. Susan Huxman, interim director of the Elliott School, says Stone’s many and varied accomplishments serve as an inspiration to younger students: “His many exciting newspaper jobs remind our students of the value of a communication degree, the importance of finishing what you have started — and maybe even that work in the communication industry is good for your health.”