No. 24 car in a wind tunnel.

Born in the South in the 1940s, the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing (or NASCAR, as you probably know it) has advanced stock car racing from a local hobby to America’s second most popular televised sport — only NFL football is rated higher.

Race car drivers are now adored as professional athletes, endorsing products in TV commercials and appearing on Wheaties boxes like generations of baseball players, boxers and Olympians before them.

The most successful modern NASCAR team is Hendrick Motorsports of North Carolina, with (by the end of 2005) 143 victories and five championships in the highly competitive Nextel Cup racing series. Hendrick is home to superstar drivers Jeff Gordon, Jimmie Johnson, Kyle Busch and Terry Labonte. Hendrick is also home to chief aerodynamicist Kurt Romberg ’86/89, whose behind-the-scenes airflow expertise — forged in the Beech wind tunnel at Wichita State — helps win races.

“When I was in high school I started racing hydroplanes,” Romberg recalls, “and after high school I won a few national championships. My father pointed out that there were no old hydroplane drivers, because at the time, they were dying in competition at a rather alarming rate. I looked around and decided that it was time I get out of racing and find a ‘normal’ life.”

Romberg’s interest in aerodynamics guided his path. He says he believed it “could lead to a ‘normal’ life in engineering, so I looked for a good aeronautical engineering school that was as far away from the hydroplane racing world as possible. I was also looking for a school that had a commercial-level wind tunnel that took on students and could provide valuable hands-on experience. Dad suggested WSU.”

The man Romberg refers to as “Dad” had first-hand knowledge of Wichita State’s aerodynamics program from his own time on campus — not as a student, but as an engineer for the Chrysler Corporation. Gary Romberg came to WSU in early 1970 as part of a team developing the doomed second-generation “wing cars” for Chrysler’s NASCAR program.

“There wasn’t any other wind tunnel we could get into as cheaply,” recalls Gary Romberg, “and it was a good one. We lived in Wichita for a while, six or eight weeks. I remember that the stockyards would burn blood, and that would be smelly, but the steaks were especially good.”

The elder Romberg’s work in the Beech wind tunnel was unfortunately cut short when NASCAR introduced new rules to muzzle Chrysler’s winged supercars, launched the previous racing season and popularized by all-time champion Richard “The King” Petty.

The abandoned “G-series” was never built, and today remains a subject of “what if?” speculation among serious gearheads.

“They didn’t really outlaw (the winged cars),” explains Gary Romberg, “but they said if you’re going to run the supercars, instead of running a 426-cubic-inch engine, you had to run no bigger than a 305-cubic-inch motor, which we called the ‘sewing machine’ engine. A guy did that in ’71 and actually led the race for seven laps!”

Though the project faded into the history books, Gary Romberg remembers WSU fondly.

“My impression of the school was good enough that I sent my son there,” he says. “He bounced around a while, boat racing and all, and I finally said, ‘Hey, you’ve got to decide what you’re going to be. We’re going to send you to Texas A&M or WSU, because they both have good aero programs.’ We took him to Wichita because I figured he couldn’t get into as much trouble there.”

and Kyle Busch (No. 5, youngest driver ever to win a Nextel

Cup race) hammer their cars down a straightaway. These

sophisticated racing machines can reach speeds surpassing

180 mph.

Kurt Romberg is glad that his father felt that way. “There is no doubt in my mind that the experience I gained working at the Beech tunnel, combined with my degree, has provided keys which have unlocked doors,” he says. “The experience and academics also led me to an inherent understanding of the formation of flow fields, which is a tool used daily in this line of work.”

The younger Romberg earned both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree at WSU, then leapt headlong into the world of automotive engineering. He worked for the March Formula 1 racing team in England, but then decided “for a second time” that he didn’t want to make his living in motorsports. “I returned to the States and took a job with General Motors in Detroit working on production car aero,” he says. “I was assigned to the rear-wheel-drive group and started with the 1993 Camaro/Firebird.”

His tenure working on street car design, however, would be limited. “As I began to network through GM,” Romberg explains, “I ran across the GM NASCAR aero folks. Having told myself that I was not interested in racing as a living, I convinced myself that running a few tunnel tests would not be that big of a deal. A year later (in 1997), I handed in my resignation to GM and moved south taking a job with the Pettys as their aero guy. By 1999 I was running the research and development group at Petty Enterprises.”

While at Petty, Romberg oversaw the development of a version of the 2000 Dodge Intrepid, designed and built especially for the NASCAR circuit. But his time there was relatively short.

He migrated to Hendrick in 2001, and has been happily busy ever since, tweaking some of the winningest race cars in history. That being said, Romberg warns that the game of auto racing is a stressful and demanding one. “If you don’t love racing,” he says, “the schedule will kill you. It is extremely hectic.

We tunnel-test one to two days a week, track-test a few times a month, not including the races I attend. We race 38 times between the beginning of February and the end of November, some years going 15 to 20 weeks straight without a day off. The month of January is spent testing and preparing for Daytona, which leaves the month of December to spend time in the shop and at home getting ready for the next year.

“Being a racer,” he continues, “winning is probably the most rewarding part of my job. Enjoying the emotion of victory lane and the congratulatory phone calls from people whom you respect are some of the reasons why I put up with the downsides of racing. Being away from your family is not only hard on yourself but it is difficult on the spouse and children.”

To a lay observer, auto racing may seem like a game of pure horsepower and raw speed, but the aerodynamic design of the cars is also crucial to winning races.

“Nextel Cup is the pinnacle of stock car competition,” says Romberg. “It is this competition that pushes the teams to continuously develop ways to go faster.

Increased aerodynamic downforce and decreased drag are part of making the car go faster. Aerodynamic gains on the order of portions of a percent are significant, as are power gains on the order of single-digit horsepower gains.

“The handling characteristics of a race car are very much a function of the aerodynamic forces on the car. Today’s cars produce between 1,000 and 2,000 pounds of downforce and significant amounts of sideforce. If the balance of this downforce does not match the chassis setup, then the car will be nervous and unstable.

To be successful at this level the drivers and the equipment must compete on the edge of adhesion — and when you are on this edge, the smallest amount of additional downforce or sideforce could be the difference between completing a pass or ending up in the wall.”

This never-ending push for greater speed, handling capability and safety means that new advances in technology are constantly being incorporated into the designs of the cars. Starting next year, a whole new breed of NASCAR machines will be hitting the tracks. Dubbed “The Car of Tomorrow,” this revolutionary design will certainly mean big changes for everyone in the sport, Romberg included.

“This is a totally new car,” he says. “The aerodynamic package includes a splitter on the front of the car, much like what Le Mans and Daytona prototype cars have, and a wing in the back of the car. These two devices will produce more than 50 percent of the total downforce on the car. So the next advance in Nextel Cup aerodynamics will be a thorough understanding of these devices and how to gain a competitive advantage.”

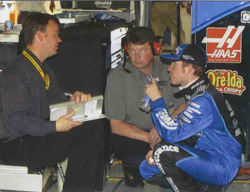

of the car driven by Brian Vickers, right, with crew

chief Lance McGrew. The trio are part of Hendrick

Motorsports of North Carolina, the most successful

modern NASCAR team, with 143 victories and five

Nextel Cup championships.

Even when he’s away from the shop and the track, Romberg maintains a “competitive advantage” over the neighbors: He owns one of the famed wing cars from his father’s heyday, a restored Plymouth Superbird street car.

“I enjoy driving it around town when I get a chance,” he says, though he admits, “it’s getting to the point where I am nervous about getting it out. So many people stare and point that they forget they need to drive. The last two times I had it out I was almost hit by drivers not paying attention.”

Along with about 100 others, Kurt Romberg drove his Superbird around the racetrack at Talladega in 1999 to mark the 30th anniversary of the introduction of the celebrated supercars (which also include the Dodge Daytona).

“There is a certain amount of pride in that car,” he admits. “The fact that Dad had such an important role in something that is now a part of history brings with it a feeling of pride.” The younger Romberg keeps on his desk a photo of himself, his mother and siblings, taken by his father at a Chrysler dealership in 1970 — posed in front of a wing car on the lot.

“It’s really interesting,” says the elder Romberg. “In 1970 and ’71 you could buy a Superbird for $2,995 brand new. A guy I worked with, Dick LaJoy, said, ‘Romberg, why don’t we buy one of those things and put it up on blocks and someday it will be worth something.’ And I told him, ‘Nobody’s ever gonna want one of those.’”

Gary Romberg, now “unretired” and working at North Carolina’s Aerodyne, stayed with Chrysler until 2002. “I was the major mover for the Chrysler wind tunnel,” he explains. “The day it was completed was my last day. After that I knocked around a little bit, did some consulting, kept my hand in a little. Then one day I got contacted by the guy who runs this place. He offered me a job and I jumped at it.”

Aerodyne’s wind tunnel just happens to be used by the staff at nearby Hendrick Motorsports, including Gary’s son. “I see him every Friday here at the wind tunnel,” Gary says.

“He’s happy. I’m happy. That’s the main thing.”