You might say Wichita State's Donald Blakeslee lives in the past. After all, he has spent countless hours plumbing its ground layers and searching its dark, rocky overhangs looking for clues to such trailings from days gone by as the illusive path of Spanish explorer Francisco Vazquez de Coronado and the tell-tale markings that allow glimpses into the lives of the natives of the Plains. Now, he's lifting his inquisitive eyes to the ancient skies.

From Texas to Alberta, the natives of the Plains made pilgrimages to sacred sites. These included natural features such as Colorado's Manitou Springs, Nebraska's Guide Rock and meteorite fields in Kansas.

—Don Blakeslee

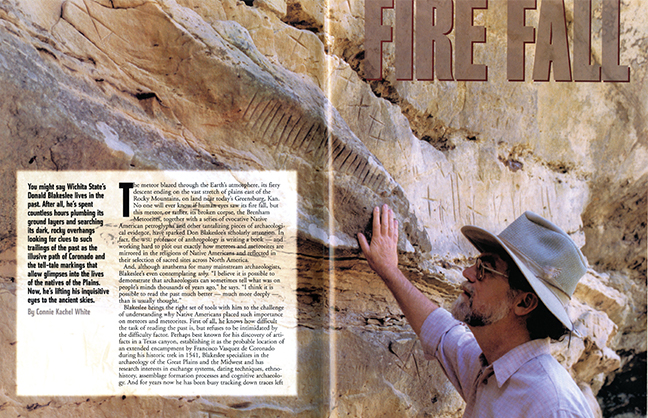

The meteor blazed hrough the Earth's atmosphere, its fiery descent ending on the vast stretch of plains east of the Rocky Mountains, on land near today's Greensburg, Kan. No one will ever know if human eyes saw its fire fall, but this meteor, or rather, its broken corpse, the Brenham Meteorites, together with a series of evocative Native American petroglyphs and other tantalizing pieces of archaeological evidence, have sparked Don Blakeslee's scholarly attention. In fact, the WSU professor of anthropology is writing a book — and working hard to plot out exactly how meteors and meteorites are mirrored in the religions of Native Americans and reflected in their selection of sacred sites across North American.

And, although anathema for many mainstream archaeologists, Blakeslee's even contemplating why. "I believe it is possible to demonstrate that archaeologists can sometimes tell what was on people's minds thousands of years ago," he says. "I think it is possible to read the past much better — much more deeply — than is usually thought."

Blakeslee brings the right set of tools with him to the challenge of understanding who Native Americans placed such importance on meteors and meteorites. First of all, he knows how difficult the task of reading the past is, but refuses to be intimidated by the difficulty factor. Perhaps best known for his discovery of artifacts in a Texas canyon, establishing it as the probable location of an extended encampment by Francisco Vasquez de Coronado during his historic trek in 1541, Blakeslee specializes in the archaeology of the Great Plains and the Midwest and has research interests in exchange systems, dating techniques, thno-history, assemblage formation processes and cognitive archaeology. And for years now he has been busy tracking down traces left by the Great Plains dwellers and others that show they attached special meaning to meteors and meteorites, which hold within them so many opposite attributes: Showering from the sky in fire, they fall to the earth and turn cold to the touch. They can "weep" as chemical reactions take place inside them; and polished, they can become dark mirrors. And, as Blakeslee, his former student and now colleague Robert Blasing '86 and other researchers have discovered, "mirrors" played a key role in many Native American traditions.

Yellow Star

Meandering through every known early civilization and heading back well into the haze of prehistory, man's cultural trail is littered with artifacts showing the religious significance of the sun, the moon and many other heavely bodies. On the Great Plains, where the sky is paramount, it is little wonder the sun, moon, planets, stars, comets and meteors became so familiar to the Native Americans who lived there and who built all kinds of astronomical observatories, from the highly complex such as the Bighorn Medicine Wheel in Wyoming to the beautifully simple.

For example, one earth lodge in Iowa has an opening that frames a view of a lone hill, behind which the yellow star Capella makes its first seasonal appearance. Capella is one of the brightest stars in the sky, and scholars believe that Native Americans may have used the heliacal risings of bright stars to coordinate their fluctuating lunar calendar with the solar year.

Blasing, an archaeologist with the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation's Oklahoma-Texas Area Office, has taken a special interest in looking at the intimate relationship Native Americans saw between celestial happenings and geographical landmarks. "zIt is a common Native American concept," he explains, "that certain features, such as camps, settlements and scred landmarks are arranged in the same pattern as certain astronomical features, such as stars and planets. Therefore, specific geographic features are identified with specific astronomical features. The relative locations of these celestial features are mirrored on the face of the earth, just like features are reversed when we see something in a mirror."

Blasing, an archaeologist with the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation's Oklahoma-Texas Area Office, has taken a special interest in looking at the intimate relationship Native Americans saw between celestial happenings and geographical landmarks. "zIt is a common Native American concept," he explains, "that certain features, such as camps, settlements and scred landmarks are arranged in the same pattern as certain astronomical features, such as stars and planets. Therefore, specific geographic features are identified with specific astronomical features. The relative locations of these celestial features are mirrored on the face of the earth, just like features are reversed when we see something in a mirror."

Because Blasing's research ideas are so closely related to Blakeslee's, about a year ago Blakeslee invited Blasing to write several chapters for his book. "It has been great collaborating with Don on this project," Blasing says. "I like the way he looks at large-scale patterns of culture, as opposed to concentrating on a given archaeological site or cultural group. When he was my graduate advisor, we both developed a strong interest in — and started sharing ideas first on trails and then on — Native American astronomy and religion."

Red Star

Astronomy has been fascinating to Blakeslee since junior high school, and early on during research pursuits in his chosen academic specialty he took an interest in how Native Americans looked at the sky, mapped the movements of its celestial bodies and incorporated that knowledge into their religious stories, rituals and lives. For instance (and to oversimplify), the Plains Pawnee built their earth lodges as models of the cosmos. Traditionally, the roof of the lodge was supported by four corner posts, each representing a direction, a color and a specific star. As the posts supported the roof, the four "directions" were seen to hold up the dome of the sky.

Heavenly events are also at the core of the Pawnee's creation myth, which, in brief, relates that the Morning Star in the east must find and overcome the Evening Star in the west so that creation might be achieved. Blasing explains further, "The Pawnee called Mars 'Morning Star.' As we view them in the sky, the stars remain in the same position relative to one another. The planets rotate around the sun, so they appear to gradually move around the sky relative to the stars. In the creation story, there is a council held in the eastern sky. After the council, Morning Star sets off on an epic journey, where he has to overcome a series of adversaries. In watching the sky during the approximate two-year orbital cycle of Mars, several planets come together. After this, Mars moves gradually higher in the sky, passing several stars and constellations, which are known to represent animals to the Pawnee. These stars and constellations appear to be encountered in the same order as the animals they represent are overcome in the creation story, making it likely the story describes actual sky events."

Most scholars writing before Blakeslee and Blasing emphasize the differences among Native American astronomies and cosmologies. But Blaskeslee and Blasing stress just the opposite: the similarities, which, they argue, demonstrate the widespread connectedness of Native American life.

White Star

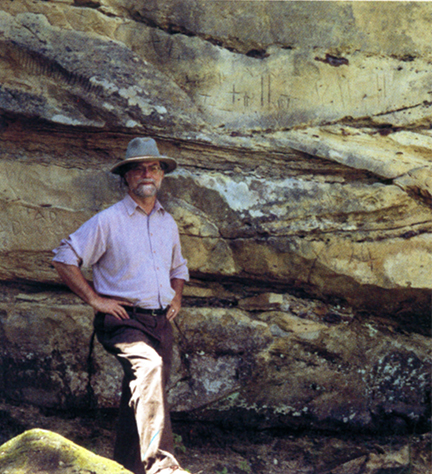

Certain sacred sites, they explain, share a unique complex of natural features, including a cliff, a dome-shaped hill, water, often trees and a cave or other type of opening into the underworld. Blakeslee was explaining those features to a civic group in Greensburg, Kan., several years ago when he noticed two people in the back of the room becoming more and more excited. "From Texas to Alberta," he told the group, "the natives of the Plains made pilgrimages to sacred sites. These included natural features such as Colorado's Manitou Springs, Nebraska's Guide Rock and meteorite fields in Kansas."

After he had finished his presentation, the couple approached him. They wanted to show him a site near where the Brenham Meteorites had been found. "When I saw the site," he recalls, "there was no doubt. This is connected with the Brenham meteorite-strewn field. This is the sacred place closest to it. It has all he features typical of a place where people can communicate with the spirits that live in the underworld. And the pictures there clearly represent a falling star and people with stars in their hands."

After he had finished his presentation, the couple approached him. They wanted to show him a site near where the Brenham Meteorites had been found. "When I saw the site," he recalls, "there was no doubt. This is connected with the Brenham meteorite-strewn field. This is the sacred place closest to it. It has all he features typical of a place where people can communicate with the spirits that live in the underworld. And the pictures there clearly represent a falling star and people with stars in their hands."

Because metallic meteorites, like the unique spirals of fingerprints or DNA, can be identified conclusively, scholars know the Brenham Meteorites were transported to burial mounds in Ohio, thus demonstrating a far-reaching Native American communications network. But such physical proof is not the only line of evidence Blakeslee has found to show not only how important meteorites were to Native Americans, but just how long ago they had woven their communications web.

Black Star

This summer Blakeslee spoke with a linguist about some of his research ideas and learned that the words for "metal" in Native American languages are, he explains, "not what you would expect. They all seem to have had a word for 'metal' in general, and then they added descriptors when referring to iron or silver or copper. What this linguist ran across is that in most of the languages he was able to record for North America, the word for 'metal' is a lone word, is not native to the language, but is not borrowed from European languages. And it's prehistoric. This brings up the possibility that something happened so that everybody on the continent began to talk about metal at the same time, and the word spread, apparently, from one place."

Blakeslee doesn't know what that "somehting" is or where that "one place" is located, but he's planning on working with meteorite specialists to investigate a mysterious and very sacred site in Yellowstone Park. He doesn't know how old the Native American word for 'metal' is, but he's looking forward to narrowing down the time of origin with the help of linguists.

He does, however, know what the general argument of his book will be: "The little bit we know about the Native American intellectual tradition suggests it ought to be given status equal to that of the intellectual traditions of the Old World — that it's not different in kind from those of India, China and Europe." And he knows the title: The Celestial Mirror.