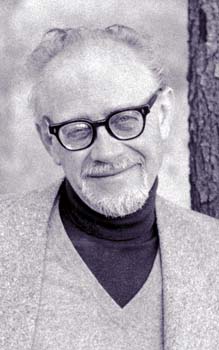

1995, had a special knack for

teaching — and entertaining.

One of his former students

takes a Look Back at this

formidable English professor.

I remember going to my first class in “Introduction to Graduate Studies” with some trepidation.

It was being taught that semester by the formal and formidable Professor James Merriman, whom I had never taken an undergraduate English class from, but comments by classmates had led me to fear him just a little.

He was a legend in the department not only for a profound passion for his specialty — Tennyson — and for language and literature in general, but even more so for his ardor for rigorous scholarship. I was fervently hoping that he would not at last perceive me to be a fool.

Professor Merriman announced that we would be studying Ibsen’s The Wild Duck, and only that, for the entire semester.

He was interested, he said, in discovering the smallest element — be it a word, a phrase, a sequence — by which a work of literature could be deconstructed such that the structural significance of the work, and by inference, all works of literature, would be made manifest.

Some in the class were perplexed. Others, who had been hoping to learn the “meaning” of certainly more than one work, were aghast. Still others, including myself, were intrigued; he was, after all, talking about a Holy Grail of the Kingdom of Literature.

Professor Merriman said that we would work with the play because a play features dialogue and that dialogue seemed a promising place to start —why, I don’t remember. He proposed that we try to ferret out what he had decided to call the “Edited Dialogue Unit,” or EDU, for investigation. We quickly got nowhere with simple classroom trial and error, so he suggested it might be best if we went to the library to consult, and of course evaluate, the usefulness and the credibility of promising secondary source material.

Daily, we visited Ablah Library to pore through the card catalogue and then through books, journal articles, abstracts, and the like. We filled note cards and notebooks with bits of knowledge, insights, conjectures and concepts to apply to the play.

In the classroom, we reported, singly and in groups and in short papers, what we had discovered. And what we discovered most of all was that we were no closer to finding that blasted EDU.

In the fifth week, I got it. I had entered the course expecting to grapple with profound lectures on theories and applications of scholarship, but I realized that the Machiavellian Professor Merriman had instead literally cut to the chase.

In pursuing the elusive EDU, we were not merely reading, hearing and talking about meticulous research — we were performing it. His ploy left me breathless. I suspected that he didn’t care whether we found an EDU or not, but I pressed on in the quest.

Near the end of the penultimate class, he declared, “And so it appears that there is no such thing as the Edited Dialogue Unit. But be not dismayed, because among all the theories you will propose and encounter hereafter, the EDU is one that need never engage you again.

So our research has after all borne fruit, small though it may be.” Those few who were still clueless about his clever ruse groaned and sighed. During the final class, he read poems by Tennyson — beautifully, eloquently — and then he smiled cherubically and said, “Ladies and gentlemen, thank you for the pleasure of your company.”

Time passed. My husband — one of Professor Merriman’s junior colleagues — and I became friends with Jim Merriman and his just-as-wonderful wife Mira. We would have dinner at their home or they at ours, we enjoyed marvelous conversations and abundant laughter, and at the end of each such occasion, Jim would gently grasp our hands and say, “My dears, thank you for the pleasure of your company.”

And then, in Italy, his heart began to fail, and he and Mira flew back to the states seeking expert medical help, but it was ultimately another wild-goose chase, this time of mortal significance.

He died and was buried in Connecticut. Under a canopy of venerable old trees, adjacent to his gravestone and hers, Mira had a granite bench installed for the comfort and repose of visitors, which bears the words “Thank You for the Pleasure of Your Company.”

I think of Professor Merriman often. With the EDU as bait, he had engaged us in a glorious snipe hunt on which we discovered for ourselves the rigorous practice and unabashed joys of scholarship, which discipline I have profitably enjoyed nearly every day since.

He was the most extraordinary teacher I have ever had the delight to work with, so I’m especially grateful now for the opportunity to say, “Dear Jim, thank you for the pleasure of your company.”