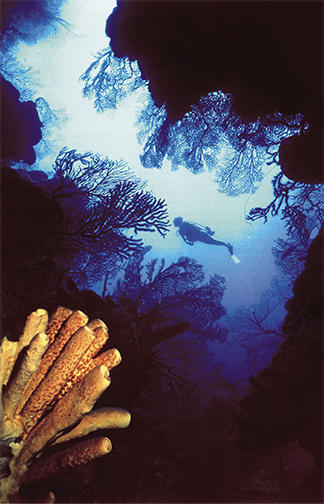

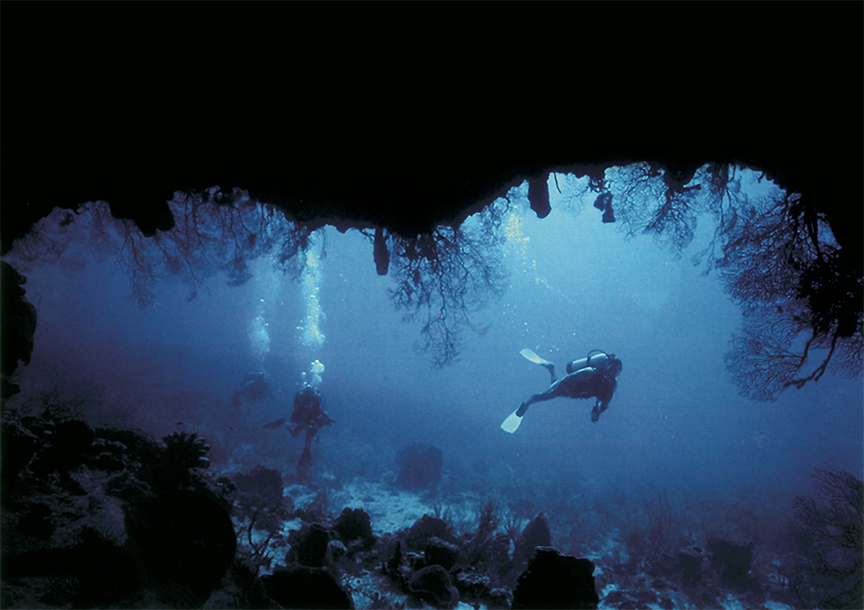

Earth’s oceans deep echo with mystery, their exotic beauty luring explorers to lifetimes of study.

“The first time I stuck my head under water in the Florida Keys, I thought, ‘I don’t believe how beautiful this is,’” says author, publisher and marine photographer Paul Humann ’61/61.

Although Humann showed an interest in water sports throughout his formative years, he adds that he always felt more drawn to the mountains than the ocean.

But that first dive and his subsequent explorations of the sea and its many mysterious inhabitants have played an integral role in his life.

When Humann took his first dive, circa 1961, the sport had not yet peaked in popularity — in fact, there were few, if any, SCUBA certification programs. Naturally, his friends back in landlocked Kansas were fascinated by what he saw below the surface of the water.

So on his second trip, he rented a camera so he could take simple snapshots. The results, he remembers, were “nothing special,” but later, after he’d purchased his own camera and become more practiced at photography, the results were superior. Humann remembers, “People would say, ‘Oh, you should be in National Geographic.’ Well,” he adds, “I knew I wasn’t that good.”

He was good enough to land photos in Skin Diver magazine, one of the few publications of its kind in the United States at that time. But neither diving nor photography was paying his bills. He’d taken a law degree after his graduation from Wichita State and set up an office in Wichita.

Quincalee Brown '61, president of QB Enterprises, McLean, Va., and Humann’s University of Wichita Debate Squad teammate, recalls, “Paul joined the university’s Debate Squad our junior year. He was generally quiet and soft spoken, but was also smart, fast on his feet and had ability for quick thinking and hard analysis. The kinds of skills taught by debate — logical analysis, the ability to communicate substance well and an ability to read an audience — are obviously ones that would relate to his law career.

I also contend that the innate abilities learned by that fast and critical analysis served Paul well in his later career as an underwater diver and photographer. Everything we do in life is additive — and my guess is that the skills learned from debate have added to Paul’s ability to fully realize his dreams.”

Although Humann excelled as a lawyer, after a time he found himself increasingly torn between his profession and his passion. “I was sitting in my office at First and Market one afternoon, watching the snow come down and said to myself, ‘What are you doing with your life?’” he recalls. “I enjoyed taking pictures a lot more than practicing law and thought I could be good at it if I gained more experience.”

At first he thought he would leave Kansas and buy a dive shop, most likely in Florida, then considered buying a dive resort before he realized that managing such an operation probably wouldn’t allow him to pursue photography to the degree he wanted.

californianus wollebacki, often entertain divers and

snorkelers in the archipelago. Paul Humann’s photo of

the playful marine mammals can be found in his and Ned

DeLoach’s 1993 book Reef Fish Identification: Galápagos.

Eventually, he settled on the idea of buying a boat, offering fellow enthusiasts diving tours on a small live-aboard craft.

He began saving money toward that end, not knowing exactly when he’d reach his goal but believing it would happen when the time was right. Then, something unexpected happened. A friend told him that there was a boat for sale in Grand Cayman, with all the necessary licenses already in place.

“Suddenly I was on an airplane to Grand Cayman Island,” Humann says, “where I talked to the boat’s owner and made a deal.”

But the deal proved anything but the end of his worries. He still didn’t have the money he needed. On a flight back to Kansas, he couldn’t help but wonder what he’d done: “I thought, ‘How am I going to pay for this?’ I basically begged, borrowed and stole from everybody I could –– parents, for instance — and eventually got enough money to close the deal.”

Humann moved to Grand Cayman, gave tours and dove up to three times a day, building his portfolio and reputation. He learned how to identify fish from more seasoned divers, a skill he knew he’d need. By the end of five years, though, he’d come to another roadblock.

Although he had plenty of subjects for his photographs and felt secure enough financially, he was far outside the main publishing and photography hubs. With some small reluctance, he sold his business, moved to Florida and began selling his photographs full time. “Sometimes,” he explains, “I didn’t know where the next mortgage payment was coming from, but I always seemed to survive.”

By the dawn of the ’80s, scuba diving had increased in popularity. More people were curious about marine life, but as the demand for information grew, the outlets for information remained virtually the same. Most guidebooks were written by ichthyologists and were rarely user-friendly.

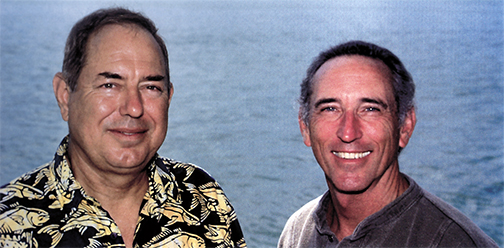

The books often charted fish according to presumed evolutionary order and separated photos from the text in such a way that the reader would need to flip constantly between the identifying features of a fish and a photo of it. Humann and Ned DeLoach, a former schoolteacher, decided to change that.

They agreed to form their own publishing house, New World Publishing, and begin releasing more user-friendly guides, guides that would help beginning divers increase their knowledge more quickly, guides that also would be printed in glorious, full color.

But as the duo began this new endeavor, Humann found himself in an all-too-familiar situation: “We didn’t have the money to publish a book back in those days. I did the same thing that I’d done when I bought the boat –– begged, borrowed and stole from friends. We second mortgaged our houses and got as much money as we could get from the banks. We figured that if we could have everything paid back in three years we’d be lucky,” he says, then adds, “The books were so successful that we paid everything back in six months.”

Organized so that divers begin specifically with what the fish looks like (fish with sloping heads and tapered bodies are kept in one chapter, for instance; those that are reddish in color with big eyes are in another), DeLoach and Humann’s ocean flora and fauna identification books have been consistent successes and are often considered required reading for divers and marine photographers alike.

Today, the New World series includes volumes about reef fish and reef coral, as well as volumes that cover coastal fish and other reef creatures.

The scientific community has also embraced Humann’s work, especially since his rediscovery of the “flashlight fish” (Kryptophanaron alfredi). The fish is responsible for what many people saw as “strange, green lights” emanating from coral reefs, where the creature lives in darkness, rarely making its way outside that secluded world.

The fish’s light comes from a bacteria-filled sac below each eye. This bioluminescence, scientists have noted, is similar to the kind that fireflies create.

But when Humann came across the fish in the 1980s, there were apparently only two documented sightings –– the first in 1918 when one was caught in a fishing net 600 feet deep and the other more than half a century later when one was reported floating dead on the water’s surface near Jamaica. “I’d never seen anything like it,” the photographer reports, adding that he contacted a friend at the Philadelphia Academy of Sciences, who asked him for more photos.

When photographs of the unique fish began to appear, Humann began hearing from a variety of people curious about seeing the creature for themselves. “The discovery stirred a lot of interest within the scientific community and ultimately the Philadelphia Academy of Sciences and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in California chartered a boat and came down with the sole purpose of capturing some specimens of it,” he reports. “Needless to say, I made good friends and they helped me in later instances.”

In the ’80s Humann was one of two dozen professional marine life photographer-writers globally.

He had begun his venture with DeLoach and published a book entitled Galapagos: A Terrestrial and Marine Phenomenon. But those achievements didn’t stop him from striving for even greater goals.

Today, he continues to dive on a regular basis, accumulating between 200-300 dives a year, provides tips for less experienced diver/photographers (you don’t necessarily need to go looking for shots, he points out, rather, if you wait and observe your surroundings, good shots often come to you) and works on environmental endeavors.

He is co-founder of the Reef Environmental Education Foundation, which, he says, “does for fish what Audubon bird watchers do for birds.” REEF enlists volunteer divers to take censuses of fish throughout the world and send those reports to REEF’s headquarters.

“The primary people using this are environmentalists but also the marine life management community,” he explains. “It gives them a real view of what’s going on with fish populations in the ocean, which may seriously impact the way that catch rates and seasons are managed.” Most important, he says, are REEF's overall goals of preserving marine life and protecting the ocean itself.

“The underwater world is the last remaining unexplored frontier on earth,” he notes. “There’s lots about that world that we don’t know yet. Underwater, with maybe the exception of what they’re finding in the treetops of some of the great rainforests, is the one place we haven’t studied fully. We’re making discoveries all the time — to dive and experience this is a very exciting thing.”

After all, no one yet truly knows all that is down there.