Through community service projects, large and small, on the job and off, Shockers everywhere are working for the greater good. In their own distinctive ways, these three Wichita State graduates — Jerry Florence '71, Nissan Foundation, Los Angeles, Calif.; Arneatha Martin '75/80, Center for Health and Wellness, Wichita; and Jack Jonas '54/67, Cerebral Palsy Foundation of Kansas, Wichita — have made our world a better place.

Constructing a Dream

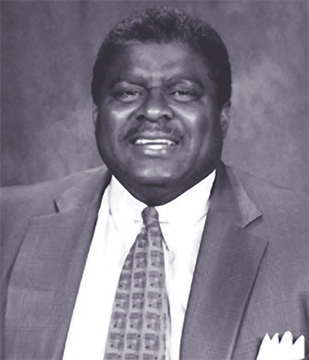

Arneatha Martin '75/80, co-president and CEO of Wichita's new Center for Health and Wellness, is talking about the vision that has shaped and defined her life for two decades.

Arneatha Martin '75/80, co-president and CEO of Wichita's new Center for Health and Wellness, is talking about the vision that has shaped and defined her life for two decades.

She suddenly says, with gentle vehemence, "For so many years, I was so irritated. The members of the Black Nurses Association — which I belong to — had to go all over the place to treat people. It was frustrating, and I remember thinking, 'What we need is a place!'"

After four years of planning and fund-raising, Martin finally has her place. The cetner opened July 20 at the corner of 21st Street and Erie in northeast Wichita. Already it's becoming the catalyst for change that she had envisioned. "People were standing in line to get in the first day," she recalls. "During the first week alone, we saw more than 90 patients."

Bud Gates, chairman of Wichita's Gates Enterprises and the center's co-president, has worked closely with Martin on the project. "I knew we'd succeed," he says, "because Arneatha doesn't know the meaning of the word 'no.' She will go over, under or around any obstacle once she has a goal in mind. She's like the Energizer Bunny!"

Martin's hands-on career in nursing, nursing education and mental health nursing provided her a thorough grounding in what was needed to improve health care for Wichita's chronically underserved population. And she learned why a healthy lifestyle is too often out of reach for too many people.

"Traditionally, just getting to the doctor is hard enought," she explains. "You have to take off work, proabably without pay. You have to find reliable transportation and some place to put your children. At your appointment you're told you have this or that and are sent on your way with a prescription or advice you more than likely can't follow. It's no wonder so many people don't seek medical help. They just hope the problem will go away. It doesn't."

Therefore, the Center for Health and Wellness isn't a "clinic" in the traditional sense. That's part of Martin's comprehensive plan for improving the quality of community residents' health through positive lifestyle changes. She envisioned a centralized state-of-the-art health care facility that would serve a variety of health care and lifestyle needs, function as a central catalyst for proactive health strategies and become a community center.

Martin says, "You can't just drop a building somewhere and say, 'OK, here it is. Use it.' It doesn't work. This center was designed to be different -- it's a part of the community. Our goal is for people to be as comfortable here as they are in their own homes, so they'll return."

The center's hours accommodate the schedules of working people with children — 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. Mondays through Fridays and 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. Sautrdays. The spacious windows of the waiting area look out on an enclosed play area furnished with new, brightly colored playground equipment. Inside, children of all ages can use two computers and printers to play games, create art or do homework. Downstairs is the staffed Children's Learning Center, which provides educational activities for various age groups, a large color video screen with health-related CD-ROMs, more computers and printers, books and lots of toys.

These amenities support one of Martin's critical goals — to make the center appealing to children. She believes educating children to make healthy choices early on will prevent a lot of illness in the future.

She recalls how one little boy, visiting the center with his parents, saw the computers and said he needed one to get extra credit in his school work. "I told him to come in any time and use the computer. His grades were good, but he wanted to do better. And that's what this place is all about!"

Empowerment thus takes many forms, large and small. It occurs when people learn how to manage their health. It fosters self-esteem, a crucial component of the wellness concept. Martin points out, "Empowerment creates self-esteem. For example, our patients have to pay for services in some way, whether it's money or insurance or volunteering to paint us a picture, mow the grass or supervise the children. This isn't a charity operation — it's a partnership with the community." The northeast community has bought into that partnership in a big way. Of the $2.1 million in contributions the center has received to date, $87,000 has been from area residents.

Martin's job isn't finished. Far from it. She views the center as a work in progress, and her next goal is to fund an endowment to cover any unforeseen operating losses. Moreover, she discovered while planning the center that there's nothing like it anywhere else in the country — and she envisions the center's concept of health care spreading to communities nationwide.

With a smile of determination, she says, "Why not? Restraints prevail only if you let them."

— By Kat Schneider '72

Moving with the Spirit

The work Jerry Florence '71 does as president of the Nissan Foundation for Nissan North America was put in perspective when a participant in a Nissan-funded initiative approached him.

"Mr. Florence," the young man said, "a year ago I didn't know where I was going. I would probably be dead today, and definitely wouldn't be here, if not for this program."

"Mr. Florence," the young man said, "a year ago I didn't know where I was going. I would probably be dead today, and definitely wouldn't be here, if not for this program."

The student was referring to the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz, a nonprofit organization that offers intensive college-level training with the jazz masters to the world's most promising young jazz artists. Florence had just attended a concert at which the young man had performed. The student's words reminded him of the bedrock reason he works so thoroughly to insure that Nissan's funding makes the greatest difference it can: his belief in the human spirit.

Florence brings a unique perspective to his role as head of the Japanese car-maker Nissan's charitable arm. His bachelor's degree is in chemistry, and he spent his time in the trenches, establishing several patents for rendering wiring less of a fire hazard when he worked at General Electric. He joined Nissan's national headquarters in Los Angeles as vice president for marketing in 1993 and soon moved to vice president ofr communications and strategic development. This year, he landed the prestigious Foundation presidency because of his expertise in what he calls "relationship marketing." The position was created to help change Nissan's image, to "Americanize" it, in his words.

"We lacked an identity in the marketplace. People couldn't tell you what Nissan stood for," Florence says. His role is to help determine and then publicize the community-service commitments the company makes.

Nissan focuses many of its philanthropic efforts on rebuilding south-central Los Angeles, which was torn apart by civil unrest in 1992. One such Nissan-sponsored undertaking is the Amer-I-Can Nissan Stop the Violence program, which mobilizes young people often destined for gangs to bond together to clean up south-central LA.

"Nissan is committed to good corporate citizenship and giving back to the communities it does business in," Florence says.

Among other beneficiaries of Nissan's philanthropy is the Nissan/Educational Testing Services Historically Black Colleges and Universities Summer Institute. While being interviewed for this story, Florence was in Tallahassee, Fla., helping coordinate the institute's offerings to minority higher education institutions. This year, school administrators focused on leadership issues.

Nissan's support of the institute is an example of the company's drive to attach its name to "feel good" projects. Florence's marketing background is crucial in such efforts. "I believe in the marketing function and ideology more than just philanthropy," he says.

In the past, industries donated to a cause with few, if any, expectations for return benefits. Now, many corporations stipulate that their support must bring value to them. "It can create a win-win situation," Florence says. "But you've got to work hard sometimes to get to that point."

Take for instance one of his mmost successful ventures, the Earth2U: Exploring Geography program, of which Nissan is the exclusive national corporate sponsor. Earth2U is an interactive, traveling museum devoted to helping increase children's knowledge of geography. The fact that the progam is a joint effort with the National Geographic Society and the Smithsonian Institute isn't coincidence — they're two "all-American" entities that help bolster Nissan's national identity.

When Earth2U was presented to Nissan, the proposal was for a five-years, $1 million commitment. When Florence and his crew were finished enhancing it, Earth2U was guaranteed to reach 10 million kids nationwide, complete with CD-ROMs and a $10,000 gift to every museum, science center and educational institution that books the show.

"We don't expect to sell cars through Earth2U," Florence says. "We do want to give the brand exposure and build goodwill. Besides, it's the right thing to do for our children's education."

The project stemmed from a study commissioned by National Geographic to test children's proficiency in geography, in which U.S. students scored last of all the industrialized nations.

"Dead last," Florence emphasizes. "Given the chances that our kids will work, travel and communicate with poepole outside of the U.S., that's a serious shortcoming. One that Nissan wants to help National Geographic and the Smithsonian correct."

Nissan's involvement with the Los Angeles Urban League is another example of "relationship marketing." While Nissan funds Urban League projects, the organization provides valuable market research for the automobile company and helps improve the minority supplier base and increase the number of minority Nissan dealerships.

Florence is excited about being named chairman of the board of the Infiniti Fund for Brain Cancer Research at the Johnson Cancer Research Center at UCLA. Current research involves genetically mapping genes, which brings Florence back to his old chemistry days. "This is tangible research," he says. "If we're successful, many Americans — in fact, many people all over the world — can be saved."

It's no accident that many of Florence's community-service projects involve helping younsters, often those from the inner city. "Anything dealing with young lives, that can turn them around, gives me the juice to go on," he says. He often thinks of his son, Michael, who is 12, when he meets the kids whose lives are improved through these efforts. "He is a big reason I do all of this stuff. He has a responsibility to make the world better, and I hope I can teach him how to do that."

Florence also credits his wife and high school sweetheart, Winifred (Watson) '71, for supporting him during his hectic travel and work schedule. Because they both have relatives in Wichita, they're in town at least once a year. Often, Jerry times his family visits with meetings of the WSU Endowment Association's National Advisory Council, on which he serves.

He returned to campus last May to receive the prestigious WSU President's Medal, an honor bestowed only upon those individuals who have demonstrated "extraordinary and exemplary leadership through integrity, service to humanity and expertise in his field."

As part of his acceptance of the award, Florence delivered the 1998 commencement address. He encouraged graduates to discover their dreams and pursue them, but added, in true Florence style, "The real value of your life is not what you achieve, but how you achieve it."

Never forgetting the family that raised him to believe in himself, he also quoted his grandfather, the Rev. J.W. Washinton, "a very wise man who knew how to boil life's problems down to their essence." Florence recalled that whenever he asked for advice about a difficult decision, his grandfather would say, "Do good, and forget about the rest."

So it has been with Florence's own community-service work. He certainly spoke from experience when he told the graduates: "Do good, commit to excellence, develop your character and love your fellow man. Forget about whether it's the information age or the stone age. You will thrive. You will prosper. And you will be worthy of honor."

— By Lynette Murphy

Expanding the Vision

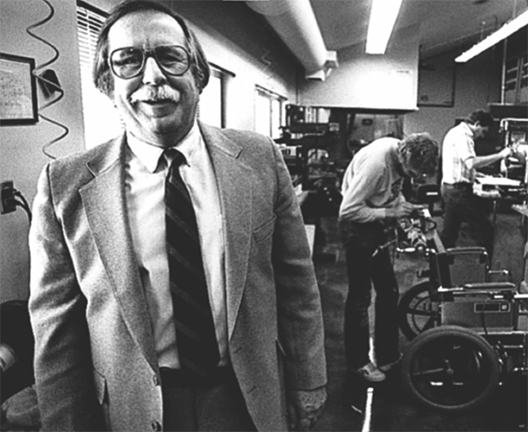

It's been 25 years since John F. "Jack" Jonas Jr. '54/67 founded the Wichita-based Cerebral Palsy Research Foundation of Kansas and 10 years since he received the WSU Alumni Association's Achievement Award for that organization's trail-blazing efforts on behalf of the physically disabled. But accolades are beside the point to this energetic, quiet-spoken man. He's more interested in continuing to find ways to improve the quality of life for individuals.

Jonas embodies a rare combination of talents. Dan Carney, who's been chairman of CPRFK's board of directors since its inception, remarks, "Jack is a businessman and a humanitarian. He's organized, practical and idealistic. His ability to synthesize those traits and translate them into successful action is remarkable."

Jonas embodies a rare combination of talents. Dan Carney, who's been chairman of CPRFK's board of directors since its inception, remarks, "Jack is a businessman and a humanitarian. He's organized, practical and idealistic. His ability to synthesize those traits and translate them into successful action is remarkable."

In those 25 years, CPRFK has become a $16 million company that addresses virtually all of the challenges facing the physically disabled. Currently its projects include research in cooperation with the National Rehabilitation Engineering Institute for Productivity at Wichita State University and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; applied research at the Daniel M. Carney Rehabilitation Engineering Center; The Timbers, a 100-unit residential housing complex for the physically disabled; and Center Industries Corporation, a financially self-sustaining enterprise that employs the physically disabled.

All of this happened, Jonas insists, because he understood one thing: "The trick is to figure out what you youself don't know and then go out and find the people who do know. I was extremely fortunate in that regard."

Jonas realized early on that "employment with dignity," as he terms it, is the key to independent and self-directed life-syles for the physcally challenged, and in 1975 he founded Center Industries to provide exactly that kind of work. Work that was meaningful. Work that paid well. Work with benefits and a retirement plan. Work that enabled people to live where they wanted to live, save for a vacation, pursue a hobby and enjoy life. He explains, "I intended for Center Industries to emulate 'real world' or ongoing industry as closely as possible. I didn't want a 'tin cup' operation. If we were going to succeed in manufacturing sophisticated products, we had to be able to convince Cessna, for example, to use us. That would have been more difficult if CIC had been perceived as a 'sheltered' workshop."

That vision entailed risk. It meant that CIC had to elicit a high level of workmanship from its employees in order to compete for contracts in the private and governmental sectors. "It doesn't matter how lofty or exemplary your motives are," Jonas says. "If you can't produce a quality product on time at a competitive price, you're not going to be in business very long."

Today CIC competes with the best — and wins. CIC is the sole supplier of the M-16 rifle clip for the U.S. government, turning out some 50,000 clips a month to met a multimillion dollar contract. It is the sole manufacturer of the windows and window fames for Boeing's 727,737, 747 and 777 aircraft. CIC manufactures the engine mounts for the Cessna Citation airplane and the flap tracks for all Raytheon aircraft. CIC employees also supply transmission parts for the John Deere Company and manufacture Kansas auto license plates and validation stickers. "The tags sound like an easy product to make, compared to an engine mount," Jonas comments with a smile. "But we have to meet the standards of the Department of Revenue and please 105 county treasurers!"

CIC employs more than 175 people, of which 75 percent are physically disabled. Jonas says, "No other program in this country employs the physically challenged at such an advanced namufacturing level." In addition, he has been able to direct fudning to other CPRFK activities from CIC's profits.

In the past few years, CPRFK has completed a $2 million renovation of The Timbers and has begun several new projects, including a day-care program for the physically challenged and a rehabilitation program in closed-head injury.

According to Carney, "Jack pioneered the concept and practice of social entrepreneurship, and he undersands that CPRFK, like any business venture — no matter how humanitarian it is — must grow and change in response to evolving needs if it is going to remain successful."

To that end, Jonas has made it a point to bring young business talent to CPRFK's board of directors. Two of his sons have bought into his vision and work for CPRFK; Peter is in sales at CIC and Pat is the chief operating officer of CPRFK.

And Jonas has set up a 15-member board of entrepreneurs to act in an advisory capacity to CPRFK. Jonas chuckles. "These are young people with young ideas," he says, "and that's good. Our board of directors charged them with developing a five-year plan and an overall strategic plan, and then we sat back and let 'em go at it."

Jonas also has recently realized a very personal goal. After his first wife, Eileen, died of breast cancer 10 years ago, he and her oncologist, Dr. Paik Nyon Kim, established the Midwest Cancer Foundation to support early breast cancer detection. The foundation developed a mobile state-of-th-art mammography unit that travels to sites statewide. Jonas remarks, "Early detection is crucial to a successful outcome. Statistics from this unit indicate that, of 18,000 women screened, 1,700 had "suspicious" readings, and 79 were "positive." If just one of these women is cured because of early detection — and I'm sure there'll be more than that — this project has been worth it."

The foundation recently turned the operation of the mobile unit over to the Via Chrisi Regional Medical Center, and, Jonas adds, "Via Christi has said they're going to field another unit as well. That's wonderful news!"

Although he admits he wants to relax a ittle more these days, Jack Jonas continues to find new ways to enhance people's lives. He says, "I'm in this for the long haul — whatever it takes!"

— By Kat Schneider '72