nine-story building in the center of Shostka, Ukraine, where they

teach communicative English.

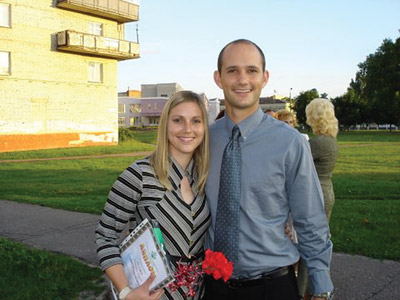

Stephanie Whitcomb and Matt Clark had a lot in common as athletes at Wichita State University.

Both were known as team players. Whitcomb, who hails from Moundridge, Kan., was the first four-year player in the Chris Lamb volleyball era.

Clark, from Fort Collins, Colo., was the first four-year player in Mark Turgeon’s stint as men’s basketball coach. Both were on the athletic director’s honor roll every semester. They helped lay the foundation for the future success of their Shocker teams.

Their similarities didn’t end on the Shocker courts. Both graduated in May 2004. Neither was sure what they wanted to do with their lives, but both had a desire to travel, experience other cultures and serve others.

It was Matt’s idea to enlist in the Peace Corps. His first exposure to the volunteer organization came during his physics class his junior year in high school. He says he was an awful physics student. But he enjoyed the energy of his teacher, who one day brought slides of his experiences serving in the Peace Corps in Africa. Matt can’t recall the country in Africa, but he saw an opportunity to travel the world, basically free. He stored the idea in the back of his mind, forgetting about it until he finished college.

After graduation, Matt moved back to Colorado, as did Stephanie. During that time, they talked often about the possibility of joining the Peace Corps. The two former athletes talked to some former Peace Corps volunteers, who raved about their experiences. That encouraged them to do some additional research on the organization.

Before long, their plans were made: They would get married and then apply to join the Peace Corps together. It seemed like a perfect fit. They started dating the spring of their junior year at WSU. Matt proposed in February 2005, and they married in a backyard ceremony that summer at Stephanie’s parents’ home in Moundridge. They waited 11 months before they accepted an invitation to head for a new adventure.

Matt and Stephanie are living in Shostka, Ukraine, a city of about 85,000 about an hour from the Russian border. Both are teachers. They lived and trained in Uzyn, which has a population of 10,000, for three months before moving to Shostka. They had intensive language classes, cultural training (learning customs, traditions, behavior, etc.) and preparation for teaching. In some ways, they recalled, coming to their new home was similar to college recruiting trips. The community welcomed them.

Stephanie, a communication major with an emphasis in broadcasting at WSU, is teaching communicative English to fifth- through 11th-graders. Her school, called a lyceum, is advanced with English, but the focus is on math and science.

Matt, an English graduate, teaches in a gymnasium — which unfortunately, he says, has nothing to do with athletics. It’s a school that emphasizes arts and languages. He has students in grades eight through 11, also teaching primarily communicative English. With older levels, however, he has started studies on other countries — America, Canada and the United Kingdom.

The Ukrainian education system is much more rigorous than in America, both say. School days are long and include Saturdays. Initially, Matt and Stephanie were intimidated by their students’ abilities. Their challenge was to find ways to keep them engaged with the English language, not teaching them the alphabet, like they naively thought. Stephanie soon decided she could throw away the children’s books focusing on letter sounds that she brought with her.

For her, the interaction with students and teachers is the best part. “I love getting to know them and seeing the similarities and differences between them and Americans,” she says. The part she dislikes is planning for classes.

Matt’s principal, with the help of the city’s mayor, helped them find housing. They have an apartment on the top floor of a nine-story building in the center of town. They can see a massive statue of Lenin out their window.

Shostka has a fireworks factory, so they often hear and see fireworks during concerts, weddings and holiday celebrations. Everything they need is within walking distance, they say, including their schools.

The city turns off the water each night from 11 until 5:30 or 6 the next morning. “It’s a mad scramble when we realize we only have a few minutes of water left to finish the laundry or the dishes or take a bath or brush our teeth,” Stephanie says.

They clean house, do laundry (by hand, of course), cook and eat most every meal together. They rarely eat out — only when they go to Kiev — so they spend a lot of time learning how to make and create new meals.

Stephanie initially thought going to a foreign country would mean getting to wear her hair in a ponytail every day with a pair of jeans, T-shirt and flip-flops. Instead, she discovered that appearance is important in the Ukraine. Surprisingly, she says, she’s learned to like it: “Every day, I get to leave the house dressed up in their fashionable clothes, with my hair and makeup done. It makes me feel good about myself.” Back at home, however, it’s quickly back to sweatpants and her favorite Shocker volleyball T-shirt.

When they return to the United States, both would like to continue their education. But they’re not sure in what subject area and where. They have access to the Internet, so they can research graduate schools and careers. Still, they haven’t made any decisions. Their 27-month commitment to the Peace Corps ends in December 2008. Both stress, however, that they want to be near their families if possible when they return to the States. Both say that’s what they miss the most.

Stephanie comes from a close family. Her parents seldom missed one of her volleyball games in high school and college, even when the Shockers played on the road. She still talks to them weekly, but says it’s not the same as seeing them in person. After family, Matt says he misses the recreational opportunities. “Almost every school in America has a gym, tennis courts, football field, soccer field, baseball diamond, weight room, etc.,” he says. “Shostka has one basketball court that you won’t severely injure yourself on. Try to avoid the right wing on the north end, and never dribble there.”

The soccer field where he plays four or five times a week is made of dirt and gravel, complete with mature oak trees and metal posts that he occasionally uses for protection during games with real soccer players. The tennis court isn’t finished yet, he says, and if maintenance is any indication, it won’t be ready until 2010. “I will never take parks, athletic facilities, museums, libraries, bike paths, campgrounds or hiking trails for granted — ever,” Matt says, adding that he also misses ESPN, the Shockers and washing machines. Stephanie says care packages and gifts that family and friends send help them not be so homesick. But she admits she could go for some Starbucks, or a late-night run to Taco John’s, Wendy’s or Spangles.

Matt says he can’t think of what he misses the least about home. Surprisingly, he says, the Peace Corps experience has made him more patriotic. “We came here hoping to learn about a new culture and experience a new approach to life,” he says, “and we have certainly done that and will continue to do that. But people will always view foreign countries through past experiences of their native land.

“Pretend ideas are clothes. Each time I see something I like or dislike in Ukraine, somewhere in the back of my mind I’m trying it out in America. Would America look nice in this? Could this fit? I love America, and this experience makes me want to help it continue to grow and improve in whichever facet I am able.”