more than a decade, teaching at the National Art

School and showing his art works around the world.

Andrew A. Totman ’86 has become adept at capturing the elusive forms of his imagination and memory. That these private figures resonate with viewers from Latin America to China, Europe and across the United States – well, that’s the touch of art.

“Andy’s works always seem to be playful,” says John Boyd, a lauded printmaker and WSU art professor. “They have a broad appeal.”

Their appeal may become broader still this coming December when Totman shows his work at the Two Lines Gallery in Beijing. In an e-mail note sent from his home in Sydney, Australia, he explains, “The works in the China show will be large-scale monoprints, etchings and drawings.”

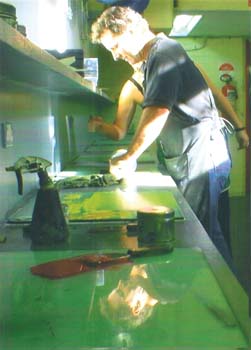

A California native, Totman became interested in art early. He enrolled at the University of San Diego as a printmaking major, earning his bachelor’s degree in 1983. While a student there, he learned about Boyd and his work at Wichita State – which lured Totman to graduate studies at WSU and, he says, “many long nights in the print room.”

After grad school, he served for a time as assistant curator at WSU’s Ulrich Museum of Art and participated in the Consultant Artists-in-Residence program at the Centre d’Art Contemporain Chateau Beychevelle in Bordeaux, France, before working as an assistant professor of art at the University of Alaska in Anchorage and then as an assistant professor of art in the Artsreach program at the University of California, Los Angeles.

In 1997, he moved to Sydney, where he is today a printmaking lecturer at the National Art School. As he shared with a group of students when he returned to WSU’s campus this April to teach a workshop and classes, the National Art School has a long and fascinating history.

The school’s origin dates back to 1859, and, in 1921, after the Old Darlinghurst Gaol had been converted, the school took up residence within its vast sandstone walls.

range from vibrantly colored

figures, such as "I Have No

More For You" above, to

images pulled from a single

inking of black.

“This is where I go to work,” Totman relates as he shows a slide of the school before moving on to slides of his own printmaking works, which range from the large-scale to series of etchings rarely larger than eight inches square.

Totman returned to Wichita State at the invitation of Boyd. “Art is a difficult area to have success in,” Boyd says. “Andy has chiseled out a place for himself through hard work, perseverance, talent – he’s put it all together. Personally, I’m real proud of him.”

etching with color

relief roll, 20x15, 2005.

Totman, who hadn’t been on campus for some 20 years, enjoyed his visit.

“I had so many memories and have lived in so many different places that I wasn’t sure if some got mixed up with other locations,” he says. “I really loved being back. The university looks great! And the fine arts department still feels like home. The people were always the best part about my time at WSU, and that is still the same today. The time spent with Professor Boyd was just as if it was 20 years ago, and the time giving critiques to students let me give a little back to the program.”

Critiques of Totman’s style of work often mention his playful repetitions of familiar figures – ladders, houses, hands, for instance – and tie his abstracted forms, which are often set in vibrant fields of color, to the New Figurative movement.

drawing on pine, 36x36, 2006.

According to one critique posted online after a three-artist exhibition at a Stanford University gallery, Totman’s “images tell of his journey through German Expressionism and French Symbolism tinged by an undeniable West Coast Pop Art flair. The elemental figures represent the human soul in its daily metamorphosis.”

Totman himself simply reports that his works “are changing always. The art is becoming more abstract and the color has become more refined.”

One of the things Totman did while back at Wichita State was renew his acquaintance with the pieces of art in the university’s outdoor sculpture collection. He reports that he often talks about these sculptures in art lectures.

“It was a beautiful time to walk around the campus and see the old works and the new,” he says. “It was just after a soft snow fall.”