Whitney ’31 (below) as they appear in the 1931

edition of Parnassus. As a University of Wichita

student, Whitney worked with Lieurance both on

campus and on the road when she performed as

a violinist for the WU strings ensemble.

During her 98 years, musician Isobel (Nevins) Whitney ’31 has played countless symphonies and suites, but she remembers one piece particularly from her years as a violinist with the University of Wichita orchestra and strings ensemble.

“‘By the Waters of Minnetonka,’ of course,” says Whitney, who lives in Wichita. “We were always sure to play that because it was Dean Lieurance’s favorite.”

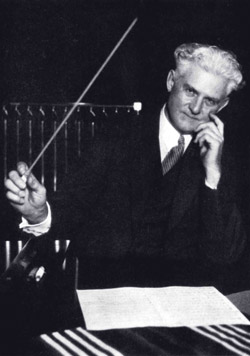

Thurlow Weed Lieurance (1876-1963), who served as the first dean of fine arts at WU, enjoyed conducting “Waters” for good reason — it was his own composition, and it remains his most famous.

Composed some 15 years before his arrival at WU in 1927, the “Indian Love Song” helped establish his national reputation as a composer and made him something of a local celebrity when he and his wife, mezzo-soprano Edna Wooley-Lieurance, arrived in Wichita.

Although sources differ in the specifics, the story of how Lieurance came to compose “Waters” is as fascinating as this American music standard’s own history. Inspired by recordings he made on the Crow Reservation in Montana in 1911, the piece is a product of its time, when American artists were beginning to discover the richness of Native American cultures.

Dancer and choreographer Martha Graham (1894-1991), for instance, was mining American Indian ceremonies for her modern dance works in much the same way as Lieurance was using American Indian sensibilities and instrumentation in his compositions.

The occasion for Lieurance’s trip to Montana was a visit with his brother, an Indian Service physician. (Others say it was a visit with an uncle.) Whatever the case, Lieurance met an Oglala Lakota Sioux singer named Sitting Eagle who was living on the Crow Reservation.

Sitting Eagle agreed to be recorded performing a traditional Sioux love song. Lieurance later described this moment as the turning point of his career: “That night marked an epoch in my life, opened to me a new world. What work I have since done has been due chiefly to that song.”

Lieurance secured his place in music history by marrying traditional American composition with Native American music and by introducing native instruments into the international music community. Flutes especially seemed to catch his attention, and many of the native flutes he collected are on permanent display in WSU’s music library located in the Duerksen Fine Arts Center. (The music library is named for him.)

His recordings of Native American music are housed in the Library of Congress; his papers can be accessed in Special Collections at WSU’s Ablah Library, and students of music history will find his scores and related materials at hundreds of public libraries and research institutions as far away as the National Library of Australia.

Lieurance achieved considerable popular success with “By the Waters of Minnetonka,” which was performed by the most prominent vocalists of the early 20th century, including Ernestine Schumann-Heink, Nellie Melba and Lieurance’s wife, who performed in costume as “Princess Watahwasso.”

The song appears on the soundtrack or as part of the score of four movies, including the 1944 Esther Williams vehicle Bathing Beauty. And musicians as diverse as Slim Whitman, Jimmy Wakely and Glenn Miller have recorded the tune. “The work itself is a perfect vehicle for interpretation,” Lieurance once said. “It just seems to roll on when it’s played — it’s a perfect vowel.”

Lieurance composed a number of similarly inspired songs, although none became as famous as “By the Waters of Minnetonka.” Sadly, when Fairmount Hall burned down early in his WU career, many of his original notes and recordings used for this series of compositions were lost.

Lieurance continued to compose during his tenure at WU, where he was beloved by many students. (The 1931 Parnassus is dedicated to him.) Isobel Whitney recalls that he took great care in auditioning prospective members of the orchestra and ensembles, “so we all ended up playing the same notes.”

Long before Duerksen and Wiedemann Recital Hall, instrumental musicians made do with Henrion Gymnasium for a practice space. Whitney remembers that Lieurance’s attitude mirrored the surroundings: “He was very casual during rehearsals,” she says, which put the students at ease.

Whitney, who earned an English degree with a math minor, continued to play and perform after her graduation until problems with her eyesight ended her favorite avocation. But she likes listening to classical music — “still my favorite” — and enjoys recounting key memories of her time at WU.