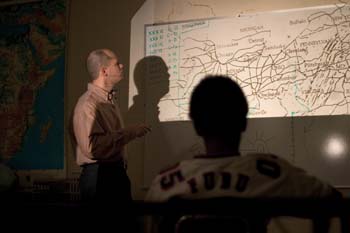

Patrick Audley fs ’93. Audley has taught for 28 years, including 11

years at the ranch.

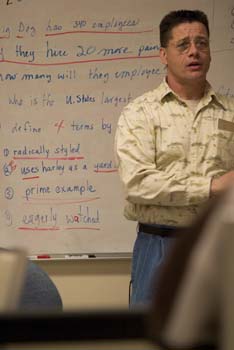

The bell rings at 9:55 a.m. Steve Holbrook ’00/04 welcomes six students, all at-risk teenage boys, to his U.S. history class at Judge Riddel Boys Ranch near Goddard, Kan.

Armed with a classroom array of books, posters and the transparencies of an overhead projector, Holbrook begins his lesson about 1840s education and health reforms, “Towards a Better America.”

“I can smell the rightness in that answer,” Holbrook responds after listening to a student’s first attempt at defining democracy. “But it’s not quite there.” The thought behind the classroom discussion is projected on the blackboard: “In order for democracies to work efficiently, people must be educated.”

Holbrook’s 11 years of teaching — all at the boys ranch — have equipped him with the facility to cover lessons within lessons. Today, for instance, he not only points out that “back in 1840, only about 1 percent of the U.S. population voted,” but also tosses out pointers on notetaking, how to use maps and the importance of eye contact.

He works hard to make his subject matter directly relevant to his students. “If you can read and write, you’re more capable of controlling your world,” he says, at first focusing his explanatory comments on what this meant for Americans of the 1840s. After surveying the beginnings of formal education in the United States, he brings his audience back to the present: “Today, we live in a world where education is demanded.”

He asks, “How many of you plan to graduate from high school?” All but two raise their hands. The conversation continues, touching on GEDs and trade training. A student mentions “working in concrete,” which sparks far-ranging talk about future job options.

Holbrook listens, then rounds up the conversation: “That’s a young man’s job. You can rely on your speed and strength right now, but if you don’t get an education, you’ll have to rely on your body all your life. As time goes on, more times you have to rely on your mind.”

“Yeah, a better education gets you an easier job,” contributes one student.

“Not easier,” Holbrook prompts. “Get that out of your mind.”

“Okay, less physical.”

“That’s it.”

Down the hall in a large classroom with windows opening onto a picturesque view into the ranch’s 67 wooded acres, Patrick Audley fs ’93 works individually with students studying for General Educational Development testing.

A veteran teacher with 28 years of experience, Audley, like Holbrook, has taught at the ranch for 11 years. “I’ve been in charge of GED instruction since April of 2004,” he says. “I’m most proud of the success rate. Out of 35 students tested, 34 have passed.”

The six students in Audley’s class study at their own pace. All but two are working on computers. Some focus on science; others English. One is writing an essay. Audley moves from student to student, prepared to assist with any problems they might encounter in math, reading, language arts, writing, social studies and science.

Inside the other ranch classrooms, Kay Clark, Craig Moore, Russell Thayer fs ’99 and Dennis Thomas ’73/84 are covering their subjects: English, science, math and computer lab, respectively.

After the 10:50 a.m. bell rings an end to the ranch’s second class period of the day, Holbrook, who, in addition to teaching social studies, serves as lead teacher and building administrator, sits down in his office to prepare for his next class.

He says, “Our classrooms are a little like the early American model — one room, one teacher, all different ages of students functioning at different levels. Nine out of 10 students, maybe nine and a half out of 10, who come through here are great kids, not at all like what this place is known for outside of this place.”

“Don’t much like it here, too many rules. All I did was steal a bike.”

Located on 67 wooded acres southwest of Lake Afton Dam, the boys ranch is 23 miles from downtown Wichita. In addition to the main building, the ranch has a gym, a Job Readiness Training workshop, hay barns and stables. Its grounds feature a garden, a baseball field, nature trail, volleyball pit, a swimming pool and pasture for riding and exercising the ranch horses.

“We have lots of deer and turkey around here,” reports R. J. Brassfield ’72, the ranch’s facility manager and program director whose experience with at-risk juveniles began in 1969.

and proper social behavior, the most challenging

aspect of working at the ranch is getting out of bed

in the morning,” says Steve Holbrook.

He explains, “While attending WSU on the G.I. Bill, I volunteered to work with kids in the Wichita Anti-Poverty Program in Planeview, Kansas. I grew up in Planeview, and this is where my family still resides. My part-time job quickly became a full-time career in human services."

A boys ranch administrator since 1995, Brassfield relates that while classroom operations are run under the authority of Wichita public schools, the correctional facility and its various rehabilitation programs are the responsibility of the Sedgwick Co. Department of Corrections, Youth Services. “I don’t know of a better equipped, staffed or supported facility anywhere in the region,” he says.

The ranch serves boys from the ages of 13-17 in need of a second chance. Brassfield explains that ranch residents have been ordered into the state’s custody for placement outside their homes after being found guilty in juvenile court of offenses that range from misdemeanors followed by breaking probation to convictions for such person crimes as aggravated robbery, aggravated assault and aggravated burglary.

The correctional facility, which operates continuously at its licensed capacity of 49, provides individual, group, family and drug and alcohol counseling, GED and regular school education, employment training, paid work experience and community reintegration assistance. Each resident has an individual treatment plan, and services are tailored to that individual’s needs. The facility is not locked, but the youths are under 24-hour supervision.

“I broke probation, so they sent me here. I’m working on getting a GED. Right now, I’m studying for the science part.”

Established in 1961 under the direction of juvenile Judge James V. Riddel ’37, a University of Wichita political science graduate, the ranch was first called the Lake Afton Boys Ranch. According to ranch history, its original mission was to provide a “home away from home” for boys ages 6-16, many of whom had become involved with the juvenile court because of truancy or “waywardness.” After the judge’s death in 1982, Sedgwick Co. commissioners renamed the ranch in honor of him.

Through the years, the ranch’s purpose has matured. As Robert Coleman, who coordinates the ranch’s academic operations, explained in 2000 when invited to speak at a conference organized by the Center for National Policy, “The purpose … is to remove children from the environment where they had problems in an attempt to reshape their values and beliefs and help them set goals.”

The CNP conference was set up to explore the effectiveness and potential replicability of a small number of program approaches for juvenile offenders. All selected programs, including Judge Riddel Boys Ranch, were found to be organized around innovative combinations of discipline and education. The information shared at the conference was assembled into the 2001 report New Programs for Youth Offenders: A Search for Effective National Models.

In the foreword to that report, former Congressman Leon Panetta (D-CA) and former Congressman Rod Chandler (R-WA) wrote: “We must not give up on problem and offending youth: These are precisely the young people in whose improvement we must invest. As this cnp conference demonstrates, there are in fact successful ways to do so — models that cross the standard division between ‘left’ and ‘right,’ ‘liberal’ and ‘conservative,’ Democrat and Republican.

They therefore offer our nation an opportunity to build upon a rare social policy consensus — as well as upon a rare example of tested and proven success.

“We have, in short, the means to build a better future by bettering the young people who will inhabit — and can either contribute to or threaten — that future. It’s all a matter of what we value.”

“I like the job training you can get here. I like cars and want to be a mechanic.”

Male juveniles commit proportionately more than their share of crimes, and those between the ages of 15 and 19 commit the bulk of violent offenses, according to the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, which compiles arrest information provided by law enforcement agencies and every four years publishes a national report examining the trends, rates and statistics of juvenile criminal activity. OJJDP’s next study is due out later this year.

prepare students to take the GED

test. I’m most proud of the success

rate. Out of 35 students tested, 34

have passed," Patrick Audley says.

Roughly half of all youth arrests are made on account of theft, simple assault, drug abuse, disorderly conduct and curfew violations. OJJDP statistics show theft as the greatest cause.

In 1999, some 2.5 million juvenile arrests were recorded; of these, 380,500 were for theft. In 2000, there were 2.4 million arrests, 363,500 of which were for theft. Drug abuse violations accounted for 198,400 of the 1999 arrests and 203,900 of the arrests in 2000. In 1999, there were 103,900 violent crime arrests, while 98,900 arrests were reported in 2000.

At the ranch, roughly half of the youth residents are “in custody for misdemeanor offenses, after they have failed standard probation and intensive probation in the community,” Brassfield reports. “The other half are felony offenders. Our youth are typically very far behind in their education. Many need outpatient substance abuse treatment, mental health care and counseling to address criminal behavior, anger management, empathy, grief and family issues.”

“Yeah, I like it here okay. They’re teaching me a lot of things. I’m pretty good in science, so I’m looking into how to get into college to study that more, after I get out.”

Brassfield and other juvenile correctional experts have found that effective rehabilitation is often grounded in structure and discipline — in rules, norms, standards, expectations, rewards and punishments set by family members and other support networks that many juvenile offenders lack.

And education, he stresses, is central to the process: “When the joy of learning takes root, often for the first time, it makes a profound change in a boy’s life. Therein lies the power of education to secure the blessings of opportunity and freedom from poverty for anyone willing to work hard enough.”

One of Brassfield’s many duties is conducting program-completion and recidivism reports. His review of records through Dec. 31, 2004 for juveniles admitted to the ranch during calendar years 2000 through 2003 shows several impressive outcomes. During those years, juvenile residents successfully completed the program at an average rate of 82 percent, with a low of 75 in the year 2000 and a high of 87 percent in 2002.

The percentage of youths who, after successfully exiting the program, did not engage in new unlawful behavior resulting in a guilty finding in the 18th Judicial District Courts, either juvenile or adult, stands at 90 percent six months out, with a range of 88 to 95 percent from the years 2003 and 2000, respectively.

At 12 months, the post-release success rate averages 75 percent, with a low of 72 percent in 2001 and a high of 78 percent in 2002.

“Overall,” Brassfield says, “the data demonstrates our residents are experiencing success at completing the program — and behaving lawfully when they return home to live in the community.”

He continues, “The constant challenges here at the ranch are the kinds of problems and concerns that bring kids here in the first place, and then beyond that, managing the anticipated behaviors to maintain a safe, secure and open treatment environment. Sustaining the progress of the individual youth who is helped in countless ways from the examples set by staff, teachers and counselors is a high priority.”

“The food’s not so good, but I like the people — they treat you good. I’m interested in going on to college, maybe studying criminal justice.”

The ranch’s success in helping its resident students is an obvious point of pride with Brassfield, who praises the more than 50 ranch employees who share his and the ranch’s mission.

“The staffs at the ranch, both school and county,” he says, “work hard to become skilled care providers of juvenile behavior management services — without the use of conventional detention restraining aids such as mace or handcuffs or weapons of any kind. It’s hard work, but highly rewarding. It’s equally fulfilling to see the kids from the neighborhoods complete the ranch program, return to their homes and schools and continue to be successful.”

Holbrook echoes the thought: “Personally, I believe student success at the ranch boils down to confidence that each student has the social and educational tools necessary to reintegrate into school and into the community. The most rewarding aspect of working at the ranch is by far the exit interview with each student. The sincerity of the conversation, the eye contact, listening to their plans and dreams, the handshake — it always makes for an energizing moment.”

Audley adds, “There’s satisfaction in knowing we’ve made dramatic changes in some lives.”

“You have to think about things here — like having goals and what you’re going to do later in life. I’m thinking about getting a job and someday starting a family.”

Holbrook says multiple experiences at WSU prepared him well for his job at the ranch.

He mentions a strong appreciation for his history professors, especially associate professor Judy Johnson, as well as the benefits of completing a master’s degree in educational administration and supervision, which taught him, he says, “the precision of thought necessary to communicate with a variety of audiences.”

Holbrook enjoys his variety of audiences at the ranch. This is obvious from two things in particular: He’s never taught anywhere else. “There happened to be an opening at the ranch in 1994,” he recalls. “I first interviewed with USD 259, and this was my first job, my only job. I’ve cut my teeth at the ranch. Maybe I’ll stay until all my teeth are gone!”

And his outlook: “My upbringing mirrors that of my students in that education was not important to me as a young person. I now help students make choices about education that I did not. Besides convincing students of the value of education and proper social behavior, the most challenging aspect of working at the ranch is getting out of bed in the morning. Once I’m in the building, every day is a good day.”

Today, as the end of the third class period nears, Holbrook wraps up his history lesson, nods to his students and switches off the overhead projector.

“Okay, gentlemen, I’ll see you tomorrow.”

on the ranch. Wichita State graduate R.J. Brassfield ’72,

is facility manager and program director, and graduate

Glenda Martens ’94/04, is the residential coordinator.

Shocker Ranch Hands

Judge James V. Riddel Boys Ranch, a residential corrections school near Goddard, Kan., serves juvenile boys from the ages of 13-17 who have been ordered into the state’s custody for placement outside their homes after being found guilty in juvenile court of crimes ranging from misdemeanor offenses followed by breaking probation to convictions for such person crimes as aggravated robbery, aggravated assault and aggravated burglary.

The boys ranch, which in 2000 was selected by the Center for National Policy as a national model of effective juvenile offender programming, is a public agency operated by the Sedgwick Co. Department of Corrections.

The school at the ranch is operated under authority of the Wichita public school district and overseen by school coordinator Robert Coleman. USD 259 teachers at the ranch who are WSU-educated are Patrick Audley fs ’93, GED/Title 1; Steve Holbrook ’00/04, social studies, lead teacher, building administrator; Russell Thayer fs ’99, mathematics; and Dennis Thomas ’73/84, computer lab.

On the county side, John Ayres, corrections worker; R.J. Brassfield ’72, facility manager and program director; Stacy Cotten ’98, independent living therapist; Ken Cox fs ’96, corrections worker; Willie Davis ’02, corrections worker; Sandra Duffield ’78/90, program coordinator; Kevin Hansen ’96, independent living therapist; Floyd Johnson ’99, corrections supervisor; Shaun Johnson ’03/03, corrections worker; Julie Leonard ’98/00, senior corrections worker; Glenda Martens ’94/04, residential coordinator; Kami Ochs-Thatcher ’02/03, corrections worker; Rodney Pelly ’99, corrections worker; Jimmy Santiago ’02, corrections worker; Gary Sutton ’80, senior independent living therapist; Phil Tennison ’02, corrections transporter; and Kitty Triebel ’80, corrections supervisor, are all on staff.