physical exams, order and administer tests, make

diagnoses and treat illnesses.

Physician assistants are relative newcomers to the world of medicine. Yet they have skillfully sutured a permanent place for themselves within today’s full circle of patient care.

“The doctors, the nurses, the technicians — we all see tragedies and mourn together,” says ER physician assistant Matthew Lockwood '97. “And we rejoice in our successes together.”

Some rare days the emergency department at Topeka's Stormont-Vail HealthCare hospital is nearly empty. Today is not one of those days.

Lockwood, a Wichita State-educated physician assistant, knocks lightly on the door of one of Stormont-Vail’s examination rooms.

Despite the patient board filled with names, the stack of core encounter forms listing the medical histories and current ailments of newly admitted patients — and the patients themselves who are waiting, sometimes impatiently, for his attention this Monday afternoon, his manner is calm; his pace, measured; attention, focused on the person on the other side of this door.

Inside, strapped flat on her back to a supportive board and a brace around her neck, is 46-year-old “Delores.” Her neck and lower back are the centers of her pain, the result of a car accident.

Lockwood introduces himself and begins his examination. He explains his every action and asks scores of questions, intent on not missing any important medical clue.

“Tell me what happened to you,” he says, leaning in closer to Delores to hear her answer. Without haste, but with no lost time, he completes his medical assessment, making sure her pain medication is adequate and that she’s as comfortable as possible, and walks back to the emergency department’s central station where he charts his findings and tells the unit clerk what X-rays and other tests to order.

He then reaches for the next top-of-the-stack core encounter form, reads it carefully and heads for the next door, the next patient. Today, he is making the rounds during a six-hour shift, from noon until 6 p.m. Tomorrow, he’s set to work 12 hours.

He knocks. Behind this door is 18-year-old “Brandon,” who was brought in to the emergency department after experiencing intense stomach pain during a morning auto class. After introducing himself — “Hi, I’m Matt. I’m Dr. (Douglas R.) Rose’s physician assistant.” — Lockwood immediately begins his medical detective work. “Did you eat anything this morning?”

“A cinnamon roll.”

The PA asks more questions and listens closely to the answers. He listens to the internal sounds of Brandon’s body with his stethoscope and then with his hands gently probes the region of pain, asking with every pressure, “Does this hurt?,” “Does it hurt here?”

As he completes his examination, he explains to Brandon that the problem may be a number of things, including gastritis or pancreatitis, and that in order to determine exactly what is causing the pain a series of medical tests will be ordered.

Sensitive to the glimmer of anxiety in Brandon’s eyes, Lockwood adds before leaving the room: “I promise I’ll be back to talk with you more about this.”

Then it’s back to the central station for charting and test ordering, a bit of bantering with his co-workers — and the next core encounter form.

St. Elsewhere

Like all physician assistants, Lockwood, who has worked a year and a half for Emergency Physicians of Topeka, a five-physician group that contracts with area hospitals for their services, practices medicine under the supervision of licensed physicians.

As a PA, he’s qualified to give physical exams, order and administer tests, make diagnoses and treat illnesses. He has been educated, in short, to provide many of the services that would otherwise be provided by a doctor. While he has opted for emergency-department work, PAs are found in nearly every medical and surgical specialty and health-care setting.

a minimum of 100 hours of continuing

education every two years and take a

written examination every six years. In

addition, they must meet state licensing

requirements.

Cecilia Backstrom ’90/90, for instance, has worked for eight years in Wichita’s Dermatology Clinic, where she sees on average 45-50 patients a day. She considers the most challenging aspect of her work to be detecting and identifying the almost infinitely varied dermatological markers of disease in order to make the correct diagnosis.

“There are so many differential diagnoses,” she says. “To a patient, a rash may just look like a rash, but it might be symptomatic of something much more serious. Everything is so specific, so targeted — in diagnosis, it’s the nuances that make all the difference.”

Formerly a respiratory therapist working in Hawaii, Backstrom was inspired to shift her professional focus after watching a certain episode of a popular TV show. “I don’t think I’ve ever told anyone this,” she says with a laugh.

“But remember that TV show, St. Elsewhere? One night they featured a guy going to PA school. Something about that captured my attention, and I sent away for information about PA programs.”

Since her husband was from Kansas, she looked into Wichita State’s accredited program and was pleased with what she discovered about the process of becoming and then working as a physician assistant in general and about WSU’s program in particular.

She learned that to practice, PAs must graduate from an accredited PA program and be authorized by the state or credentialed by the federal government. After graduation, PAs must pass a national certifying examination, which permits them to use the designation PA-C, meaning Physician Assistant-Certified.

To maintain certification, PAs must log a minimum of 100 hours of continuing education every two years and take a written examination every six years. In addition, they must meet state licensing requirements.

A PA for more than a decade now, Backstrom says the most rewarding aspect of her work is simply being able “to make people better. When they’re happy, I’m happy.”

General Hospital

The mission of WSU’s physician assistant department is to provide “a learning community dedicated to developing generalist health care professionals by valuing students; integrating teaching, scholarship, practice and service; and partnering with the community.”

Richard D. “Rick” Muma, associate professor and acting chair of WSU’s PA department, explains that Wichita State offers a four-year course of study that leads to a Bachelor of Science degree.

Study is divided into two parts: a 60 semester hour pre-professional curriculum, which includes requirements for general education as well as prescribed courses in the natural sciences, and an 81 semester hour (two-year) professional curriculum with a capacity of 92 students, meaning 46 students are accepted each year. More than 150 apply.

“The professional curriculum has two phases,” Muma explains. “The first-year phase is didactic and includes courses in the basic sciences — anatomy, pharmacology, physiology — and courses in assessment and management of medical problems.

The second-year phase is a series of clinical rotations in a variety of medical settings, primarily in Kansas. Students complete eight rotations of 5 to 8 weeks each, and all students must complete a minimum of three rotations outside the city of Wichita, with at least three in a rural or urban underserved community.”

Muma, who holds both a bachelor’s degree with a physician assistant major and a master’s degree with a major in community health education from the University of Texas-Houston and who is completing course work on a doctorate in higher education at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, is a passionate advocate for the PA profession.

“Physician assistants,” he says, “perform about 80 percent of what a doctor in family general practice performs. And studies consistently show that patients have a high level of satisfaction with PAs, who often spend more time with them explaining their medical conditions and treatment options. PAs make a huge difference, especially in areas that don’t have enough medical services and doctors.”

Wichita State student Jane Jittawait, who is in the first (or classroom) phase of the professional curriculum, is excited to have been accepted into the highly competitive program. “It’s very intense, very challenging,” she says.

“I came to WSU still trying to figure out what I wanted to do. As I took classes, I became more and more interested in the sciences, especially in biology and anatomy — and that led me into the health-care field. I believe God helped lead me to the PA program, and the door just opened.”

Of all the things Jittawait has gained from her educational experiences at Wichita State, it is the importance of humility that she forecasts will mean the most to her when she begins working as a physician assistant. “I’ve learned that no matter what you learn, even as you gain working experience in the field, there’s always more to learn,” she says. “Humility is key.”

Wichita State’s PA department, in the School of Health Sciences within the College of Health Professions, operates with the philosophy of preparing students “to function as generalists. It is the intent of the department that the education and training provided will prepare and encourage students to provide primary care in areas where the need is greatest.”

Emergency

After reading the next core encounter form, Lockwood makes arrangements for a female nurse to accompany him to the examination room in which 26-year-old “Chloe,” her husband and their youngest child are waiting. Chloe, who is 12 weeks into her fourth pregnancy, is suffering severe pain and bleeding. Everyone is concerned she will lose the baby.

Lockwood knocks lightly on the door and enters the room. He introduces himself to Chloe and her family and begins his series of questions, asking about fever and chills and when the bleeding began and what the pain feels like. “It feels like labor cramps,” she answers.

Her husband holds her hand tight as Lockwood begins a pelvic examination. He explains every move he makes as he daubs away the blood and continues with the exam. When finished, he reports that the cervix is closed, but that a blood test and a sonogram will provide a clearer picture of what is going on. As he takes his leave, he pauses to touch Chloe on her shoulder.

Back at the central station, he charts his findings, has Chloe’s tests ordered and then turns to the next core encounter form.

Waiting in the next examination room are 60-year-old “Lucy,” a high school Spanish teacher brought in because of nausea, slight dizziness and extreme fatigue, and her husband who sits close-by in a bedside chair. Lockwood greets them both and starts his questioning, working to narrow down the myriad of possibilities that might be causing Lucy’s complaints.

The PA checks her eyes and throat, listens to her breathing and continues with more questions, listening closely to her and her husband’s answers. He learns that Lucy has been feeling abnormally tired for a long time, that two years ago she suffered from a slipped disc, that when eating she “gets full too fast” and much more.

He absorbs the information, and when he finishes his assessment he tells the couple that anemia is a possible culprit, but for a more definite diagnosis, they must wait for the results of a number of tests, including a chest X-ray and blood and urine tests, which he is going to order now.

As he walks back to the central station, he says, “It’s difficult to diagnose chronic complaints. It’ll be interesting to see what we find out from the tests — or what we don’t find.”

As the afternoon ticks on, Lockwood continues his rounds. He meets 15-year-old “Sophie,” who passed out at school. Sophie tells the PA she doesn’t remember much about the episode, so after he completes his exam, he returns to the station to gather more details by calling the school nurse.

Then there is 87-year-old “Fred,” who was brought in from a nursing home where he had vomited blood. Suffering from dementia, Fred can’t answer Lockwood’s questions, but Fred’s sister, who has accompanied him, provides answers as best she can.

Back at the station, the PA has blood and urine tests ordered for Fred. He sees that the results are back from a few of the tests ordered earlier.

Although Brandon’s test results are not in yet, Lockwood goes to see him, as promised. He then returns to the central station to call an obstetrician about the results of Chloe’s tests. The doctor and the PA talk, but they’re up against the limits of medicine. “There’s nothing we can do,” Lockwood says. “There’s no medication we can give to stop the miscarriage.”

That is the worst part of his work. “The stress of the emergency room is difficult,” he says. “The environment is inherently chaotic. You never know what’s going to happen.”

Delores’ X-rays are in. After the emergency physician on duty studies the ghostly solid picture of her spine, Lockwood heads back to her room to tell her the news. “Your X-rays are normal,” he reports with a smile.

“But tomorrow you’re going to be extremely stiff. Hot baths and a gentle massage may help.” He re-examines her neck and the back of her head while he talks to her in detail about the pain medication he has prescribed. He gently rubs her arm as he tells her she can go home as soon as someone can come for her. Delores looks him in the eye and doesn’t need to vocalize the word, thanks.

“Nothing is more rewarding than helping people — than being able to make some order out of the chaos of the emergency room,” Lockwood says. “It feels so good to know that you can walk into an environment like that, focus your energies on someone who is very ill and help them feel better.”

And he heads for the next door.

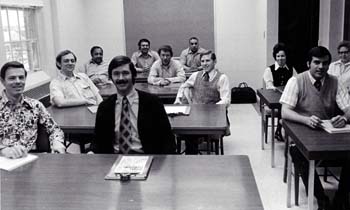

dark-haired woman at right in the back of the

classroom is Marvis Lary, who served as chair

of the university’s PA department from 1989-2001

and is now associate dean of WSU’s College of

Health Professions.

A Venerable Program

The first physician assistant educational programs were begun in the mid-1960s to offset a shortage of doctors. In 1972, the year Wichita State’s PA program began, there were fewer than 1,500 practicing physician assistants.

Today there are more than 45,000 PAs working in the United States — approximately 400 of them in the state of Kansas.

Its development spearheaded by Dr. D. Cramer Reed ’37, now retired from a distinguished career in medicine and in education, WSU’s program is the only PA program in Kansas and one of approximately 130 programs in the nation.

Accredited by the Accreditation Review Commission on Education for Physician Assistants, the program grants a Bachelor of Science with a major in Physician Assistant Studies.