Wichita State anthropology professor and archaeologist Don Blakeslee was reading a new translation of an old account of a 1601 hostile encounter between Spanish explorers and Native Americans near the site of a “great settlement.” No one knew for sure just where this was, although there were clues. As Blakeslee read, a quite definite location kept coming to mind. “I wonder,” he thought. “I wonder …”

As it has played out, Blakeslee’s flash of recognition was right on point — and it pointed to a rock-lined gully, thick with walnut trees, near the Walnut River’s edge just east of Arkansas City, Kan.

Evidence uncovered during a five-day archaeological field study that Blakeslee led in early June of last year to check his hunch has indeed established this as the site of that long ago clash between Spanish conquistadors and Native Americans.

It was 415 years ago when Juan de Oñate, the colonial governor of the Santa Fe de Nuevo México province in the Viceroyalty of New Spain, set out from New Mexico with his soldiers for the southern Plains, marching through parts of modern-day Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas.

Oñate and his party — said to have comprised a dozen Franciscan priests, some 130 Spanish soldiers with several cannons, as well as a retinue of 130 Native American scouts, soldiers and servants — had their sights set on finding treasure, gold in particular.

That didn’t happen. But they saw herds of American bison, and the Spanish among them marveled at these “most monstrous cattle.”

They witnessed the vast expanse of the Great Plains and noted the richness of its soil-entangling grasses, in places so high that “they hid a horse.”

And they saw, straddling the banks of a river not far from its confluence with a larger river, more than 1,000 large, round, grass-thatched houses clustered in small groupings among little fields of maize, beans and squash, a trio called by Native Americans the “three sisters.”

The general whereabouts of a “great settlement” called Etzanoa had been pointed out to Oñate by members of a native people known as Escanxaque. The Escanxaque, from parts of present-day Oklahoma, were bison hunters who planted no crops. And they were enemies of the Rayado — from Etzanoa.

Before Oñate’s expeditionary force, accompanied by a contingent of Escanxaque, caught sight of Etzanoa, they had encountered a group of Rayados and detained their chief as a guide and hostage, although, accounts claim, “treating him well.”

Upon arrival, they found the settlement all but deserted, the inhabitants having fled their approach.

With so many conniving intrigues and hostile schemes in play, tensions were building on this stretch of the plains in early summer of 1601.

Oñate determined to turn his men around and return to Nuevo México. But before they could get out of the territory, the Escanxaque turned on them and a pitched battle ensued.

The Spanish were outnumbered, but the superior firepower of their guns and cannon eventually forced their foes to seek shelter in a rock-lined gully.

Oñate and his men made it back to their base in New Mexico that fall and reported their findings to Spanish officials – including the estimate that some 20,000 people resided at Etzanoa, in its scatter of houses whose end “was not

in sight.”

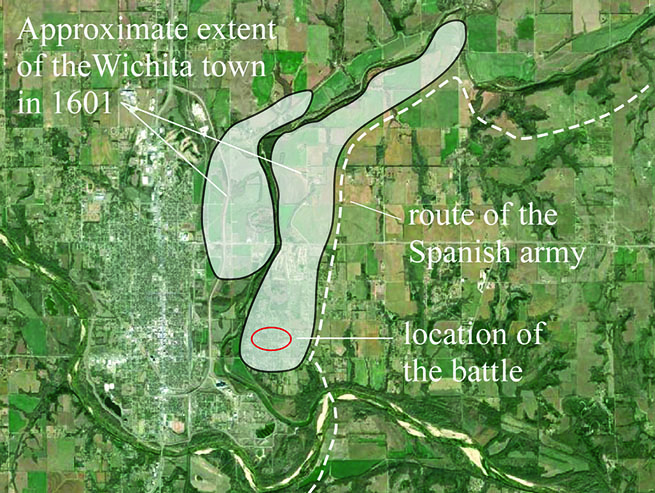

surroundings is a graphic of the probable extent of the protohistoric

Wichita settlement of Etzanoa, perhaps the largest Native American

settlement in the United States — surpassing Cohokia in what is today

Illinois. Also shown are the route taken by Spanish conquistadors led

by Juan de Oñate and the site of the “Battle of Etzanoa.”

That estimate would make Etzanoa among the most populous Native American settlements in the United States, perhaps second only to Cohokia, near today’s St. Louis, which at its peak in the 13th century is thought to have had a population of some 40,000. In its heyday, the city limits of Cohokia probably encompassed just over six square miles.

Etzanoa was thought to cover some five square miles. But that, says Blakeslee, may not be at all accurate. He’s sitting in front of a computer in a second-floor Neff Hall work room going through digital photos of artifacts found at various Etzanoa locations, including five main sites along the bluffs overlooking the Walnut River.

The sites include plowed and unplowed fields, residential properties and the fairway of a golf course. Among the finds are two iron balls and a lead bullet recovered near rocks in the gully Blakeslee had identified.

Because they match the types of ammunition used by the Spanish in their cannon and guns of the early 17th century, they are evidence that the site really is that of the “Battle of Etzanoa.”

Blakeslee’s years of archaeological digs have made him a respected expert on the Plains Indians, including the Caddoan Wichita, among whose ancestors were likely to have been the Rayado.

These protohistoric Wichita left signs of how they lived at Etzanoa, and last June Blakeslee, five other archaeologists, half a dozen Wichita State anthropology students and a corps of local volunteers set out to find them.

“We had a lot of volunteers,” Blakeslee reports. “We found a huge distribution of chipped stone” — which is the tell-tale marker of stone toolmaking activity. Blakeslee and his team also found in abundance stone tools used in the hunting and processing of bison, as well as tools associated with farming or horticulture, including a bison shoulder blade used as a hoe.

Faced with so much evidence of a large, thriving settlement, Blakeslee and others became ever more convinced that the lower Walnut River valley was indeed the site of Etzanoa.

But archaeologists are a cautious breed, and Blakeslee called for yet more investigation. “We ended up bringing in a magnetometer from the National Park Service,” he explains.

Focusing on a location north of the battle site, the magnetometer produced an image that reveals circular areas dotted with black spots. “The circles here,” Blakeslee says, pointing to his computer screen, “are clusters of houses. The black dots here are storage pits. What we found matches just what the Spanish described.”

The descriptions recorded by one Spaniard in particular, Baltazar Martinez, were helpful to Blakeslee. Martinez kept detailed notes about the houses at Etzanoa and even took measurements of the distances between the clusters. “From him,” Blakeslee says, “you get a very, very clear image of how everything was laid out.”

Before smallpox decimated Native American populations, they built complex settlements that sometimes grew to metropolitan status. One of them, the Mississippian culture’s Cohokia, rivaled Europe’s largest cities of the time.

They developed complicated societies with intricate religious rituals and beliefs. Although they didn’t use currency, they formed extensive trade relationships.

The protohistoric Wichita, for example, traded with native peoples of the Southwest, as evidenced by the presence of obsidian, turquoise and Southwestern pottery at some of their settlement sites.

Based on a Spanish account that tells of native people at Etzanoa (and places farther south) talking in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztec and the lingua franca of Mesoamerica, Blakeslee thinks it’s possible that Etzanoa’s trade reach was significantly more far-ranging than to the relatively close Southwest.

He also thinks, and so far is backed up with evidence, that Etzanoa will turn out to be the largest Native American settlement site in North America. See those two gray-shaded areas on the map pictured above that shows the probable extent of Etzanoa? It’s an area of 15 miles.

Blakeslee: “How cool is that!”

TOOLS OF THEIR TRADES

Artifacts found at the site of Etzanoa, which once flourished along the Walnut River Valley on the east side of today’s Arkansas City, Kan., speak to the lives and livelihoods of the ancestors of the Native Americans called Wichita.

Protohistoric Wichita settlements, including Etzanoa, are known in archaeological terms as the Great Bend aspect. Chronologically, Great Bend sites are thought to date from AD 1400 to 1700, by which time the Wichita had begun a migration to the south.

The material culture of the Great Bend aspect at the Etzanoa site seems to mirror the lifestyle of a horticultural people with a strong reliance on the hunting of bison.

Many of the artifacts uncovered to date by Don Blakeslee and others are indeed tools of the bison-hunting and processing trades.

From the top at right are Fresno projectile points (lines 1-4), awls, or drills, (lines 5-7), scrapers (lines 8-10) and knives (lines 11-12).

Fresno points, which are typical of what archaeologists term the Middle and Late Ceramic Periods, date generally from between AD 1250 and 1700, are triangular in shape and lack notches of any kind.

Stone awls were used to drill holes in, among other things, the thick buffalo hides that were processed after the hunt.

Flint scrapers were used chiefly for the preparation of hides for clothing and bedding.

Commonly divided into two broad types, end and side scrapers, depending on which part of the flake was used to form the scraping edge, the artifacts shown here are all end scrapers.

Along with projectile points and scrapers, knives are often one of the most common artifacts found at a site, as was the case at Etzanoa.

The knife was an essential tool for various types of cutting purposes, including the cutting of bison hides and meat.

Taken together with other artifacts collected within the known extent of the Etzanoa site, including mauls and pipes, as well as the identification of a carved-rock ritual site (pictured at top), these tools hint at a long and captivating — and still mostly lost — tale of hunting and warfare, agriculture and trade, religion and art.