Alabama, works with Potters For Peace. The organization

has championed a worldwide water-filter project that

employs a low-tech, low-cost burner that he began

designing while a WSU grad student in ceramics.

W. Lowell Baker ’71 makes an international adventure of his career as a ceramics teacher. He is involved with Potters For Peace, an organization with a mission of teaching potters and others in Third World countries how to make ceramic water filters that produce safe drinking water.

Every day, some 5,000 children die from the effects of drinking unsanitary water. According to the PFP website (www.pottersforpeace.org), diseases related to inadequate water and sanitation cause an estimated 80 percent of all sickness in the developing world.

“The infant mortality rates in these countries are terrible,” Baker relates, “and so much of that is due to impure water.” The low-technology, low-cost ceramic water purifiers, or cwps, developed by PFP are playing a key role in alleviating this dire reality.

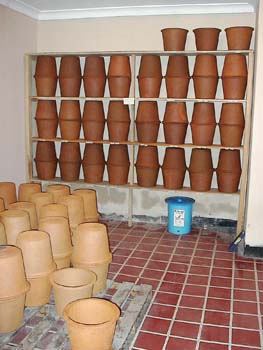

Baker and other PFP members teach potters in developing countries how to create the filters out of a mixture of local terra-cotta clay mixed with sawdust or another combustible, which burns away in the firing process, leaving a network of fine pores. The cooled ceramic piece is coated in colloidal silver. The bactericidal properties of the colloidal silver combined with the fine pores result in filters that are effective at eliminating 99 percent of water-borne diseases, including E. coli and Streptococcus organisms, according to studies done by MIT, UNICEF and the University of Colorado.

The ceramic filter is placed in a five-gallon plastic or ceramic container with a faucet and a tightly closing lid. Water is purified at a rate of one to three liters per hour. Baker explains that the most expensive ceramic water purifiers in Guatemala cost $35 each, and one CWP unit can provide a family with clean, safe drinking water for two years. Local potters can create the simple pressed bucket-shape filters, providing a community with industry as well as potable water.

Baker was contacted in 1991 by PFP for help in using a sawdust burner he designed. While a graduate student at WSU, Baker began work on a burner to fuel ceramic and brick kilns using alternative fuel sources. He had come to WSU to pursue a master’s degree after first graduating from high school in Enid, Okla., and then receiving a bachelor’s degree in fine arts from Phillips University in Oklahoma. Years after Baker’s creation, PFP used his burner design in Nicaragua to burn coffee hulls.

“My major contribution to Potters For Peace, besides minor kiln design input, is the burner,” says Baker, who earned his Master of Fine Arts in sculpture and ceramics at Wichita State and is now a professor of art in ceramics at the University of Alabama. There, he is working with colleagues to design a burner that does not require electric motors.

It will be human-powered, by bicycle. This low-tech burner would benefit people in countries with scant resources and rural areas where conventional energy — or access to motors — is not readily available.

To date, the PFP water-filter project has helped rural populations in Nicaragua, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Cambodia, Bangladesh, Ghana, El Salvador, the Darfur region of Sudan, Myanmar (Burma), among others. Baker himself has made trips to Nicaragua and Guatemala to teach the filter-making process.

simplest presses use a hand-operated

hydraulic truck jack and a two-piece

aluminum mold to make the bucket shape.

In addition to his travels for PFP, Baker has visited various Asian and South and Central American countries on other art endeavors. As often as possible, he takes his wife and his 18-year-old son with him: “Whenever I find out I’m going somewhere, we see if we can fit it into their schedules.” Outside of the United States, Baker and his family have trekked to Guatemala, Singapore, Japan and Hong Kong together.

This past September, but sans family, Baker visited Havana, Cuba, to work with the Instituto Superior de Arte, the only school in the country to grant Master of Fine Arts degrees, on developing an exchange program with the University of Alabama.

“I’ve traveled a great deal in Central and South America, and I’ve found that any time you go someplace, meet the people, live with them, discuss your discipline with them, you’re going to be better off,” Baker says. He adds that American students who participate in the exchange program are sure to reap many benefits while studying under the tutelage of Cuba’s leading art instructors and being immersed in a culture geographically near ours, but far from it in customs and philosophies.

Although American faculty and students will be able to spend time studying or teaching at ISA, the Cuban government remains unwilling to allow its citizens to travel to the United States, Baker reports — making the “exchange” program somewhat of a misnomer.

Nonetheless, Baker is sold on the concept of international exchanges. No matter where students study outside their home country, no matter what discipline they are there to study, the chief advantage is that they have the opportunity, as Baker explains it, “to learn how the other half lives, how they do things.”

It’s no surprise this artist, educator and world traveler has yet another trip on the burner — a return visit to Cuba for an international symposium of ceramic artists this December.