The seaward flash was expected. The level of destruction was not. After the Israeli bombing of Beirut began with a strike at the city’s main airport on July 13, a Thursday, and continued with hits to roads, bridges and fuel depots, Janine Youssef, her family and extended family gathered on the balcony of their apartment.

“We could see the airport from our apartment, watched all the bombs come from the sea and air. The destruction was unimaginable. The whole neighborhood where my mother-in-law lived was wiped out. Thousands of people lost everything, many dead. There was no way for us to go anywhere. All the bridges were destroyed. There was no way out.”

War was new to Janine Youssef ’91 — wife, mother of three, violinist with the Lebanese National Symphony Orchestra and instructor at Lebanon’s national conservatory.

To many others in Beirut, war is anything but novel.

“Thursday morning the airport was bombed,” Youssef recalls. “The bombing of Beirut began that night. My husband’s family has experience with this, so we all knew that most of the bombing would be at night. We were all expecting and watching. The whole family was together, and we saw the flash of light from the sea and then the explosion of the targeted area.

“My main feeling was dismay, and frustration, but mostly dismay. I knew completely that we would have to leave, and it was like watching my life slowly unravel, with nothing I could do about it — especially after the attacks kept going on and on.”

Originally from Pueblo, Colo., the Wichita State graduate had moved to the seaport capitol of Lebanon some two years ago with her husband, Youssef Youssef, and their two sons, Ibrahim, now 13, Shadi, 9, and their youngest, daughter Zayna, 7.

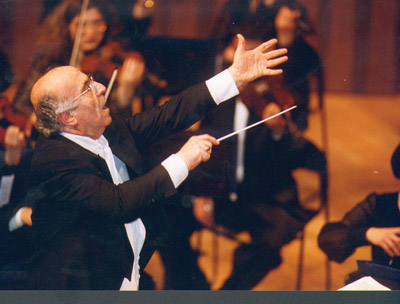

Last year, Youssef had been pleasantly surprised to meet a fellow Shocker, Walid Gholmieh, during the process of auditioning for the symphony orchestra and applying to teach at the conservatory. Gholmieh is one of Lebanon’s best-known composers and president of the Lebanese National Higher Conservatory of Music, which is home to both the symphony orchestra and the Lebanese National Orchestra for Oriental Arabic Music. He serves as chief conductor for both orchestras.

Gholmieh recalls, “A woman came to the conservatory and applied for teaching violin. The application was transferred to me, and a thrill covered me when I read that she is a graduate of WSU. I met Mrs. Youssef, and we had a conversation. I asked about Jay Decker, J.C. Combs, Walter Mays, James Riley, Howard Ellis and Gordon Terwilliger.”

WSU professor of music J.C. Combs explains that Gholmieh, who was born in Lebanon, visited Wichita State’s campus more than two decades ago to “share his music and experience with our students.”

Gholmieh had studied at Lebanon’s national conservatory and then studied mathematics at the American University of Beirut before devoting himself to music — and before Lebanon’s brutal civil war broke out in 1975.

For most of the 15-year war, Beirut was divided between the largely Muslim west part and the Christian east.

The central area, the site of so much of the city’s commercial and cultural life, became a no-man’s-land. Over the course of the war, tens of thousands of Lebanese citizens died, while hundreds of thousands more fled to other countries.

Unable to perform in Lebanon during the war, Gholmieh spent much of his time in Europe and the United States. With family in Wichita, he visited WSU on more than one occasion as guest conductor and lecturer. “I cannot forget the warmth of the community of Wichita, as well as the peaceful attitude,” he relates. “For WSU I remember values, care and endeavoring. I may say that the majority of my family, close family, live in Kansas or Oklahoma or Texas, but specifically in Wichita, and consequently generation after generation are WSU graduates.”

Gholmieh returned to his native land before the war’s official end in 1990 to take up directorship duties at the national conservatory, the heart of Lebanon’s classical music world. He inherited a burnt-out building, five pianos, 48 students and 36 professors.

From this nucleus, he rebuilt the conservatory, which has physically grown to comprise multiple branches and academically expanded to offer instruction by more than 200 teachers to some 4,800 students in classical and Eastern instrumental and vocal music.

This past concert season, which traditionally runs from September to June, the conservatory’s Oriental Arabic music orchestra boasted 50 performers, while its symphony orchestra comprised 100 musicians, including Youssef, who had begun playing violin with the orchestra in January 2005.

president of the Lebanese National Higher Conservatory of Music.

Gholmieh counts the renaissance of the conservatory as one of his most gratifying accomplishments. Composition is another.

The noted Lebanese music critic Nizar Mruweh, who died in 1992, listed Gholmieh as his second favorite composer of Lebanese Arabic music and wrote in detail about Gholmieh’s symphonies, including Al-Qadisiyyah (The Green Train) and Al-Mutanabbi (the name of a classical Arab poet).

“When I teach, I feel that I am a preacher of ideals. When I conduct, I feel that I am a philosopher. But when I compose,” Gholmieh says, “I feel that all the joy of life is mine.”

Gholmieh’s passion for music was evident to Youssef from the very first. “He is such a dynamic personality,” she says, adding that he is the energizing force behind all of the conservatory’s many endeavors.

Youssef’s own professional pursuits revolved around the violin. After earning a bachelor’s degree in music performance at Wichita State, she primarily focused on family. Her husband was a well-known baker, chef and restaurateur in Wichita, while Janine did freelance work and later began graduate studies in speech pathology at Wichita State.

But after moving to Beirut and settling her children into a new life close to their paternal grandparents and two sets of aunts, uncles and cousins, she was again making time for her music career. “I was enjoying teaching and playing violin,” she relates. “My mother-in-law, Sikna, and sisters-in-law, Nisrene, Samia and Mariam, were very supportive. We lived in the same apartment building with Samia and her family. We were all very close.”

Things were going well for her family in Beirut, Youssef reports, despite a few unaccustomed inconveniences, such as off-again, on-again electricity and “disorganized” traffic that made it an adventure to drive in the city. Much more important, her children had adapted well, were learning languages and getting to know their cousins, and her husband had opened a bakery.

Then Hezbollah militants began firing Katyusha rockets and mortars at Israeli military positions and border villages to divert attention from another Hezbollah unit that crossed into Israel on July 12, killed three Israeli soldiers and kidnapped two others in an attempt to negotiate a prisoner exchange. Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert called the incident “an act of war,” and Israel responded with massive airstrikes and a ground invasion of southern Lebanon.

The next day Israel announced an air and sea blockade of Lebanon, while continuing strikes in southern Lebanon and bombing the runway at Beirut’s main airport, forcing its closure. Hezbollah responded with rocket attacks targeting northern Israeli cities. In public pronouncements, the United States supported Israel’s right to defend itself from attack, while France, Russia and the European Union were critical of a “disproportionate” use of force.

That night the Youssefs and members of their extended family — Sikna and Mohammad Youssef; Nisrene and Abbas Awada and their one-year old son Ahmad; Samia and Ahmad Harkouss and their two sons Ali and Rayan; and Mona and Ali ’82/85/95 Youssef and their daughters Leila and Malak, of Wichita, who were visiting for the summer — came together to watch, as Janine describes it, “the bombs come from the sea and air.”

On July 14, the crisis only deepened after the Beirut offices of Hassan Nasrallah were bombed, prompting the Hezbollah leader to call for “open war” against Israel. As Israel continued its airstrikes and artillery fire on Lebanese civilian infrastructure, including roads and bridges in and near Beirut, the senior Youssefs’ home was destroyed and Youssef’s bakery — open for business a mere 40 days — was damaged beyond repair.

Lacking any reasonable alternative and not knowing how long the conflict would last, the Youssefs began making plans to leave. Thousands had already fled, with the international community stepping in to assist in the evacuation of foreigners.

“We waited a week,” Janine Youssef reports, “and then we arranged for a van to take us to Syria. My husband’s brother Ali and his family left later and made it out through Turkey. We left with my husband’s mother and father, his sisters Nisrene and Samia and their families and another Lebanese woman and her two boys who were stranded in Beirut. We were ready to run — the kids were in their tennies and T-shirts. We were numb by then.”

Orchestra and instructor at Lebanon's national conservatory during

the time she lived in Beirut.

After the seventh day of hostilities and as the Youssefs were carefully and nervously wending their way to Damascus, Lebanese Prime Minister Fouad Saniora appealed for an end to the Israeli attacks on his country, saying that more than 300 people had been killed in air raids to date, with an estimated 1,000 Lebanese wounded and 500,000 displaced. The Israeli death toll stood at 25. “My heart is heavy, especially about the number of children killed,” Youssef says.

After the four families arrived safely in Damascus, they each went their separate ways. “It was such a sad thing, saying goodbye to everyone,” Youssef says and explains that she and members of her immediate family then flew out of Damascus to Budapest to New York City and then drove to Wichita.

The Israel-Lebanon conflict, known in Lebanon as the July War and in Israel as the Second Lebanon War, came to an end when a United Nations-brokered ceasefire went into effect Aug. 14. More than 1,500 people, many of whom were Lebanese civilians, were killed in the conflict. Some 900,000 Lebanese and 300,000 Israelis were displaced. For many other individuals in Lebanon and Israel and countries farther afield, normal life was another casualty of the war.

For Gholmieh, his attentions remain fixed on the conservatory and its musicians and students. “I never thought of leaving Lebanon,” he reports. “No destruction befell the conservatory since the bombing was far from the locations of all the conservatory branches all over Lebanon. Most orchestra members of both the symphony and the Oriental Arabic are back, and we re-maintained rehearsals since September 11. We had one performance with the Oriental Arabic orchestra on September 29, and we are having a concert with the symphony orchestra on October 6.”

Youssef misses playing with the orchestra, misses teaching violin at the conservatory, misses her in-laws and the family routines they created together. But she is resolved to making the best for her family, wherever they call home.

Her kids, she says, are troubled by the destruction they saw. They miss their cousins and friends, but are resilient and comfortable attending Wichita private schools. Her husband is exploring business opportunities, and she is looking into taking on private violin students.

“Mrs. Youssef was and is respected by all the faculty members, students, administrative staff at the conservatory,” Gholmieh reports. “I’ve sent an e-mail to her informing her that she is always welcome whenever she thinks to come back to Lebanon.”

A faraway look veils the natural glint in her eyes when asked if she would like to return to Beirut. The glint is back when she answers: “Maybe in the spring.”