The beat of their wings disrupts the quiet of evening as the crows — a beautiful, black murder of crows — return from a day in the fields to the city’s trees to roost. Like a black-water vortex, they fluidly circle the sky before alighting on high branches and settling in for the night. They caw and cackle. Some squabble. Some preen. But as the moon rises and night falls, their feathery rustlings merge with the wind in a soothing yet unsettling song.

America’s Beat movement is strangely soothing and deeply unsettling, exactly as any electric revolution in art, manners and consciousness should be. Its sources span the globe and the centuries, from the 6th century bce teachings of Siddhartha Gautama, through England’s 18th century visionary poet William Blake, to the existentialism of France’s Jean-Paul Sartre and the poetry of American-born Ezra Pound in the 20th. American music — most especially jazz — lent a sense of spontaneity’s structure. Yet no source was as singularly fertile to the Beats as the interior wilderness of the individual mind.

Its successes are as far-ranging. Like elementary particles, the products of its poets, novelists, filmmakers, painters, playwrights, assemblage artists, photographers have become “smeared out” in our wider culture, enfolded in our world view. The energy, velocity and spin of their creations can be seen in the quick-cuts and image intensity of an mtv video, felt in the ever-widening circle of environmental awareness and concern, heard in the revival of the ancient oral tradition of poetry through readings and collaborations with musicians, and touched, perhaps most deeply, in a strengthened impulse toward an individual’s freedom to wing one’s own way through life.

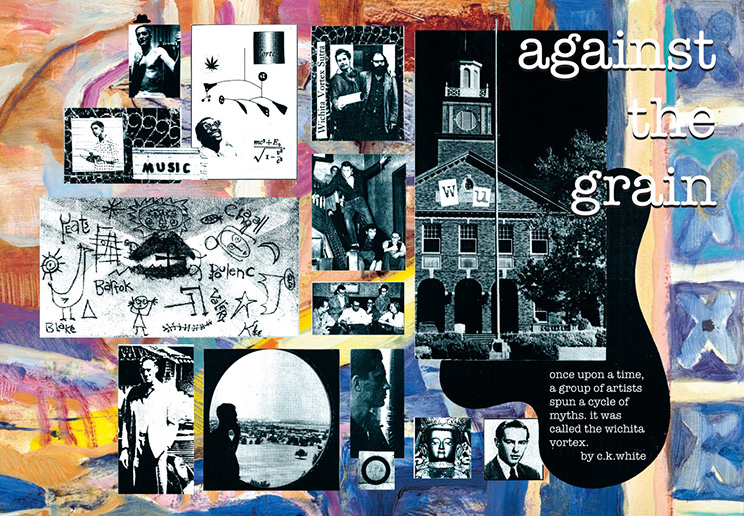

Quite impressively, Wichita and its schools sent to flight literally scores of Beat artists: Michael McClure, Bruce Conner, David Haselwood, in a first migration; Robert Branaman, Charles Plymell and others, in a second. Many of them — so independently minded, so unique, their works — transcend limiting labels. Yet their collective story mirrors a wider stirring, called, for the moment at least, Beat.

As movements go, this one is young, having taken its first gasps of breath in 1944 with the coming together in New York City of William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac. Critic Ann Douglas has come to regard Kerouac as the movement’s “mythologizer,” Ginsberg as its “prophet” and Burroughs, its “theorist.” Read as a kind of Beat triptych, their best-known works — Ginsberg’s poem Howl (1955), Kerouac’s novel On the Road (1957) and Burrough’s avant-garde narrative Naked Lunch (1959) — are acts of sabotage aimed not only at blasting the accepted definitions of what constitutes literary art, but also, on a wider plane, undermining the rigidly programmed dictates of “duty” and “respectability” in post-World War II America.

A new impulse, in friction with the old, had sparked into existence.

MARTIAN HISTORY STUDIES

As Burroughs, Ginsberg and Kerouac ingested the raw materials for their creative work in nyc and elsewhere, similar swirls of people coalesced in cities and towns across the U.S. “Who knows how to explain it,” says Jim Johnson ’75, an art historian and independent curator. “You might as well say something was in the water or the air. Whatever it was, you began to see groups of people in the late 1940s and early ’50s producing similar kinds of art and holding similar attitudes about art.”

In Wichita, such groups first formed in the city’s junior high schools. “I’m afraid,” wrote McClure fs ’53 in Lighting the Corners: On Art, Nature, and the Visionary, “that many people today that were not alive in the 1950s have a vague idea of what the ’50s were like. This was the period of the Cold War — you can imagine Bob Dylan as a 12-year-old boy watching the McCarthy hearings on television.”

Or to shift the scene a few years earlier, you can imagine McClure himself as an eighth-grader in Wichita at the close of WWII, ‘ducking and covering’ right in the center of a country intent on consolidating its military/industrial might. “Driven by defense spending during the war years, Wichita’s economy increased and its population doubled, from 100,000 to roughly 200,000,” says Craig Miner, wsu distinguished professor of history. “It was a time of hysteric growth.”

David Quick, a photographer, filmmaker and wsu lecturer, stresses, “The fact that one of Wichita’s primary industries, aviation, was related to death wasn’t lost on at least some of the city’s youth. They knew they were living, symbolically, in a pit of death.”

Against that backdrop, McClure met another eighth-grader, Lee Streiff, at Robinson Junior High. It was Streiff who passed on the science-fiction tale of The Epic of the Martian Empire, written circa 1937 by his older brother, James. No one knew it yet, but within the epic’s cycle of stories was the germ of the Wichita Vortex, a concept that would shift shape and meaning and grow into, as Johnson puts it, “the story that became both a description of dire circumstances and the name of a place.”

To use a term from Streiff’s The Vortex Souvenir Book, printed this year by his own The Vortex Press, the “proto-beat” groups in Wichita were strengthened during high-school years, notably at East High where McClure and Streiff met Haselwood and Conner. And they merged at Wichita University in the early ’50s.

Provincial Review

Recalling his WU days, Streiff says, “Our lives became one long party and one long discussion.” He adds that group members “were circulating our writing informally in a variety of ways: handwritten, typed and carbon copies were passed along from one person to another, and people sometimes read or recited their works in conversations over coffee at Manning’s or over beer at The Blue Lantern or at parties.”

It was at gatherings such as those that stories from the Martian Epic were transmuted into the idea of the Wichita Vortex. “The Vortex myth was based on the concept that we — Eric Ecklor, Loren Frickel, Lee Streiff, Bruce Conner, Jack Morrison, Michael McClure in specific and the residents of Wichita in general — were held captive as outlaws of another planet,” Conner explained in a 1987 letter to Robert Melton of the University of Kansas. “We were deposited annually in Wichita and endowed with fabricated memories at the time of the wu Homecoming game. We could never leave Wichita. All outside of Wichita was an illusion of the Vortex.”

But many of them would leave Wichita, adding another layer of meaning to the Vortex myth. Streiff explains, “For many, a defining peculiarity of Wichita’s culture was a slow-motion exodus that ebbed and flowed, carrying the youth of Wichita out across the continent. Sometimes they stayed where the flood had carried them, sometimes they returned — only to push on again.”

Members of this dynamic group of young writers and artists thought, played and stayed at wu long enough to initiate a number of cultural artefacts: a weekly, folk-music radio program on kmuw; an occasional Literary Review inserted in the student paper, the Sunflower; the wu Film Society; and, founded by Corban LePell in 1958, the university’s still extant literary publication Mikrokosmos.

One of their earliest undertakings was coming up with a Machiavellian plan to fund the publishing of a literary magazine. Based on the premise that the established wu writers’ group, the Quill Club, had funds for such a venture, McClure, Streiff and others determined during the 1951-52 school year to join the club and take over control of its resources. Armed with a copy of the club’s constitution, they manuevered to get Streiff elected president and Haselwood, vice president.

The victory was less sweet when the new officers and members of the newly renamed Writers Club discovered their organization was $350 in debt. Still, they pulled together to resolve the debt and set to work on their magazine, Provincial Review. Conner drew the cover. An editorial policy and manifesto was adopted, based heavily on ideas in Ezra Pound’s Vortex Manifesto. Manuscripts were collected and reviewed by the editorial board — Haselwood, McClure, Conner, Ecklor and Streiff. They even toured local printers’ offices, Streiff recalls, “as McClure suggested, dressed like farm laborers to avoid paying high rates.” But for a number of reasons, chief among them personal disputes among key players, the project fell apart, and the magazine was not published — then.

In 1996, Streiff and Conner put the Provincial Review into print, with original artwork, stories and even ads. It is a document of the times — and of some of the early works of three art-world luminaries.

THE WICHITA GROUP

Strictly speaking, the Wichita Group is a trio: McClure, Conner and Haselwood. After leaving Kansas, each, independently, “found home in San Francisco,” Johnson relates. There, they made art history.

McClure, in 1955, was one of six poets who read their works at the Six Gallery in San Francisco, the reading at which Ginsberg first read Howl. A prolific poet and playwright of astonishing power and inventiveness, he is perhaps most widely known for his complex nature poetry and his play, The Beard, about an imaginative meeting between Billy the Kid and Jean Harlowe. The play is on tour with the Riverside Repetory Theatre Co.

Conner, whose art resides in the permanent collections of the world’s great art museums, is a multifarious artist renowned for his experimental films, drawings, paintings, collages, photographs and assemblages. His wide-ranging sensibility can be seen in the museum survey comically titled 2000 bc: The Bruce Conner Story Part II, now at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art.

Haselwood garnered his acclaim through printing. His Auerhahn Press published the works of many of the Beat writers — in beautiful, hand-made books.

WICHITA VORTEX SUTRA

Back in Wichita, a second wave of Beat artists was cresting: Bob Branaman, Jim Davis, Bruce McGrew, Jim Mechem, Joan Pepitone, Charles Plymell, Alan Russo, Glenn Todd…

After Branaman, a visual artist and filmmaker, Plymell, poet and author of The Last of the Moccasins, and others arrived in San Francisco, the Beats there became even more fascinated with the Vortex, with Wichita. It was intriguing to them that, although conservative, the city was producing so many, Streiff says, “brilliant artists and sensitive poets.”

Many Beats traveled to Wichita to see for themselves. Ginsberg’s 1966 visit was the most famous. Sponsored by wsu’s Philosophy Club, Ginsberg performed on campus at the student center. Although viciously critical of what Wichita symbolized to him in his Wichita Vortex Sutra, the poem is the final proof of the power and the pull of the Vortex.

And despite the light-years of difference between each of the Wichita Vortex artists, this much, they had, and have, in common: they cut their art new and against the grain.

In the process, they pried our eyes and minds — even, perhaps, our hearts — just a little wider open.