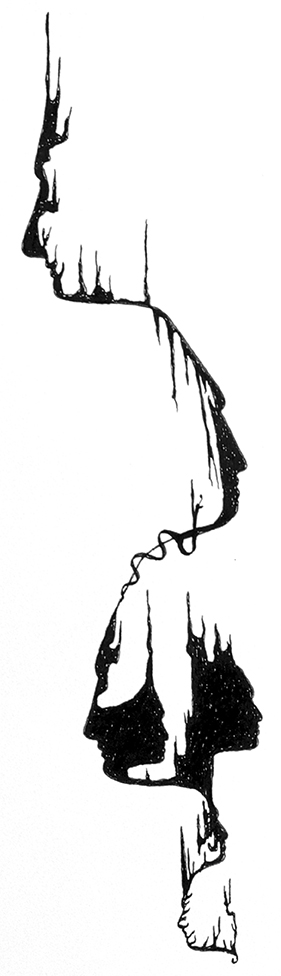

painting. This is "Blacksilver Waterfall: Sonata for

Bruce Conner," courtesy Emprise Bank Collection.

It’s his pet hawk, of all things, the hawk is black as night and sits there on his shoulder pecking nastily at a clunk of hamburger he holds up to it — In fact the sight of that is so rarely poetic, McLear whose poetry is really like a black hawk, he’s always writing about darkness, dark brown, dark bedrooms, moving curtains, chemical fire, dark pillows, love in chemical fiery red darkness, and writes all that in beautiful long lines that go across the page irregularly and aptly somehow — Handsome Hawk McLear.

– Jack Kerouac on Michael McClure (Pat McLear) in Big Sur

Like a hawk — poet, playwright, essayist, lyricist, novelist Michael McClure fs ’52 hunts his literary prey with a sharp eye, a far-listening ear and a gut-level wakefulness to life’s universe of ever-shifting shapes and sounds.

Mole-like, he burrows gene-deep through the velvety substrate of his own interior landscape. Lion-like, he roars and purrs his angers and pleasures on the page with feline grace, fury, playfulness and power.

And — notwithstanding Kerouac’s earlier assessment — Handsome Hawk McClure writes more or less equal measures of darkness and light.

The author of more than 20 volumes of poetry, more than 20 plays, several collections of essays and two novels, McClure is one of the most productive and inventive figures to emerge from America’s Beat movement, a strangely soothing yet deeply unsettling revolution in art, manners and consciousness that five decades ago began tearing apart accepted definitions of what constitutes literary art and, on a broader plane, what man is and should be.

One of five poets to participate in the event that ushered in the Beat Generation (the 1955 Six Gallery reading in San Francisco where Allen Ginsberg read his groundbreaking poem “Howl”), McClure is an environmentally focused writer who seeks to remind us we are mammals, animals — “creatures of Meat and Spirit,” as he writes in Meat Science Essays (1963).

Rediscovery and redefinition of man’s place in the natural world are necessary because, as he explains in his 1982 essay “Mozart and the Apple”: “WHEN A MAN DOES NOT ADMIT THAT HE IS AN ANIMAL, he is less than an animal. Not more but less.”

McClure lives in California with his wife, the sculptor Amy Evans McClure. About his poetry and its purpose, he says, “Perhaps my poetry is to broaden my sensorium, and hopefully it will broaden the sensoriums of other individuals who read it. In other words, the function of poetry, as I see it, is to create a myriad-mindedness.”

Toward that end, McClure has always been innovative. He introduced his beast language — a poetic vocabulary of roars, growls, grunts and howls interspersed with human speech — in Ghost Tantras (1964).

He wrote the Janis Joplin hit “Mercedes-Benz,” was literary mentor to Doors singer Jim Morrison and continues this musical collaboration by performing his poetry to the piano accompaniment of keyboardist and composer Ray Manzarek.

It was McClure who first called Bob Dylan “The Poet’s Poet” in an article for Rolling Stone.

His plays, notably The Beard, a discourse between Billy the Kid and Jean Harlow, have earned him underground fame (and censorship battles), while his Scratching the Beat Surface (1982) is the first book-length account of the Beat period written by a member of the movement.

Born in Marysville, Kan., in 1932, Michael, whose parents divorced when he was 5, split his childhood years between land-locked Kansas and the ocean shoreline and rain forests of the Pacific Northwest, where his maternal grandfather, a physician and amateur naturalist, fostered in him an interest in the natural world. After his mother’s second marriage, the 12-year-old returned to Kansas, to Wichita.

Drift

“I met Mike when we were eighth-graders at Robinson Junior High,” says Lee Streiff ’55, a retired educator. “Our early interests were science fiction and biology. Mike was into tropical fish. We spent hours in the country catching lizards and snakes — everything we could get our hands on. We kept detailed records of the animals.”

McClure’s “Memories from Childhood” (Fragments of Perseus, 1983) looks back to those years and shows, as Rod Phillips, assistant professor of writing and American culture at Michigan State, points out in his book, Forest Beatniks and Urban Thoreaus, “an early awareness of a clash between the human and non-human worlds”:

I REMEMBER THE FIELDS

of Kansas and the laws

that made

them flat and bare

I know when and where

the field mouse died.

I watched the rivers tried

for treason,

then laid straight,

and the cottonwood and opossum

placed upon the grate

of petroleum civilization!

“What first drew me to McClure’s poetry,” says Phillips, who also authored a monograph on McClure published as part of the Boise State University Western Writers Series (2003), “was his radical stance in regard to nature. He was one of the first American poets to not merely celebrate the beauty of the natural world, but to defend it.”

Streiff remembers that McClure began writing poetry in ninth grade. While their boy-scientist fascination with nature continued, their fields of inquiry expanded; literature and philosophy became important.

“We were always interested in ideas,” Streiff says. “I was drawn more to logic, Mike to myth. We read Nietzsche, for instance, but I liked Beyond Good and Evil, and he liked Thus Spake Zarathustra.”

As a teenager, McClure taught himself to write sonnets, sestinas and villanelles. The works of the visionary poet William Blake held special significance for him, but Percy Shelley, William Butler Yeats, Ezra Pound and Kenneth Patchen, among literally dozens of others, could also be found on his reading list.

While at East High School, McClure, Streiff and a small group of other similar-minded students became increasingly interested in art and music. They also tried to see clearly the realities of the socio-political environment in which they lived.

“I’m afraid,” McClure writes in Lighting the Corners: On Art, Nature, and the Visionary (1993), “that many people today that were not alive in the 1950s have a vague idea of what the ’50s were like. This was the period of the Cold War — you can imagine Bob Dylan as a 12-year-old boy watching the McCarthy hearings on television.”

Art historian and independent curator Jim Johnson ’75 describes the times this way: “With the post-World War II conversion to a consumer society, the American identity that we understand emerged with gusto. Defining characteristics such as ‘suburbia,’ ‘materialism’ and ‘conformity’ produced a Leave-It-To-Beaver identity spread by television and held dear by a largely white, educated middle class. But there were other forces at work — an alternative personality seeking another definition of American life.”

Susan Nelson ’54/79/80, WSU’s first instructor to teach a course on Black literature, recalls someone once describing Wichita as being “like popcorn. It’s so repressed, you’ve got to explode.”

McClure was drawn to the freer thinkers of the community, including local poet Irma Wassall, who was part of a circle of avant garde writers and artists that formed in Wichita in the 1930s.

Bud Norman, in a 1999 Wichita Eagle article, reports that Wassall “recited her poetry at the coffeehouses where the city’s most notorious bohemians hung out. Her young fans included a soon-to-be-noted counterculture poet named Michael McClure. ‘He brought me a whole notebook of poems and wanted my opinion, and I read the first page and told him he was going to be famous. He laughed, but he is,’ Wassall said.”

Many of Wichita’s “most notorious bohemians” found their way to the University of Wichita, as did McClure in the fall of 1950.

Straight Speech

“The Alibi Room in the basement of what’s today called Wilner Auditorium was where most WU students who were interested in the social part of university life went — students in good standing anyway,” recalls Don Ablah ’54. He adds, “I often went to Manning’s.”

Manning’s Lunch, located just off-campus at 1745 N. Fairmount, had a reputation for attracting WU’s more non-conformist students — those variously labeled bohemians, hipsters or beatniks. McClure, Streiff, David Haselwood ’53 and Bruce Conner fs ’53 were among Manning’s habitués.

“Looking back on it,” Haselwood says, “we must have seemed a little like exotic birds. You have to remember that the university’s Congregational ties were still strong. Dr. McKinley, who taught chemistry, still gave sermons in class. Our little coterie stood out in that kind of environment.”

When McClure first enrolled at WU, he selected three advanced English courses in addition to beginning English. He also signed up for military science, but dropped that class. During his years at WU, the English major studied the usual LAS subjects, botany and anthropology included, as well as art history, the principles of design and Greek — although, notes WSU registrar Bill Wynne drily, “Greek seemed to be Greek to him.”

Faculty members that Streiff recalls as favorites were Geraldine Hammond and Bill Nelson, both now WSU professors emeritus of English, plus English instructors Jo Ann (Sullivan) Rogers ’46/51 and Joan “Joanie” O’Bryant ’45/49. O’Bryant, who was killed in a 1964 car accident, was known for her folk singing and interest in folklore.

While at WU, McClure’s interest in art, abstract expressionism especially, deepened. He says, “I first saw Jackson Pollock’s work in a Life article. I first became aware of Motherwell, Rothko, Gottlieb, Tomlin and the group they represented in 1950 or ’51 when Bruce Conner brought them to my attention. It was a further revelation and expanded my earlier Pollock illumination.”

McClure and Conner reveled in the revolutionary works — McClure having glimpsed in their action painting a creative process that united body and mind.

“I think the way they painted, with their whole bodies, was the direction Mike was going in his writing,” Haselwood says. “‘Gesture’ is a word you see a lot in his poems. Their paintings are gestures out into space. Mike’s poetry is a gesture out into space.”

At WU, as elsewhere, the more bohemian students linked intellectual explorations with — partying. “We did some serious drinking,” Haselwood admits, adding with a laugh, “But how serious could that have been? The state was seriously dry.”

Streiff and Haselwood both remember McClure as an extremely good-looking guy who turned many girls’ heads. “When Mike was at a party, he would almost always be intensely pursuing a girl,” recalls Haselwood. At parties, Streiff says, “We argued, discussed, drank, read our poetry and played our music.” Haselwood: “What we talked about would go all over the place.”

Some of their talk centered on plans to produce a magazine that would showcase their art, both literary and visual. But misunderstandings and the subsequent squabbling among principal players, including Streiff and McClure, squashed the effort. (In 1996, Streiff and Conner finally put the Provincial Review into print, with original artwork, stories and even ads.)

This swirl of people who talked about art, literature and language, politics, poetics and their own latest works over coffee at Manning’s or beer at parties figures prominently in McClure’s autobiographical novel, The Mad Cub. Published in 1970, but written in 1964, it is his portrait of the artist.

The novel, writes Gregory Stephenson in “From the Substrate: Notes on the Work of Michael McClure,” is in many ways a “key to his work, providing an introduction to his concerns, his imagery and his vision.” The novel’s central image is that of a lion cub; its essential theme: human beings are mammals, a message that isn’t as simple as it may seem.

Stephenson notes, “It serves as the foundation of McClure’s vision. For the narrator, it provides a release from physical afflictions, from neurasthenia, alienation, despair and madness, and it represents the principal datum for a new orientation to his own life and the life of the world.”

McClure further strove to reconcile man-as-mind with man-as-animal in the poems of Ghost Tantras, written in his beast language. This, from “No. 99”:

GAHROOOOOM GRHH FARAHHRR OH THY /

NOOOSHEORRTOMESH GREEEEGRAHARRR /

OH THOU HERE, HERE, HERE IN MY FLESH /

RAISING THE CURTAIN

HAIEAYORR-REEEEHORRRR

in tranquility.

A few weeks into the new year of 1953, McClure left Wichita, heading first to New York City and then to the University of Arizona, where he met Joanna Kinnison, whom he later married and who shared his love of Thelonious Monk’s jazz and the writings of Federico García Lorca.

In 1954, he went to San Francisco, lured by Mark Rothko’s and Clifford Still’s painting classes at the San Francisco Art Institute. The painters, however, were no longer there, so McClure enrolled in poet Robert Duncan’s writing workshop at San Francisco State. It was Duncan who introduced him into the San Francisco poetry community and the coalescing Beat movement.

Exclamation

The year 1955 was a significant one for McClure: He married, met Allen Ginsberg and was asked to organize a poetry reading at a local art gallery.

in 1965. North Beach copyright Larry Keenan.

Too busy, he thankfully handed over organizational duties to Ginsberg. The event, the now-famous Six Gallery reading, was McClure’s first public reading. Among the four poems he read was “For the Death of 100 Whales.”

The event was a defining moment. About Ginsberg’s “Howl,” McClure later noted in Scratching, “In all of our memories no one had been so outspoken in poetry before — we had gone beyond a point of no return — and we were ready for it, for a point of no return. None of us wanted to go back to the gray, chill, militaristic silence, to the intellective void — to the land without poetry — to the spiritual drabness. We wanted to make it new and we wanted to invent it and the process of it as we went into it. We wanted voice and we wanted vision.”

McClure’s own distinctive vision was given voice in Hymns to St. Geryon (1959), the first major collection of his poems.

Hymns was published by Haselwood’s Auerhahn Press. Of McClure’s many works, Haselwood says, “I’m partial to Hymns. You can really see the beginning of Mike’s individual style.”

Two visually striking characteristics of McClure’s poetry first seen consistently in Hymns are his copious use of capital letters and lines of poetry that are centered on the page, thus creating shapes that resemble natural forms, as in this passage taken from Touching the Edge (1999):

DESPITE FASCINATION

DO NOT BE CONCERNED

That form is emptiness

And emptiness is form.

IT

IS

ALL

a brown

falling leaf

no different from

anything

else.

McClure’s grasp of imagery and a masterful use of repetition also inhabit Hymns, as in “Peyote Poem” when his thought “I hear / the music of myself and write it down / for no one to read” spirals back as “Writing the music of life / in words.”

The biological bent to his work, also evident in Hymns, caught the attention of none other than the elucidator of DNA’s structure, Francis Crick, who used two lines from “Peyote” to open his book, Of Molecules and Men: “THIS IS THE POWERFUL KNOWLEDGE / we smile with it.”

In 1959 McClure wrote about his mode of making poetry. In Scratching, he quotes from that writing: “A writing, if physiological, is an existent appendage of a total energy charge, not a compilation of formal variances but a direct (not virtual) manifestation of gene-deep feelings.”

He identifies four characteristics “in the morphology of my writing”: drift, straight speech, exclamation and the rose flush, explaining drift as “a temporary cessation, I pass, leaving the blankness on the page”; straight speech as “a lucid connection with my deep self” and a “rapid flow of truly spoken desires or feelings”; exclamation, “a seeing, Sensing, spoken loudly by the suddenness and meaning of it”; and the rose flush, he relates, “comes as a flower is supposed to. A flush comes to me as a hand is dealt in cards. A flush. An opening out to the softness of beauty or a loveliness of inspiration.”

McClure, always in search of the true biological self — as opposed to culturally imposed views of self — hailed a breakthrough in his work when he wrote “Rant Block” (The New Book/A Book of Torture, 1961). That poem, he says, “went through the crust of the verbal universe for a sea lion swim in the world of physiology.”

The Rose Flush

As the 1960s unfolded, McClure’s emphasis gradually shifted from poetry to drama. Haselwood recalls that one of McClure’s first plays was performed at the Bat Man Gallery, located just downstairs from where McClure, his wife and young daughter lived.

“There was a whole scene around that art gallery,” Haselwood says. “Bruce (Conner), who didn’t live too far away, Mike and I were all involved in activities there.”

McClure’s most famous and controversial play, The Beard (1965), garnered a request from Jim Morrison for the two to meet. It also garnered obscenity trials that occupied the playwright for years. McClure later extended thanks to the play’s actors and other principals “for all we have gone through together to make a blue velvet eternity.”

To McClure, who senses profound unity in our multifarious universe, as in the ancient Taoist view of the cosmos as an uncarved block, “velvet eternity” means “the eternity that we touch with our fingertips, that we smell with our nose, that we feel with the seats of our buttocks when we sit on a chair, when we hear the sounds of someone else who’s speaking. Those are the parts of the universe that are available to our prehension, those are the parts of the universe that we light up around us when we are the universe prehending itself.”

McClure, who continues his explorations in prose and poetry, once described a Robert Creeley poem as uniting “awareness of living environment, oneness of time, deepening of consciousness and myriad-mindedness.” That is an apt description of his own uniquely unifying body of work.

McClure’s poetic voice — like a hawk’s echoing KEEEEERRR-eer — keens and celebrates, in unison.

THE GROUP

The Wichita Group is a trio of artists — Michael McClure, Bruce Conner, David Haselwood. In the early 1950s they studied (and played) at the University of Wichita. After leaving Kansas, each of them, independently, found home in San Francisco. There, they made art history, McClure as a poet and playwright, Conner a filmmaker and visual artist, Haselwood a publisher. This article is the first in a three-part series about these three artists. For further background on their days at WU, see “Against the Grain” in the summer 2000 issue of The Shocker.