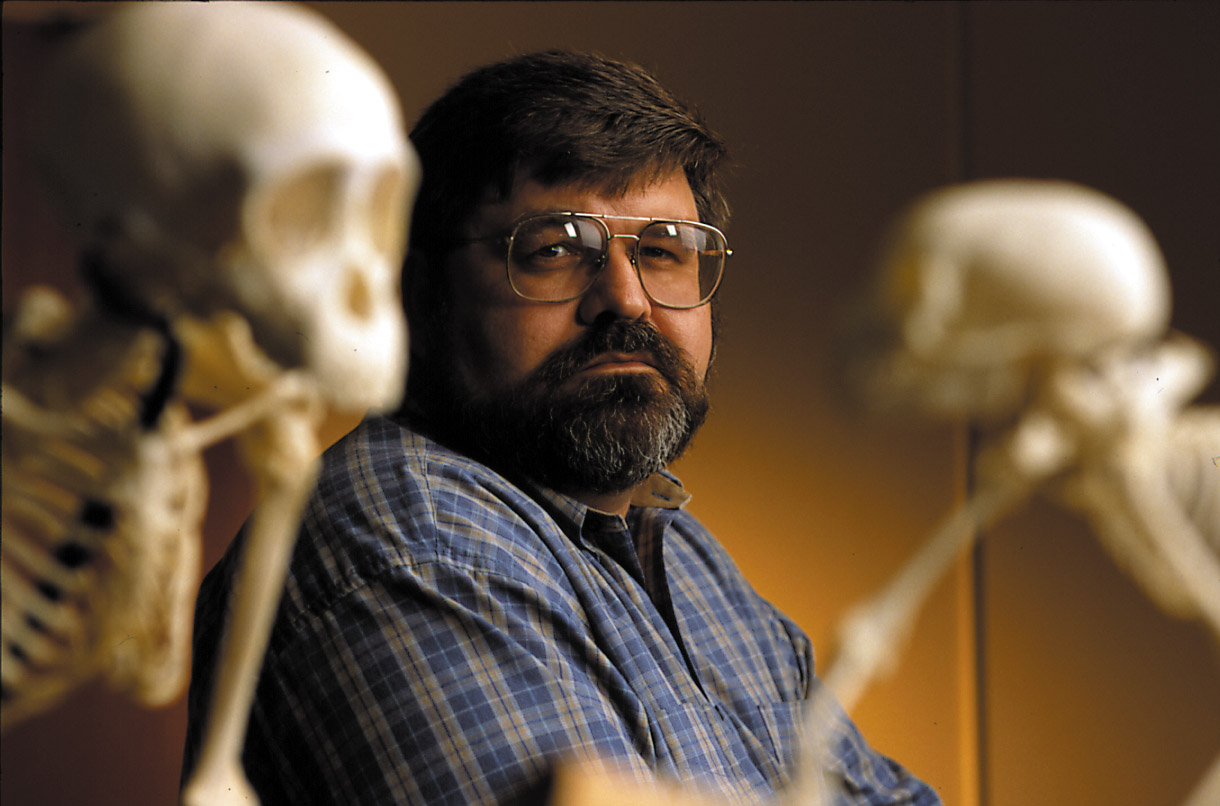

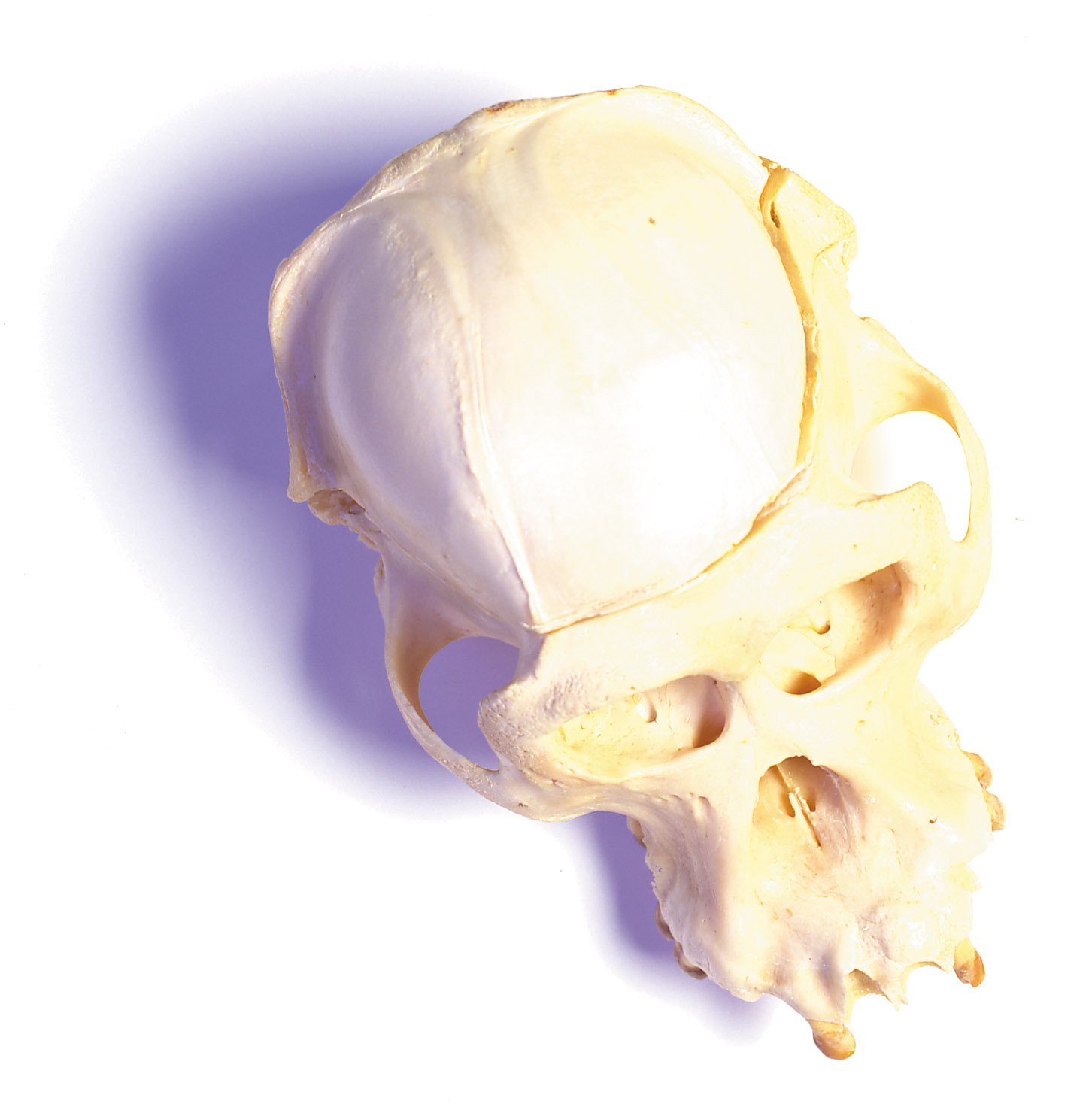

Peer Moore-Jansen, Wichita State's only physical anthropologist, can coax narratives from even the most reluctant of bones. From a second-floor lab room in Neff Hall, he reaches for the whitish gray skull of an orangutan, explaining as he runs his finger across a small indentation on the inside of the skull, "She had epileptic-like seizures when she was alive."

He hands the cranium across the lab table, pointing to the tiny pockmark that pressure from a deadly brain tumor had left behind. The feel of the bone is dense and smooth and surprisingly cool.

Moore-Jansen specializes in skeletal biology and is an expert in the analysis of historic and recent forensic skeletal materials for both human and non-human primate skeletal anatomy. A listing of his professional interests includes human variation, forensic anthropology, comparative osteology, bioarchaeology, dental pathology and microwear, and evolutionary biology.

A member of WSU's faculty for a decade now, this scholar and award-winning teacher lends his expertise to law enforcement agencies throughout Kansas, helping investigators identify homicide, suicide and burn victims.

Over the years, Moore-Jansen has assisted in nearly 100 forensic cases. One of his earliest involved reconstructing what had happened during a Woodson County house fire that claimed at least one life. Charged with positively identifying the victim and labeling the death as either natural or homicide, Moore-Jansen and the other investigators not only studied the recovered body but excavated thousands of tiny, charred bone fragments from the site.

The evidence led them to conclude that the victim had been done in by accident: he had fallen asleep smoking. But he hadn't died alone. Those tiny, charred fragments of bone bore witness to the existence of a litter of puppies, protected to the end by their mother.

In 1991, Sedgwick County authorities called for Moore-Jansen's help when the remains of a child were discovered in a plowed field near Wichita. After carefully sifting through 12 bags of skeletal material, Moore Jansen and a forensic dentist determined the body was that of 9-year-old Nancy Shoemaker, who had been murdered after being abducted on her way to a neighborhood store to pick up a bottle of Pepto-Bismol for her little brother.

"I still feel for the Shoemakers," Moore-Jansen says, adding that during the course of the case's ensuing trials it must have been torture for the grieving parents to hear him talk about their daughter's bones.

Because of dental records, the bones were not difficult to identify, Moore-Jansen relates. What became intriguing about the case from a forensic scientist's point of view was narrowing down the time the body had been buried. The timing of this gruesome activity was a key piece in the prosecutor's arguments.

Moore-Jansen and other investigators spotted a mark abraded into one of the child's bones, a mark determined to have been made by a farmer's disc. After learning when the farmer had worked his field, they had their timeline. That, along with other damning evidence, led to the conviction of two men. The accomplice is now serving an 8-to-16-year sentence in a Kansas prison, while the prinicipal sits on death row in Texas for the murder of another girl.

As grisly as Moore-Jansen's forensic work may seem, it is an essential enterprise that challenges the mind to recognize meaningful pattern in seemingly haphazard occurrences. To explain, Moore-Jansen cites this example: because heat turns bone different colors, depending on the flame's intensity and duration, a biological anthropologist can learn to read the changes in color imprinted on bones during the course of a fire. "You can see where the hottest areas were," he says. "You can see what areas (of the body) burned first."

As a practicing anthropologist with ongoing work outside the classroom, Moore-Jansen is able to provide advanced forensic anthropology students the irreplaceable opportunity of learning through involvement with real case studies and hands-on field work. As a scholar with scores of published works to his credit, he also coaches students on the importance of writing papers for a professional audience. As the teacher he is at heart, he's quick to brag on the successes of his students, whether they're tackling problems in the field or presenting papers at a regional conference. "I'm proud as can be," he says, "when students of mine do well." And as a scientist who works daily within the framework of evolutionary thought, Moore-Jansen has had an interesting time in Kansas this summer.

Difficulties on Theory

The day the Kansas Board of Education voted 6 to 4 to de-emphasize evolution in the state's science curriculum for public school children, kwch-tv 12, Wichita's cbs affiliate, showed up in Moore-Jansen's campus office to record his take on the news. He didn't like it. Yet, while a number of other Kansas scientists and educators responded with disgust and anger to the boe's action and a storm of national and international media attention swirled around the story, this Danish-born anthropologist seemed somewhat bemused, even a touch sad, about the whole brouhaha.

The day the Kansas Board of Education voted 6 to 4 to de-emphasize evolution in the state's science curriculum for public school children, kwch-tv 12, Wichita's cbs affiliate, showed up in Moore-Jansen's campus office to record his take on the news. He didn't like it. Yet, while a number of other Kansas scientists and educators responded with disgust and anger to the boe's action and a storm of national and international media attention swirled around the story, this Danish-born anthropologist seemed somewhat bemused, even a touch sad, about the whole brouhaha.

That's because Moore-Jansen sees the boe's Aug. 11 decision as "taking away an opportunity to learn." While the new curriculum standards don't ban the teaching of evolution, the subject will no longer be included in statewide assessment tests for students, which leaves the decision of whether to teach the concept or not up to the state's 304 local school boards. Specifically, the newly adopted Kansas Science Education Standards stresses four "unifying concepts and processes": systems, order and organization; evidence, models and explanation; constancy, change and measurement; and form and function. Had another version of the standards been approved, a fifth concept would have been included, patterns of cumulative change. The passage would have read:

Patterns of Cumulative Change: Accumulated changes through time, some gradual and some sporadic, account for the present form and function of objects, organisms and natural systems. The general idea is that the present arises from materials and forms of the past. An example of cumulative change is the biological theory of evolution, which explains the process of descent with modification of organisms from common ancestors. Additional examples are continental drift, which is part of plate tectonic theory, fossilization and erosion. Patterns of cumulative change also help to describe the current structure of the universe.

The deletion denies the theory of evolution status as one of modern science's "unifying concepts and processes." Supporters of the new standards, including WSU psychology professor Paul Ackerman, say that Kansas school children will be encouraged to think critically by being allowed the freedom to explore interpretations of scientific data other than evolutionist ones. Critics, on the other hand, believe the omission will lead to students being unprepared for college-level science courses "because evolution is the fabric that binds all sciences together," as WSU biology professor Steve Doggett put it during a campus debate on the boe's decision in early September.

Doggett, Moore-Jansen and others critical of the new standards decry the downplaying of the scientific efforts of many scientists and thinkers whose names and works are important in the history of evolutionary thought, including, of course, Darwin and his The Origin of Species, which was sold out on its first day of publication in 1859 and is consistently held to be the major book of the last century. Called the most important figure in the field of biology, more important in his impact on history than Copernicus, Newton or Einstein, Charles Darwin is hailed as one of the great field naturalists of all time.

"When it comes to the boe's decision," says Cathy Moore-Jansen, an associate professor and acting coordinator of collections development at WSU's Ablah Library, "sadness, more than anything else, comes to Peer. He's afraid the students won't learn the things they should."

Variation under Nature

Cathy Lyle met her future husband in the summer of 1973. While she was studying anthropology at Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas, Peer was studying archaeology at the University of Copenhagen and spending his summers doing field work in Denmark, Holland, Germany and Sweden. It was the field work that brought them together. When an international group of students assembled to help excavate a Mesolithic site in the Netherlands, the two undergrads found themselves at the same railroad station. Cathy remembers seeing Peer for the first time. "He was cute," she says with a laugh. "The Americans and the Danes got along really well. I think there were about three marriages that came out of that dig."

Cathy Lyle met her future husband in the summer of 1973. While she was studying anthropology at Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas, Peer was studying archaeology at the University of Copenhagen and spending his summers doing field work in Denmark, Holland, Germany and Sweden. It was the field work that brought them together. When an international group of students assembled to help excavate a Mesolithic site in the Netherlands, the two undergrads found themselves at the same railroad station. Cathy remembers seeing Peer for the first time. "He was cute," she says with a laugh. "The Americans and the Danes got along really well. I think there were about three marriages that came out of that dig."

After another summer dig the following year, Peer and Cathy decided to end, as she calls it, the "back-and-forth" part of their relationship. Peer came, with a single suitcase of belongings, to the United States to stay, and the couple married on Aug. 23, 1975 in Texas. They finished their degrees at Texas Tech. The change of environment was striking, and Peer still misses Denmark's seascapes. "This summer, we went back to visit my mother," he relates. "I sat and stared at the ocean." Yet the most difficult aspect of coming to the U.S. for Peer, who has epilepsy, was adapting to more limited public transportation. "The lack of mobility was a real restriction for me here," he says. "In Copenhagen there are buses and trains; mobility isn't a problem."

From Texas Tech, Moore-Jansen went on to the University of Arkansas-Fayetteville, where, with a nudge from one of his professors, his professional interest shifted from archaeology to biological anthropology. J.C. "Jerry" Rose, a physical anthropologist, assigned the graduate student to examine the teeth of prehistoric people as indicators of their diet. "He became excited about dental anthropology," Rose recalls. "I'm very pleased and proud of his good work through the years. Peer's enthusiasm and persistence in the lab, his ability to do hard work, that's what's necessary in our field. Peer keeps attacking a problem until it gets solved."

With master's degree in hand, Moore-Jansen continued his studies in biological anthropology at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, where he completed his doctorate in 1989. It was at Tennessee he fine-tuned his teaching technique and philosophy with the guidance of two anthropology professors, William M. Bass, now retired, and Richard L. Jantz. Moore-Jansen credits them, among others, with teaching him the importance of keeping promises, giving students loads of opportunities and rewarding them for their hard work.

Jantz credits his former grad student with being instrumental in the development of the comprehensive National Skeletal Data Bank. "When he got here," Jantz explains, "we were just initiating a project to recover information from forensic cases on a national scale. Only physical anthropologists are (legally) able to examine the skeletal remains of modern Americans, and we wanted to set up a database for information we could use for identification criteria. Peer immediately saw how we could utilize the personal computer, which was just then coming into broader use, in the management of the project. I'm telling you, he's the hardest worker I've ever seen."

When Moore-Jansen arrived on WSU's campus in 1989, he brought with him a broad array of laboratory and field-work experiences and a well established reputation as a researcher in human skeletal evolution. At Wichita State, he's not only earned further recognition for his scholarly pursuits but has also proven himself to be a master teacher.

In 1998, he was honored with WSU's Leadership in the Advancement of Teaching award, and this year he took home an Excellence in Teaching award. Like his mentors, he believes that in order to successfully engage students, a teacher must cultivate professional relationships with them — from something as simple as learning a student's name to spending as much time as necessary for a student to grasp a concept. "Teaching involves being aware of an individual's needs," Moore-Jansen says.

"Peer wants to make the connection with his students," Cathy Moore-Jansen says. "He's very open-minded about others' views. I think that's important when you're dealing with controversial or sensitive subject matter, like he does. He's so dedicated and cares so much about the students, that means a lot of late nights — sometimes too many for my liking."

Each semester, WSU anthropology professor Don Blakeslee asks the students in one of his classes to share what the best and the worst classes are that they've taken at Wichita State, and why. "Literally half of the students in the class," Blakeslee reports, "gave Peer Moore-Jansen's name as the best."

Why is his name mentioned so often? "His intense interest in his area of study — he absolutely loves what he does," Cathy Moore-Jansen says. "That enthusiasm communicates to the students. Plus, he knows so much about what he teaches."

One of his former student lab assistants, Angela Benefiel, explains his effectiveness in the classroom this way: "He's highly student-oriented. He works with students and brings out the best in them."

More than Old Bones

Founded in 1967, Wichita State's department of anthropology was going strong when Moore-Jansen joined the faculty 10 years ago. But his coming has certainly enriched the department's offerings and broadened its scope.

"Peer has built up our biological anthropology program from a very small student count of one or two graduate students to a thriving part of our mission," Blakeslee reports. Today, the program boasts 15 core students.

Moore-Jansen has also worked hard to add to the department's comparative collections. "When I got here," he notes, "we had a few prehistoric bones, but that was about it. " Today's anthropology students have access to a true forensic laboratory — with hundreds of examples of bones to study.

Complementing the department's forensic lab are these other special facilities: the Lowell D. Holmes Museum of Anthropology; comparative collections and research laboratories in archaeological, biological and sociocultural anthropology, a scanning electron microscope facility; geoarchaeological facilities for X-ray diffraction, X-ray fluorescence, and DTA and petrographic analysis; a primate research facility; and summer field schools in archaeological and sociocultural anthropology. The department offers three master's programs, designed for students who want to pursue a doctorate in anthropology, teach college or work in a museum or medical examiners office and for students who have a specific interdisciplinary interest in anthropology in combination with, for instance, health professions or education.

Including associate professor and current department chair Moore-Jansen, WSU's anthropology department comprises eight faculty members. There were only three in 1967. Each is a practicing anthropologist with impressive records of publication: Dorothy K. Billings, Blakeslee, John Carpenter, David T. Hughes, Robert Lawless, Moore-Jansen, Clayton A. Robarchek and James H. Thomas.

This summer the whole crew moved from McKinley Hall into renovated Neff Hall. For the first time since the department's founding, all anthropology department units are located in a single building.

For the move, Moore-Jansen carefully packed and unpacked the fragile bones, some chalk-white, others bearing tones of yellow, red, gray and brown, but each so vital in the teaching of future anthropologists.

"Bones," he says, "fascinate me."

The WSU Anthropology Campaign is underway. This fund-raising effort has targeted services and equipment that will enhance teaching and research and expanded museum space as top priorities. For information on giving opportunities, please contact Endowment Association development director Sandy Rupp at (316) 978-3807.