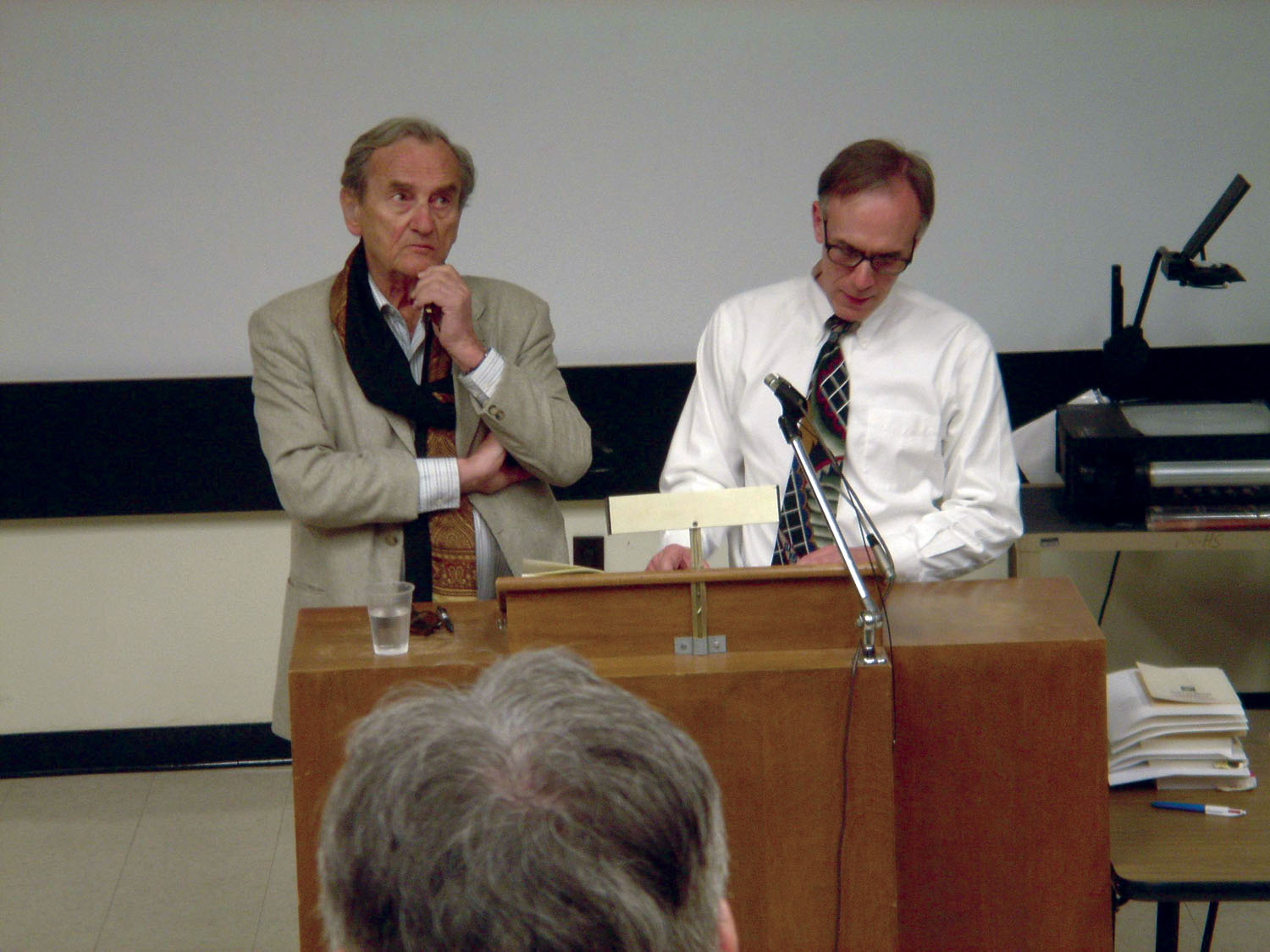

Deguy (left) at a bilingual reading on campus April 24. Baldridge

has translated Deguy’s collection Gisants (Recumbents, Wesleyan

UP 2005).

The French word gisant refers first to a style of funerary statuary that shows the deceased — usually nobility — reclining on his own tombstone. Metaphorically, this extends to the dead themselves or, from the original memorial purpose of the statue, any symbol of a lost or invisible presence. The poet Michel Deguy’s 1985 collection Gisants, translated as Recumbents by WSU associate professor of modern and classical languages and literature Wilson Baldridge, encompasses these senses and more of this complex and sometimes enigmatic word.

Baldridge first encountered Deguy and his work as a graduate student at SUNY-Buffalo in the 1970s. He’s been a fan ever since. Deguy was trained in Continental philosophy (Descartes, Kant, Heidegger) and is, Baldridge says, a “major player” in the European intellectual avant-garde. His poetry has won numerous prestigious awards, but Deguy also writes philosophical essays and criticism, teaches literature at the University of Paris at Saint-Denis, serves on the editorial board of several publishing houses and is founding editor of the journal Po&Sie. Not to mention his friendship with the deconstructionist philosopher Jacques Derrida (1930-2004) — in other words, reading Deguy is no mean feat, much less translating him.

The greatest challenge Baldridge faced was “not translating the words but the ideas. Words have specific connotations. If you translate word for word, you get a string of words — not the thought.” Especially in Deguy’s work, which jumps from vernacular to formal, didactic terminology and commonly switches from lyric to prose, what Baldridge calls “the nexus of rhythm, figure (i.e., of speech) and image” requires elbow grease and a willingness to constantly revise. In effect, a translator must write a new poem, attempting to recreate the emotional effect on the reader as well as the author’s intended subject and tone.

Baldridge, though, found translation only the beginning of the 10-year project that produced Recumbents. Finding funding and a publisher for a work with an admittedly limited audience also proved difficult. But a subvention provided by WSU vice presidents Robert Kindrick (who passed away in May 2004) and Gerald Loper helped buy the reprint rights to Gisants from Gallimard, its original publisher. Wesleyan University Press released Baldridge’s volume (with an afterword by Derrida) earlier this year; to celebrate, Baldridge invited Deguy to WSU in April for a bilingual reading.

And the poetry? For all its difficulty, Recumbents cannot be called dry. Deguy’s works are concerned with music and image; he coins the playful mouthful of a word “equalifraterniliberty” and describes the moon as “powdered like a Japanese woman.” But each poem is also a statement of poetics. The concept of gisants underlies this tension between rhetoric and beauty: “Art,” says Baldridge, “is about trying to recuperate some sort of presence, incorporate or embody something that isn’t immediately present.” Likewise, Recumbents conveys abstract concepts in concrete, “real” words.