Wichita State honored Gordon Parks in 1991 with the President's Medal, the highest award given by the university for extraordinary achievement. During a luncheon in his honor following presentation of the medal, Parks was asked what he'd like to have engraved on his tombstone. "I don't expect to have an epitaph," he answered. "I expect to be around forever."

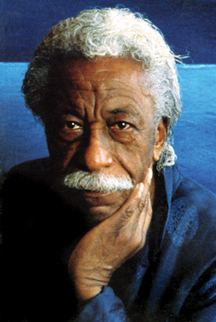

Now at the age of 86, Parks can't help but quicken his efforts in heed of death's inevitable approach. He often works late hours into the night, setting down his creative thoughts, searching out new forms for his artistic urgings, adding steadily to a body of work that encompasses tragedy and beauty.

"A blustery sky, a crescent moon or the blazing sun can hurry me to poetry or the camera," he writes in his most recent book. "When the doors of promise open, the trick is to quickly walk through them. Things inside me are still sprouting upward; still working overtime."

He made his reputation as a photographer for Life magazine, capturing powerful images — both grim and glamorous — from the middle decades of the 20th century, then turned to filmmaking with "The Learning Tree," filmed in his hometown of Fort Scott, Kan., followed by the groundbreaking feature film about a black detective, "Shaft," and its sequel, "Shaft's Big Score." The success of his movies opened the door to other black directors, while he continued pushing open other doors, producing such films as "Leadbelly," composing symphonies and sonatas, and choreographing and scoring "Martin," a ballet in memory of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., which he filmed in 1989.

In recent years, his creative versatility and energy led him to develop an artistic technique that melds photogaphy, painting and poetry. he takes a real object — flower petals, for instance — and makes it the centerpiece of an original painting. He then photographs the abstract composition and pairs it with a poem. His first book in this form, "Arias in Silence," was published in 1994.

A prolific writer, he's authored 19 books, beginning in 1963 with his autobiographical novel, “The Learning Tree," and continuing through "A Choice of Weapons," "Moments Without Proper Names," "Voices in the Mirror" and "Half Past Autumn," a retrospective published in 1997 of his life and work that serves as a sister piece to the traveling exhibition of the same name.

“Half Past Autumn," the exhibition, opens at WSU's Edwin A. Ulrich Museum of Art at 2 p.m., Sunday, May 23, 1999. Parks himself returns to his home state for activities slated around the opening.

"I think of my life in terms of seasons," he says over the phone from his New York City apartment. The sound of his voice echoes the startling dichotomy of his photographic subjects; it is at once softly elegant and as gritty as sandstone. "I think of myself now as being half-past autumn."

Parks' exhibition, which is made possible by major grants from Ford Motor Co. and Time Warner Inc., tells the story of his life through his work and reveals its importance in documenting the social and cultural history of the 20th century. It features 219 photographs, accompanied by films, music, paintings and manuscripts of his poems, novels and other writings.

"His lens has captured history in the making and recorded the many faces of our nation," says Alex Trotman, chairman and CEO of Ford.

Gerald Levin, chairman and CEO of Time Warner adds, "Whether in film, print or photography, Gordon Parks has opened our eyes and challenged our presumptions. He has brought us to a better understanding of our country, our world and ourselves."

A KANSAS SPRING

The youngest of 15 children, Gordon Parks was born in 1912 in the small prairie town of Fort Scott to Sarah and Andrew Jackson Parks, a farmer. Although his mother died when he was only 15, both parents, through their teaching and example, remain his steady guides. They are, he says simply, "my heroes."

"My mother taught me what was right and what was wrong," he says. "She would not tolerate any sort of prejudice against another person. You know, I can feel her looking at me when I do something wrong — even today."

Parks grew up under the pall of poverty and racism. He attended a segregated grade school and went on to Fort Scott's only high school where blacks were banned from playing sports and discouraged from taking college prep courses. He remembers one teacher advising him and his fellow black students against setting their sights on college. They were, after all, destined to become railroad porters and maids, not doctors or lawyers or artists.

Many of his boyhood friends died young, violently. As elsewhere in America, despair erupting in rage had become a product of white society's intolerance — even in a small town in a state born out of principled opposition to the expansion of slavery.

"There was a time when I never wanted to see Kansas again," Parks says. "It was a long time before I could bring myself to it." He adds, "Kansas is a beautiful place. I didn't realize it when I was young." Although his visits are infrequent, he returns to see family and accept honors such as the 1986 Kansan of the Year award.

He never finished high school or attended college. But his early struggles with indigence and bigotry, paired with a natural curiosity about the world and guided by the moral compass provided by his parents, taught him genuine concern for others and the value of real communication.

After his mother's death, he was sent north to St. Paul, Minn., to live with one of his older sisters. Not long after his arrival, he fought with his brother-in-law and was kicked out on a bitterly cold December day in 1928.

INVINCIBLE SUMMER

Homeless and penniless, he sought shelter in a pool hall, slept on streetcars and eventually patched together a living by washing dishes in a restaurant, playing piano in a brothel, touring with a semipro basketball team, even singing with a white orchestra that often played venues which, he notes wryly, didn't allow black patrons. He also fell in love with a beautiful young woman, Sally Alvis, whom he married in 1933. They would have two sons, Gordon Jr. and David, and a daughter, Toni.

Parks was 26 years old and working as a railroad waiter on the North Coast Limited, which ran between St. Paul and Seattle, when he picked up a magazine left on the train and saw the stark, tragic images taken by a group of social documentary photographers for the Farm Security Administration, a government agency set up to aid farmers and create an historical record of conditions during the Depression. Through these images, Parks came to understand the power of photography.

Further inspired by a meeting with Norman Alley, a newsreel photographer, he bought his first camera, a 35mm Voightlander Brilliant, for $7.50 from a Seattle pawn shop. He had found not only a passion and a profession but also, as he later explained, "my weapon against poverty and racism."

Parks launched his photographic career making fashion pictures. But by 1941 he had produced a hard-hitting series about social problems in Chicago. His photography caught the attention of officials with the Julius Rosenwald Fund, and in 1942 he won a Rosenwald fellowship to work in the photographic section of the FSA.

Parks' bold black-and-white FSA photographs of the impoverished black population of Washington, D.C., show his skill in communicating the spirit of a people and the social problems they faced. One of his picutres of a black charwoman, Ella Watson, has become an American icon. Parks photographed Watson standing erectly with a mop in one hand and a broom in the other in front of the American flag. Her gaze is direct; her photographic title: American Gothic.

Parks went on to break the color barrier in fashion photography, working five years at Vogue and Glamour magazines. Then in 1949 he began the 20-year association with Life that brought his work and name into America's living rooms. He traveled the globe for Life, documenting oppressive conditions in the ghettos of Harlem and Rio de Janeiro, introducing America to Red Jackson, a Harlem gang leaders, and Flavio da Silva, a Brazilian street child whose story so moved Life readers that they sent enough money to bring him to the United States for medical treatment.

Parks covered nearly everything: high fashion in Paris; crime in Chicago; Duke Ellington in concert; deposed monarchs living in luxurious exile in Estoril, Portugal; segregation in America's Deep South; the Black Panthers; Ingrid Bergman on the island of Stromboli.

Despite his sincere commitment to family, Parks' drive to excel and his nonstop assignments took a heavy toll on family life. Three times married, he is three times divorced. He and his second wife, Elizabeth Campbell, 27 years his junior, have a daughter, Leslie. He married Genevieve Young, a free-lance editor, in 1973. The major tragedy of his life occurred on April 3, 1979, when his son Gordon, a filmmaker, was killed in a plane crash in Kenya. Parks stays in close contact with his three surviving children, his grandchildren and his three ex-wives.

FRUITS OF AUTUMN

While the camera has been Parks' first choice of weapon in his fight against descrimination, the pen is his second. In the early 1960s he was convinced to try his hand at writing. Like nearly everything he undertakes, he does it well. In 1963 his autobiographical novel, "The Learning Tree," was published; in 1969 the movie version was released. Of all his accomplishments, he consideres "The Learning Tree" his finest.

"Other projects have brought me more money, like 'Shaft,'" he explains. "But 'The Learning Tree' means more. I dedicated it to my mother and father. I wrote it as a way of fighting for civil rights through common sense. Once, when I was discouraged with things in Kansas, I asked my mother if we would have to live here all of our lives. She said I must accept Kansas and our town as a kind of 'learning tree.' That's what she called it, a 'learning tree.' A tree that had good fruit and bad. She said that's the way it was with people. Whether I went or stayed, things would be like that. I would just have to accept it and my experiences as a 'learning tree.'"

Parks did more than accept his experiences, he transcended them, using them as the spur to creative effort. As he puts it: "The awful things laid there in my heart until I had to do something about it." He's quick to add, "The camera is not meant just to show misery. You can show beauty with it. You can show things you like about the universe, things you hate. It's capable of both. I'm concerned with the entire world, and I've come to look for the better things. Every night I offer up a little prayer for the universe."

Architect Charles McAfee has known Parks for more than 20 years now. "Gordon has so much dignity and pride in himself, so much pride and love for his parents and family, so much respect for othes," McAfee relates. "The (attitude) is an example for every young person to learn from, what can be accomplished when you keep your mind straight and stay focused."

One of Parks' poems, "Parting," ends with this line: But be most thankful, son, if in autumn you can still manage a smile.

What brings a smile to the poet's face?

"I'm just happy to be here," Parks says. With a bit of a laugh in his voice, he adds: "You know, autumn is my favorite season."