Old legends take a long time to die, and some never do.

Well over a century after the last days of the Old West, the “good guys” and the “bad guys” of that unique period still hold our fascination — none more so than Jesse James.

“I’d been appoached in the past by people interested in similar situations involving Jess James, but I had mixed feelings about digging up a body over intrigue.”

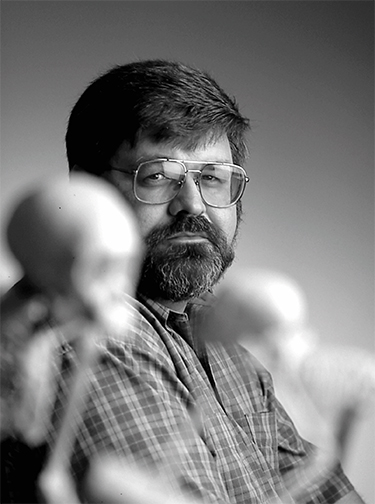

Peer Moore-Jansen

This summer, WSU associate professor of anthropology Peer Moore-Jansen is getting to know a lot about the legendary outlaw.

That’s because Moore-Jansen has been called upon to use his expertise as a forensic anthropologist to lay certain rumors about James — and his death(s) — to rest, once and for all.

Moore-Jansen’s work began in Neodesha, Kan., where the bones of Jeremiah James were exhumed on May 10. This Kansas farmer died in 1935, but rumors about his “real” identity took on a life of their own. Was he Jesse James?

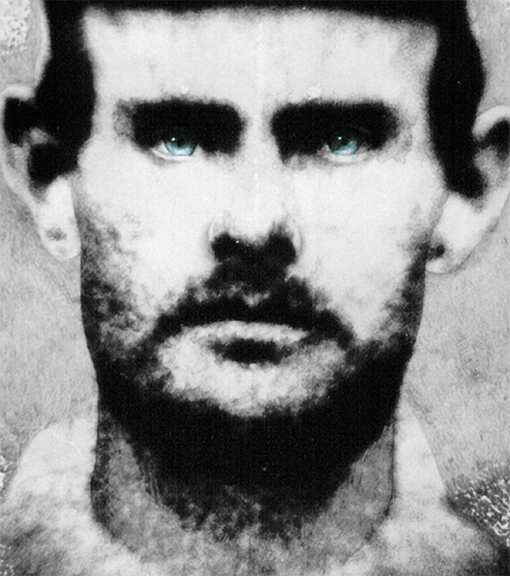

Blue-eyed Jesse Woodson James was born in Kearney, Mo., on Sept. 5, 1847. The son of a Baptist minister, Jesse — joined by his brother, Frank — fought for the South in the Civil War.

Historians say Jesse detested the Industrial North, and some experts go so far as to see in that hatred one of the major reasons he became an outlaw.

“Jesse James (partly) turned to crime as a means of exacting revenge on all things Yankee,” says Time-Life Books’ The Wild West.

Whether that was so, Jesse James certainly learned to kill during the war years while riding with William Quantrill and Bloody Bill Anderson. And in 1866, Jesse, Frank and their cousin Cole Younger embarked on one of the most infamous crime sprees in American history.

By 1873, the James Gang had made the transition from robbing banks to robbing stagecoaches and trains, including the famous Gads Hill, Mo., train robbery of Jan. 31, 1874, in which the holdup men were described as courteous and “rather gentlemanly” and who reportedly only took the money of male passengers who had plug hats and the soft hands of gentlemen.

Those who had the calloused hands of workingmen were left alone. The Gads Hill robbery did wonders for the James legend. To this day, there are those who see Jesse James as America’s Robin Hood.

Through the years, the James Gang pulled off many daring robberies, and Jesse killed a half-dozen or more men. But the gang met its Waterloo in 1876, when attempting to rob the bank at Northfield, Minn. This time, the town people returned fire. All but Jesse and Frank were either killed or wounded and captured.

Spurred on by his wife to lead a more normal life, Jesse and his family moved to St. Joseph, Mo., to hide out in 1881. Living under an assumed name, he rented a house for $14 a month, attended church — but didn’t work for a living. Then in 1882, Jesse tried to buy a farm in Nebraska, but was short of cash.

So he recruited Bob and Charlie Ford to help him rob a bank. On April 3, 1882, while Jesse stood on a chair in his home to straighten a picture, Bob killed him with a single bullet to the back of the head, reportedly for the $10,000 reward.

Since then, rumor after rumor and theory after theory have emerged. Some historians believe the classic story of James’ demise, while others are convinced he faked his own death.

Since there doesn’t seem to be a body of evidence proving one theory over the others, there have been several wild-goose chases in recent years. The fact that the very name “Jesse James” has been popular for decades has only complicated the search.

But with some prodding from Bill Kurtis, a well-known reporter for A&E and the History Channel, and with a little help from Moore-Jansen, the search may be drawing to a close, thanks to DNA analysis.

Moore-Jansen, who expects DNA results on the exhumed body of Jeremiah James to be available in August, initially had reservations: “I’d been approached in the past by people interested in similar situations involving Jesse James, but I had mixed feelings about digging up a body over intrigue.

It took some time. Eventually, I was contacted by Kurtis Productions and then retained by them.” He stresses that he did not become involved out of sheer curiosity. “I’m not being paid for this, nor am I doing it for profit. I think there is some professional information to be gained from this exhumation, and that’s why I became involved.”

People tend to regard DNA these days as the end-all, be-all, but Moore-Jansen says DNA can be difficult to read correctly. “Since 1991, there have been two or three other exhumations, and many feel strongly about the (resulting) evidence.

However, the question is: ‘How much is certainty?’ DNA can look identical when you’re comparing family lines, so if these bodies were somehow related to Jesse James, then the the DNA might look the same but still not be James. In addition to DNA, skeletal evidence must be taken into account. Do the wounds on the skeleton match those he was supposed to have had?”

Among Jeremiah’s descendants, sentiments about his identity are split. His great-granddaughter, Nancy Haviland, told ABC news she was skeptical, in part based on family recollections and descriptions of Jeremiah whose eye color — brown — contradicts Jesse’s blue eyes.

Another descendant, Chuck James, told ABC that as an American history buff, he was excited about the prospect that yet another chapter might unfold in the legend of Jesse James. Regardless of the outcome of the DNA testing, the body will be returned to its original resting place and the gravesite will be restored to its prior condition, something that eventually won over those family members opposed to the exhumation.

And, too — so many of the outlaws of the Old West were either finally captured or killed, whereas Jesse James managed to elude the law his entire life, whether his life ended in 1882 or 1935. Wherever the real James is, he has to be smiling: After all this time, he still has us on the run.