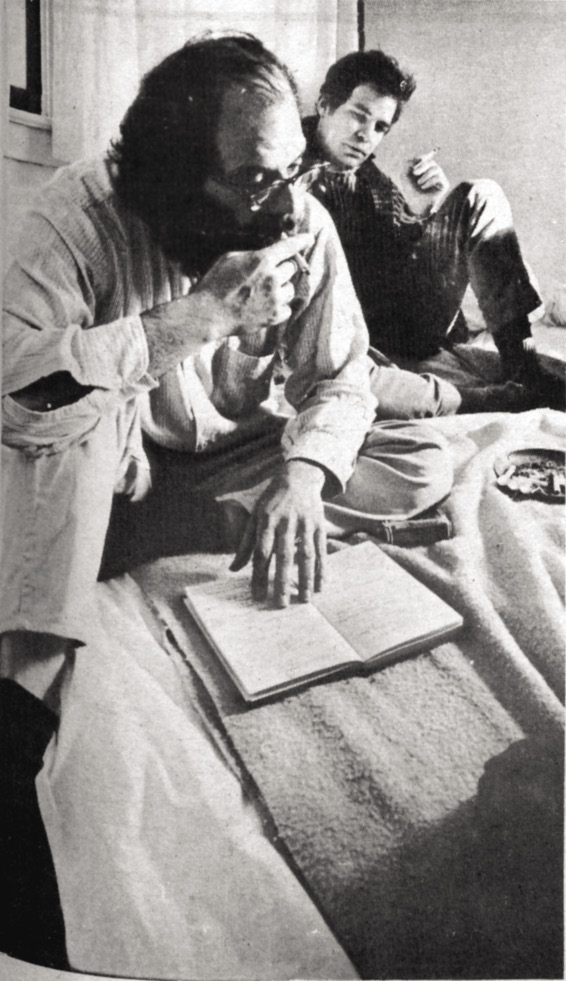

February stay in Wichita. The poet’s trip to Wichita was a productive one,

resulting as it did in Wichita Vortex Sutra, an antiwar poem that became

one of his best-known works. Photos: Wichita State University Libraries,

Special Collections and University Archives.

It was a different time.

The feel of the Sixties was of a different texture. Different somehow than the cottony Fifties. Rough like hemp. The look of the Sixties was appropriately bizarre, as suits a time of testing boundaries. The music (The order is rapidly fadin’. / And the first one now will later be last. / For the times they are a-changin’.; Purple haze gets in my eyes. / ’Scuse me while I kiss the sky.) and the sounds (Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.; I have a dream …) are those of explorers.

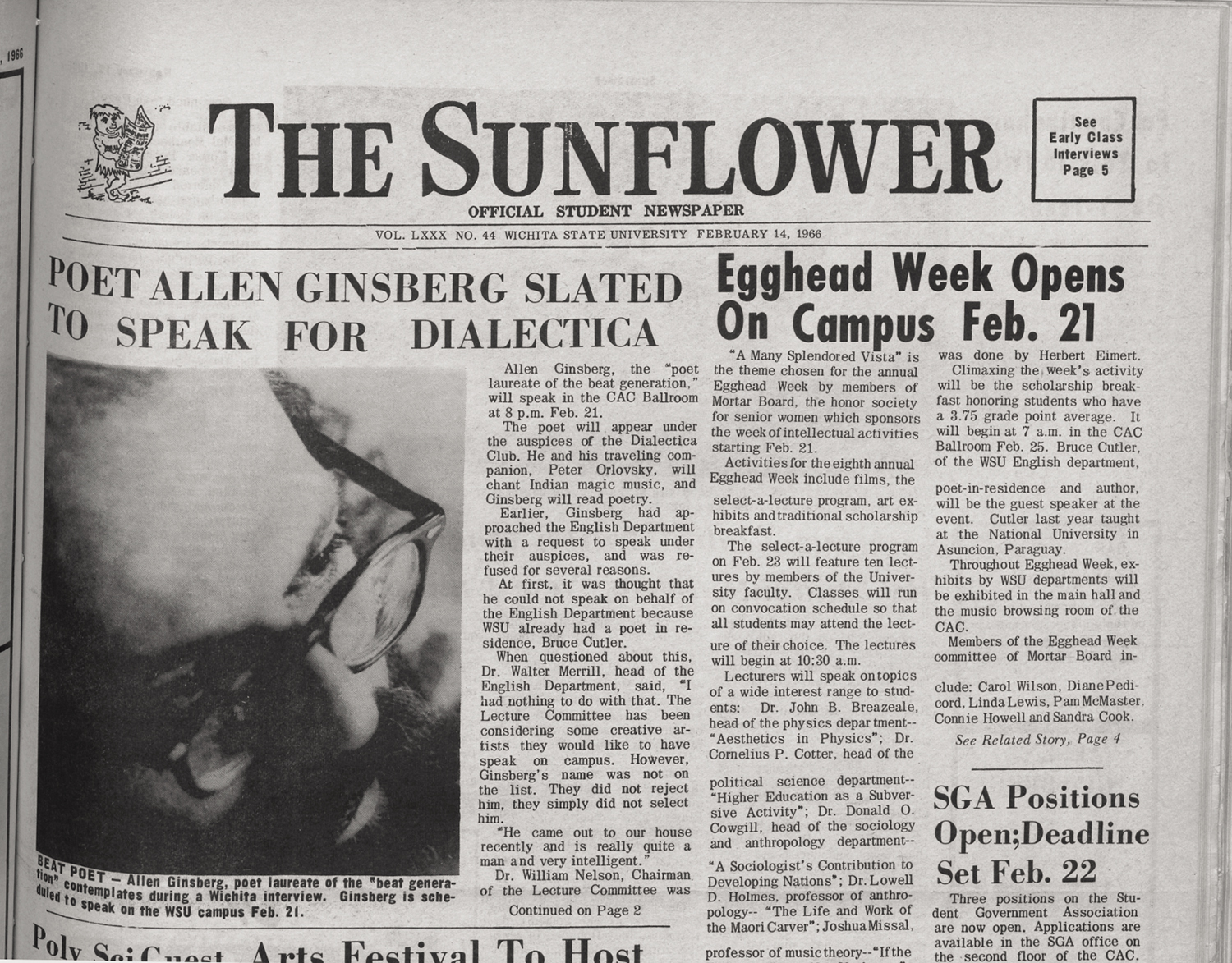

One of those explorers, the poet and counterculture icon Allen Ginsberg, beat a newsworthy path to Wichita at least twice in the 1960s — and once, on Monday, Feb. 21, 1966, his destination was Wichita State, the Campus Activities Center Ballroom, to be specific.

Appearing under the auspices of Dialectica, the university’s philosophy club, Ginsberg “warmed up the audience of some 300 with Indian magic chants. Then, after several lighter poems, he began his poetic harrangue (sic) with all the mysteriousness of a Buddhist monk,” as Dan Garrity reported the proceedings in “A Poet’s Pilgrimage,” which the student newspaper, the Sunflower, published in its Feb. 23 edition.

It is interesting to note, as reflections of the times both on campus and in the wider world, the titles of two of that edition’s front page articles: “Egghead Week’s Theme Many Splendored Vista” and an AP story “Bell Bottom Pants Predicted for Men.”

Ginsberg’s poetic harangue was Wichita Vortex Sutra, written (specifically, spoken into a tape machine) just the weekend before during a quick side-trip north to the University of Nebraska, Lincoln. Considered by a number of critics as one of the most heartfelt and artistically relevant responses to the horror of the Vietnam War, Wichita Vortex Sutra speaks of the power of language to communicate the truth but also to manipulate the hearer, for better or worse.

In the poem, Ginsberg juxtaposes images of the Kansas landscape with snatches of media reports on the war in Vietnam. Viciously critical of what Wichita symbolized to him, he castigates the city for being a wasteland, especially for its younger citizens: “The city imposes a dark night on the soul of its youth,” as Ginsberg told the Wichita Eagle during an interview in early February.

Ginsberg had traveled to Wichita three years earlier to see Charles Plymell fs ’61, one of a half dozen or more Wichita

poets and artists whom Ginsberg met in California. Among

them was Michael McClure fs ’53, who in 1955 was one of six poets who read their works at the Six Gallery in San Francisco, the reading at which Ginsberg first read Howl, his most famous poem with its long, free-flowing, stream-of-consciousness

leading line that begins: “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked …”

Other former Wichitans whom Ginsberg knew and whose works he praised included two visual artists and filmmakers who, like McClure, had studied at the University of Wichita before setting out for the West Coast to make their livings and their art: Bruce Conner fs ’53 and Bob Branaman fs ’59.

When Ginsberg came to Wichita in 1966, arriving on Feb. 4 well before his reading at the CAC, he was traveling cross-country (funded by a Guggenheim grant) on a search for America. As Walt Whitman, Thomas Wolfe and his close friend Jack Kerouac had done, he hit the road on an expedition to better understand America and its people.

Ginsberg, along with two traveling companions, left San Francisco around Dec. 18, 1965. He stopped in Wichita, staying at the Eaton Hotel, because it was intriguing to him that, although conservative, this city on the plains was producing so many innovative artists. While based in Wichita, Ginsberg took side-trips to Topeka and Lawrence, in addition to Lincoln, Neb. He and his party then journeyed on to Kansas City and eventually ended their trek in New York.

Predictably, Ginsberg’s appearance at the CAC elicited mixed responses. As the 1966 Parnassus capsulizes his visit: “Undoubtedly, the most controversial figure to appear on campus this year was Allen Ginsberg, beat poet and bearded philosopher. … The decision on Ginsberg was up to the individual student — was the poet Base or Basic? Was it a matter of Intellectual Activity or Exhibitionism? Whatever the individual’s decision, at least students were given an opportunity to reflect upon what they considered the Bounds of Propriety, both privately and publicly.”

Even before Ginsberg spoke on campus, charges of suppression of free speech were being made. Roger Irwin, graduate fellow and instructor in WSU’s philosophy department (and Ginsberg’s friend), claimed that an official university warning to Ginsberg to keep his reading within the bounds of propriety was an “attempt by the administration to limit freedom of speech,” as reported in the Sunflower article “Instructor Claims Free Speech Violated in Warning to Poet.”

The warning was given during a conference with Kelley Sowards, WSU dean of liberal arts, Bobby Stout, head of the Wichita police vice squad and Ginsberg and his lawyers. Sowards is quoted in the Sunflower as explaining, “The last thing we wanted was to have a nationally known figure arrested on campus. We wanted to handle it ourselves. The whole thing worked out nicely — a huge success — with a controversial figure appearing on campus without incident.”

Indeed, the attendees of Ginsberg’s performance (WSU students, townspeople, a Life magazine reporter, people from Greenwich Village who were making a movie, and members of Wichita’s vice squad) seemed to get along just fine.

A month-long exchange of letters to the Sunflower followed the poet’s reading. Some were full-blown pans, a few were full-on supportive, and a good number were written tongue-in-cheek, including one by WSU sophomore Betty James, who wrote, in part: “The college and the police are to be commended for their immediate and capable surveillance of the Ginsberg problem.”