WSU College of Fine Arts Dean Rodney Miller sees the broad sweep of artistic enterprise behind art and design’s venerable MFA program. “Prior to my coming to WSU,” says Miller, a professional singer and educator who arrived in 2004 from the University of Nebraska-Kearney, “I admired Wichita State and its reputation, especially in the fine arts. I knew about the School of Music and a number of its programs and faculty members, with whom I had worked professionally. I also knew to some extent about the programs in performing arts and in art and design. What I did not yet appreciate was the quality and depth of work being done here. The fact that we are celebrating the 50th anniversary of the MFA program in art and design means that we are among the first in the United States to have offered such a program. This anniversary is an opportunity for us to say, ‘Look at what we’ve done. Look at what we’re doing.’”

Don Byrum, a printmaking professor who’s served as chair of the School of Art and Design since 1993, reports that the school is “pushing toward 500 majors,” with students enrolled in a full spectrum of courses in graphic design, studio arts, art history and art education. On the graduate level, the school offers programs leading to MA and MFA degrees, the latter of which prepares students for careers as professional artists, as either an independently supported artist or an artist teacher on the college or university level. MFA students at Wichita State declare majors from four disciplines: ceramics, painting/drawing, printmaking, sculpture. “Our faculty members are extremely dedicated,” reports Byrum, who is on sabbatical. “They’re dedicated to their art, and they’re dedicated to teaching and students.” While the MFA program offers students far-ranging benefits, Byrum thinks the most essential may be “the opportunity to develop their own artistic style.” He explains, “At many other universities, students may work with perhaps two faculty members per semester. Here, the entire faculty works with students. That’s eight people per student, which encourages different approaches to self-expression.”

Mira Merriman, professor emeritus of art and design, who moved to Wichita in 1965 when hired to establish an art history department, echoes Byrum’s thought: “I fell in love with the art school. This place has turned out real artists, people who found, not imitations, but their true voices.”

Ron Christ, professor of painting and drawing who has taught at Wichita State since 1976 and who, in his own award-winning artistic pursuits, has journeyed from strongly geometric still-life imagery, to landscape and into figurative forms, says he’s “consistently impressed and very proud of our MFA graduates.” He adds, “We help and encourage the MFA student to develop artistically, intellectually and professionally. The ongoing accomplishments of MFA students and alumni are the clearest and most rewarding evidence that we are achieving our mission.”

Even the most cursory survey proves Christ’s point. From private studios and public galleries and museums, to college and university classrooms throughout Kansas, across the country and around the globe, MFA graduates are voicing notable additions to the grand conversation that is the visual arts. And they’ve been doing so for half a century — and counting.

The year Norm Cash ’54/55 (d. 2000) and Oscar Larmer ’55, both painters, became the University of Wichita’s first MFA graduates, the conversation often turned to abstract expressionism. With its emphasis on individuality and spontaneity, abstract expressionism moved in contrast to the more conventional themes of social realism and regional life that dominated much local art. It was WU faculty and students, in large measure, who introduced and gradually won over the wider community to appreciation of newer subjects and styles of art.

“The MFA program had a tremendous impact on Wichita,” says Jim Johnson ’75, an art historian and consultant to the curator of Emprise Bank’s noted art collection, which contains scores of works by WSU faculty and WSU-educated artists. “It brought young, talented students who were interested in new, more avant-garde art. They opened galleries, created their own exhibitions and generally challenged the existing conservative art community that existed in Wichita.”

From his home in Marshall, Mo., Vernon Nester ’55/58 recalls, “The drips and dribbles of the abstract expressionists, especially Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, were very influential when I was in college. I could splash along with the best of them — although later I went back to more representational work.”

Larmer, a retired Kansas State University art professor (1956-89) and co-author of 1982’s A Foundation for Expressive Drawing, relates that as an MFA student he studied with painters Eugene McFarland (d. 1956) and Robert Kiskadden (d. 2004). Before his death in a car accident, McFarland was head of WU’s art department and director of the Wichita Art Museum, which was then operated under the municipal university’s authority. “I was a graduate teaching assistant,” Larmer says, “and I worked as an assistant director of the art museum. I remember it was open in the afternoons from one to five, Tuesday through Sunday.”

Nester, too, worked at the art museum. Now retired from Missouri Valley College, where, he says, “life was congenial — and I never had a class before 9 a.m.,” he relates it was at WU that he developed his “great appreciation for academic life. The other art students — including Alan Munro (’56) and Phil Dodgen (’56) — and the faculty, they made me realize this is the kind of life I want.” On the faculty side, Kiskadden, in particular, held special significance for the young artist. Nester explains, “He was my adviser, and I owe him a great deal. Even years after college, as a mature man, when I went to see him, it was always ‘Mr. Kiskadden.’ Never anything else.”

Larmer and Nester also remember with respect a number of other WU art faculty, among them art history professor John Simoni, potter John Strange, silverworker Mary Tingley and David Bernard, who had arrived on WU’s campus in 1949 to organize and develop the school’s printmaking department — the first in Kansas.

“The art department was housed in the old library (built in 1909),” reports Bernard, professor emeritus of studio arts who lives in St. Cloud, Fla. “The building was brick and limestone, a neoclassic type of building with columns. It had wooden floors and a little gallery area. My printmaking classroom was on the second floor. There were skylights. It was beautiful — but it could get hot.” He adds that ceramics were attended to in the basement of the library-turned-art-building, where Strange had built a kiln.

In 1958, Bernard and Kiskadden were among Wichita artists who came together as the indeX group. A copy of an invitation to the group’s opening exhibition of paintings, prints and sculpture places the event in the “Little Gallery, University of Wichita Art Building.” The group, which also included Paul Edwards ’59 (d. 2005) and Rex Hall ’58 (d. 2004), opened the indeX Gallery at 116 1/2 S. Broadway. A Dec. 31, 1958, Wichita newspaper article records, “An Air Force officer from New York dropped in to see the abstract paintings. ‘I am surprised,’ he said. ‘People in New York told me there was no art in Kansas. I think New York had better find out what is happening in Kansas.’”

As the ’50s merged into the ’60s, the walls of WU’s beautiful (but periodically hot) art building rang with the work and the conversations of an ever-growing number of MFA student artists. Some of them were taking note of minimalism, an impulse to strip art down to its purest form, while others keyed on the emergence of Pop Art. Still others focused on the reappearance of the figure as a meaningful subject in abstract expressionism.

Among that set was James G. Davis ’59/63 (see The Shocker’s “Peripheral Visionary,” fall 1999). According to Novelene Ross ’69, a former Wichita Art Museum chief curator, Davis “in his own singular way, shaped that movement.” Fred Burton ’68/75, professor of drawing and painting at the Memphis College of Art, says, “My first bohemian art hero was James Davis. His expressionistic figure paintings are incredibly impressive.”

WSU art students use classroom and laboratory facilities in the McKnight Art Center and nearby Henrion Hall. The McKnight Art Center provides extensive space for exhibition of student work. The Clayton Staples Art Gallery offers guest artist and thematic exhibits in addition to student BFA and MFA graduation shows. Also housed in the center is the Ulrich Museum of Art.

A prolific artist, Davis taught for 21 years at the University of Arizona, retiring in 1993. He now splits his time between home bases in Arizona and Novia Scotia. A talented printmaker, he is known primarily for his paintings, which are not only in private collections but also in the permanent collections of, among others, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Museum of American Painting and Berlin’s Berlinische Museum. His works entangle viewers in a darkly fascinating, richly narrative world alive with the tension and strangeness of ordinary reality — as filtered through his extraordinary mind.

Davis’ artistic endeavors while at WU included opening a downtown gallery, Bottega, with five of his friends, including Eugene “Skip” Harwick ’62/65. In 1999, Davis reported, “We were a pretty poverty-stricken bunch. We tied our pants up with rope. We ate once a day. And when we had an opening, we took turns being the waiter who mainly served the rest of us.”

In 1963, WU entered the state’s university system, thus becoming Wichita State. Bernard, Kiskadden and other art faculty continued making art while encouraging students to expand their own artistic vocabularies. Sadly, many student and faculty artworks of this period were destroyed in 1964, when fire swept through the second floor of the art building. The building was later razed, except for a stand of columns that grace the campus entrance on 17th St. near Hillside.

Burton, who began undergrad studies at WSU after the fire, remembers a pre-fire visit to the campus: “The art building was a three-story mansion, and the smell of linseed oil and turpentine in the painting studios and the beams of brilliant light streaming into the rooms drew me in.”

The fire, Bernard reports, certainly changed things. He says, “The building burned over spring vacation. We moved the salvageable remnants and worked for a time under makeshift and primitive conditions.”

Primitive conditions notwithstanding, art-making at WSU flourished. To offer only two examples, Donald Roller Wilson ’64/66 produced prints and began developing a most amazing style of painting that ripened into playful, luscious compositions stylistically reminiscent of Hieronymous Bosch but conceptually all his own. “My art, briefly, is indescribable,” he says from his studio in Fayetteville, Ark. Technically influenced by the French neoclassicists, especially his favorite, Ingres, Wilson’s work also harks back to Flemish and Dutch floral masters, something easily seen in the artwork featuring “Cookie” that serves as the cover of this issue of The Shocker. “My work has a lot to do with things not in my work visually,” he says. Famed for the intricate storylines that invisibly layer his creations, Wilson loves to play with patterns and scale — on as many communicative planes as possible.

And Richard Ash III ’66/68, who lives in Wichita Falls, Texas, and teaches at Midwestern State University, deepened his knowledge of drawing, painting and various print processes — and forged key relationships. “The single most important relationship for me was with the then-new painting instructor, John Fincher,” Ash relates. “Without a doubt the networking among artists was the most valuable tool I left graduate school with.”

In addition to Fincher, other incoming art faculty of this period included art historian Merriman, sculptor Don Schule (who created, recalls Jim Hellman ’72/75, “these polyurethane cloud forms that could actually rain. Grass grew under them.”) and potter Richard St. John.

Kent Follette ’75, a successful potter based in Ruston, La., says, “The thing I learned from WSU professors — especially Rick St. John — was the importance of craftsmanship. His demand for quality and craftsmanship was, to me, the essence of the whole program.” Although Follette says he first heard about Wichita State’s reputation in ceramics while an undergrad at Louisiana Tech, WSU “was too far up the bayou for me.” While at Tulane, however, he decided to check things out. Arriving on campus, he met St. John at work mixing clay. The WSU potter talked with Follette and bought him a sandwich. “That’s what it took,” Follette says with a laugh. He adds, “I was back in Wichita about two years ago, and I looked around the campus. I saw pot after pot — some really good, strong student pots. I just looked around, didn’t talk to anyone, but I felt an incredible amount of energy, saw an incredible amount of work being done — saw piles and piles of clay.”

In 1974, WSU’s art community celebrated the completion of the $2.6 million McKnight Art Center within which was also unveiled the Ulrich Museum of Art. Kiskadden, who had become an assistant dean in 1971, served as chair of the building committee. On hand for the complex’s Dec. 7 dedication were several hundred guests, Edwin A. Ulrich, the museum’s benefactor from Hyde Park, N.Y., and Martin Bush, WSU vice president for academic resource development and the man responsible for Ulrich’s gift, as well as some 2,000 works of art held in university collections. Retired and living in NYC, Bush was also the one to persuade the Student Government Association and a group of Wichita art patrons to fund a mural by Joan Miró (d. 1983). Commissioned in 1972 and installed in 1978 on the museum’s south wall, Personnages Oisseaux (Bird Characters) is a Venetian glass and marble mosaic and one of Miró’s largest works. The artist once said he wanted this mural to “become part of the consciousness of those young people, the men and women of tomorrow.”

Sculptor Tom Gormally ’79 of Seattle names WSU faculty members Schule, printmaker John Boyd and art educator and critic Robert Morgan as among those who broadened his artistic consciousness as an mfa student. “Although I was a sculpture major, the freedom to explore and express myself in any medium that the school provided was vital to my development as an artist,” he says. In his work, Gormally typically employs multiple mediums and often uses the socio-political realities of a particular place to drape his sculptures with layers of meaning. For instance, Watching the River Flow is an 18-ft tall chair that leans lazily against the brick wall of a river-front building. The comfortable, contemplative attitude of the deftly rendered chair stands in stark contrast to its setting: along the Lagan River in Belfast, Northern Ireland.

Plans are being made for an MFA Alumni Reunion in April 2006 to coincide with the dedication of McKnight 210 as the Mira Pajes Merriman Lecture Hall, featured exhibitions at the Ulrich Museum and Wichita Final Fridays and WSU Shift Space gallery openings.

Gormally says the MFA students developed a strong sense of community. “It was an exciting time at WSU,” he recalls. “We carried that excitement into the community. Jane Eby (’79/05), Randy Kust (’79), John Clampett and I started the Ballpark Studios and Gallery on Douglas. We had exhibitions, critique nights, parties and performance art presentations. And we provided space for people to do experimental work and curate exhibits.”

By 1980, 80 MFA graduates had passed through Wichita State’s program and were artfully contributing to the wider world with their art and often their teaching. Even a truncated list of such WSU-educated artist educators is long and far-ranging: Richard Slimon ’57, Emporia State; Corban LePell ’59, Cal State-Hayward; Cecil Howard ’63, Western New Mexico University; Edmond Gettinger ’66, Western Illinois University; Sally (Mitchell) Segal ’67, University of Texas; Judith (Burns) McCrea ’70, University of Kansas; Lowell Baker ’71, University of Alabama; Don Osborn ’71, SUNY-Plattsburgh; Stephen Missal ’72, Art Institute of Phoenix; James Rogers ’72, Glenville State College in West Virginia; Nancy Means ’77, Colorado Institute of Art; and, at Kansas’ Fort Hays State, Michael Jilg ’72, Leland Powers ’73 and Kathleen Kuchar ’74.

As the ’80s got properly under way, WSU’s classrooms and studios filled with new students and fresh discussions and productions of art. Bernard, in 1983, and Kiskadden, in 1984, retired from teaching, although their influences ripple on. “I feel happy I was able to teach there for so long,” Bernard says. “It was rewarding helping and seeing students grow — some of them grew very fast.”

While studying ceramics at the University of Iowa, George Lowe ’81 heard about Wichita State’s tradition of pottery making. He was impressed by the long-running program developed by St. John. Lowe, who lives and works in Decorah, Iowa, reports he learned much from WSU art faculty. “Most important,” he says, “they helped me understand what my work was about. They helped me learn and articulate the vocabulary of pottery.” He adds, “Rick St. John was always saying to us, ‘Make sure you know where you’ve been, where you are and where you’re going.’” Another nugget of St. John advice is reported by Caroline Kahler ’99, art professor at Bethany College in Lindsborg, Kan.: “‘The answers come when you work.’ This quote from Rick St. John is now in my studio. One can think about art, talk about art, but until you get in the middle of making your art, you can’t possibly resolve the issues of process and content.”

Now retired from teaching, but actively pursuing his art in Cortez, Colo., St. John says he’s proud of his former MFA students and the inspiring work they are producing. Today, Ted Adler, assistant professor of art, and visiting artist Stephanie Lanter, along with their ceramics majors, continue WSU’s ceramics tradition.

Painter Marlana Stoddard Hayes ’83 of West Linn, Ore., says perhaps the most valuable thing she took away from her WSU education was “perseverance. You never know what your circumstances are going to be, so you have to learn how to make things happen for yourself.” She names Boyd and Christ as particular influences, saying, “A student picks up on the day-to-day attitudes and work ethics they see.” In today’s WSU painting and drawing classrooms and studios, Christ is joined by faculty and adjunct faculty James Caldwell ’02, John Oehm ’81, Victor Rose ’79/97, Nate Theisen ’01, Carol Ranney, Paul Flippen, Robert Bubp and, in decorative painting, Diane Thomas Lincoln ’77.

Sculptor Michael Flechtner ’84 of Van Nuys, Calif., serves on the board of trustees for the Museum of Neon Art in Los Angeles and has permanent works installed in such far-flung locations as LA, Tokyo, Ohio and Alaska. He says that while at WSU, he “discovered my roots as an artist. That is, after learning theory, technique, history, materials and so on, I realized my art-making process stemmed from childhood, going through my grandmother’s junk drawer, finding string, pulleys, batteries, screws and wires and trying to put them together in some kind of machine or structure.” The art history he gleaned from Merriman and Stockton Garver, he says, “gave me a context for my art.” And he adds with a laugh, “That danged WuShock always comes to mind. I keep thinking what he’d look like animated in neon!”

Flechtner decided on WSU primarily because Jay Sullivan, now professor of sculpture with SMU’s Meadows School of the Arts, took a personal interest in his work: “I liked that approach and figured if I had the tools to work with, I could get the work done.” Sculpture, housed in Henrion Hall, is today taught by Barry Badgett, associate professor, and Daniel Jensen ’98/01.

Printmaker Andrew Totman ’86 has lived in Sydney, Australia, for the past 10 years, teaching at the National Art School and Knox Grammar School. Through a University of San Diego professor, Totman learned of Boyd and his work at WSU. When asked what comes to mind when thinking of Wichita State, Totman’s responses are “Boyd, Miró’s mosaic and the outdoor sculptures.” He adds, “The first year out of WSU, I was an assistant curator at the Ulrich, giving many tours about the outdoor sculptures. I still use these images in lectures I give today.”

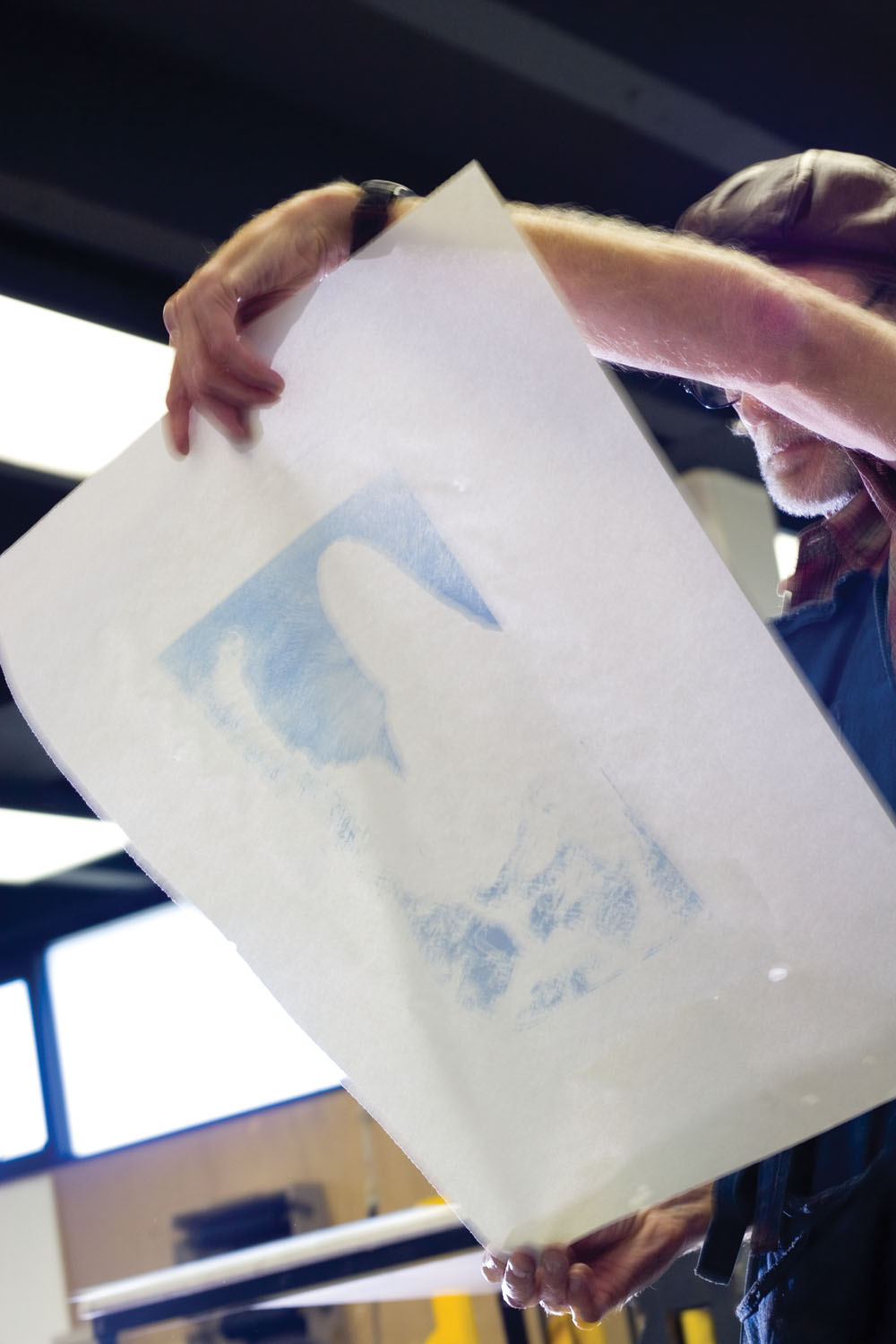

Boyd continues as head of printmaking at WSU. He reports he’s especially “happy with the placement of the print graduates in the last several years. Since 2000, all five of the grads have been placed in full-time college teaching jobs. That is significant, as job success is not usually that good.”

While the landscape of art at WSU has certainly changed over the course of half a century, some things recur so often they seem permanent. One is the impulse first seen in the indeX artists to take their art into the wider community. A recent incarnation of this was the formation of the Famous Dead Artists in 1993 (“Group Dynamics,” The Shocker, summer 2003). From this nine-member group, Marc Bosworth ’92 and Leigh Leighton-Wallace ’80/96 hold MFA degrees. And the artistic pursuits of the collective of artists called the Fisch Haus as well as the new WSU Shift Space, which showcases the work of faculty, students and alumni, are tied wholly or in part to WSU. Boyd comments, “The ‘Wichita underground’ scene is very good with many art groups represented. The Old Town art scene is one of the active areas in our city. WSU is the leader of the art scene in the Wichita area.”

Hellman views Wichita State’s MFA program from multiple perspectives. A WSU graduate of painting (BA) and of graphic design (MA) and now the acting chair of art and design, he sums things up this way: “We have amazing MFA students and faculty here. Our faculty provide the students a solid grounding in tradition. At the same time, they push them to go beyond.”