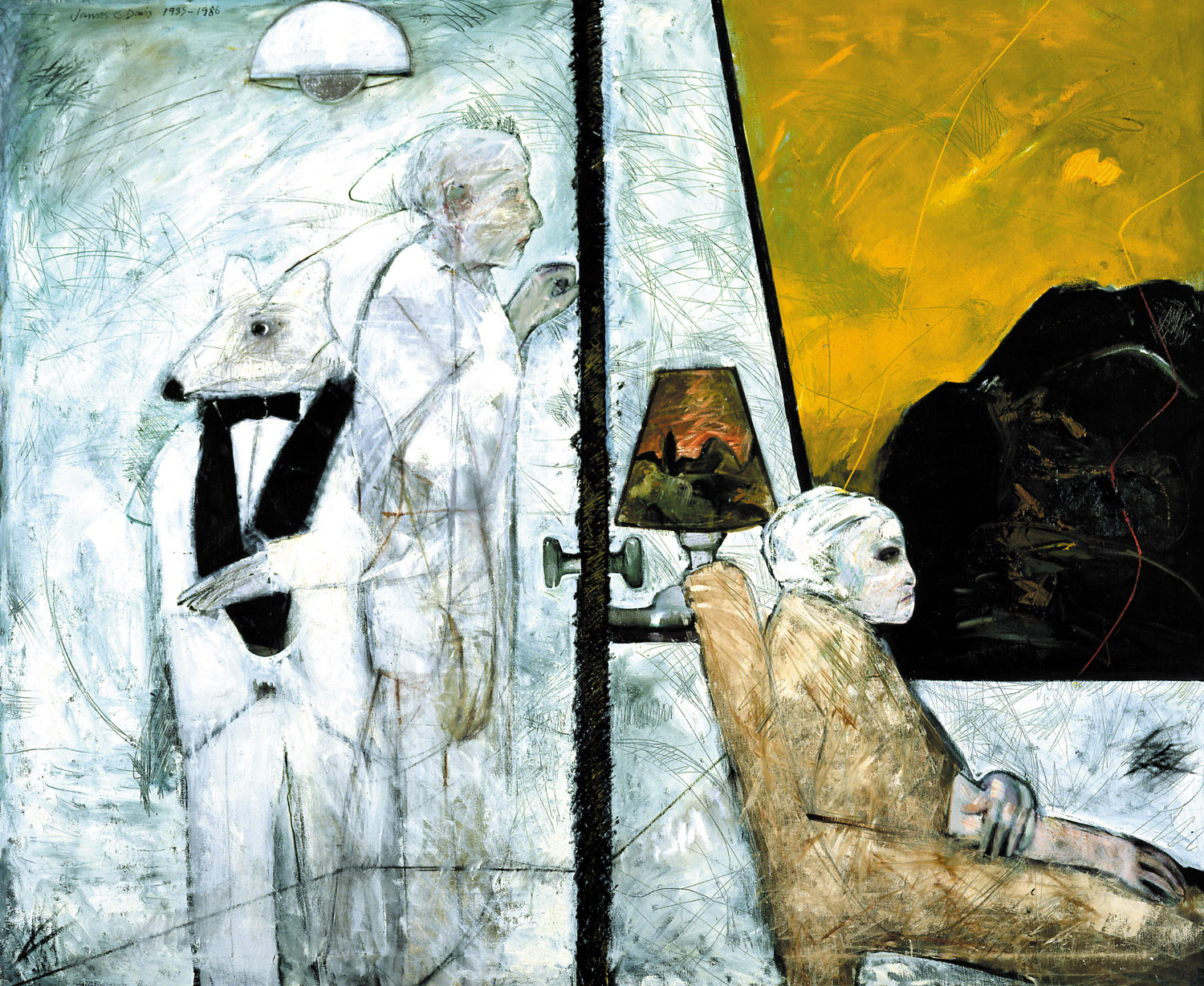

Another color I can instantly associate with the islands … is a gardenia white; a color like the underside of the giant tentacle I saw briefly wrapped around the rail on a stormy afternoon on the boat deck.

— From the artist's notes

The Cruise exhibition catalog, 1994

James G. Davis made this entry in a journal he kept during a three-week cruise he and his wife, Mary Anne '64, took to the South Pacific in the early 1990s. This fleeting vision from the periphery of reality, glimpsed from the corner of his eye, seems to sum up the way he sees the world.

For Davis, gardenia white — a color that more ordinarily calls to mind Dorothy Lamour with a gardenia adrift in her long black hair — became transmogrified into the color of a giant tentacle, an image classically associated with the horror film.

For at least as long as he has been painting, Davis has kept journals. Inevitably, observations from them appear in his work. "I see myself as a painter of our times, and like a lot of artists, I comment on the times we find ourselves in," he says. "I'm not making judgments, I simply paint what I observe. I use observations as metaphors to arrive at the real meaning of things, the reason for things being as they are, and if people look at one of my works long enough, they may discover that for themselves."

Davis is a prolific artist. Drawing upon a seemingly inexhaustible personal store of uneasy and edgy memories, visions, daydreams, nightmares, hopes, fears, perceptions, emotions and thoughts more than occasionally tinged or framed by a dark sense of humor, he has, over the span of his career, generated thousands of paintings, lithographs, etchings, woodcuts and collographs; by his estimate, he has produced perhaps 2,000 paintings alone. And in the process, he has created some of the most extraordinary and unforgettable works on the contemporary art scene.

"Jim has built a national as well as an international reputation. His work more than holds its own in comparison with other living painters of our time," says Robert Yassin, executive director of the Tucson Museum of Art. Davis' solo exhibitions number more than 55, his group exhibitions are too numerous to count, and his works are included not only in many private collections but also in the permanent collections of such world-class museums as New York City's Metropolitan Museum of Art, Washington, D.C.'s National Museum of American Painting, the Smithsonian Institution's HiRSChhorn Museum of Art and the Berlinische Museum, Berlin, Germany.

"Jim has built a national as well as an international reputation. His work more than holds its own in comparison with other living painters of our time," says Robert Yassin, executive director of the Tucson Museum of Art. Davis' solo exhibitions number more than 55, his group exhibitions are too numerous to count, and his works are included not only in many private collections but also in the permanent collections of such world-class museums as New York City's Metropolitan Museum of Art, Washington, D.C.'s National Museum of American Painting, the Smithsonian Institution's HiRSChhorn Museum of Art and the Berlinische Museum, Berlin, Germany.

For those who measure success by a different standard, Davis meets or exceeds the mark; his son, Turner, also is artist, explains, "Currently, Dad's larger paintings sell for between $20,000 and $45,000 apiece."

That's the art world's dollar-and-cents reality. But Davis' paintings forge an altered — or heightened — sense of reality that generates a different kind of resonance with the viewing public. "You're brought into this world of his that draws you back again and again. That alone sets him above many of his peers," says James Ballinger, director of the Phoenix Art Museum.

Michael Van Walleghen, who is a poet, Davis' long-time friend and professor of creative writing at the University of Illinois-Champaign, comments, "If I were asked to name a genius that I know, it would be Jim. He has a phenomenal ability to portray a reality that is about to change at any moment into something else. It hasn't yet changed, but it's going to, and not for the better. His world is full of ordinary objects we recognize, but it's by no means an ordinary reality."

No Ordinary Reality

Just as his work spans continents and his paintings fuse conscious and subconscious realms, so Jim Davis has called a number of worlds home. He was born in 1931 in Springfield, Mo. His mother died when he was only two. When he was 11, he began to draw during a year-long recuperation from an accident. He had been playing a game of Dare with friends when his right foot was crushed under the wheels of a slow-moving train.

Davis moved with his family first to Joplin, Mo., then Pratt, Kan., and finally to Wichita in 1944 because his father had taken a job at Boeing and they had relatives in the area. "We moved to Wichita by inches, it seems," he chuckles. "But Wichita was where I spent a lot of my formative years, and I have vivid memories from that time."

He dropped out of high school when he was 14 and spent the next several years traveling around the country and supporting himself with odd jobs; in Chicago he worked for a year at a toy factory painting the faces of toy gorillas. He drove tractors in the wheat fields of western Kansas and worked at hotels in Wichita.

During that time, his interest in art was reinforced by frequent visits to museums in Chicago, St. Louis and Kansas City. "I'd like to say art was my passion in those years, but to tell you the truth," Davis admits, "I was mostly trying to keep from freezing to death. I got an education from traveling around, but it was a different kind of education, that's for sure." By 1954, his footloose days had lost their appeal. "I decided I'd better get into something real," he remembers.

Davis returned to Wichita and enrolled at Wichita University. He wanted to become an artist.

While an undergraduate, he made the first of what were to be several trips to Mexico, where he discovered an artistic and psychic kinship with its people, artists and culture. According to Novelene Ross, chief curator of the Wichita Art Museum, "Beyond his own personal history, Jim weaves into his work a sense of the dark areas of the mind, which are particularly apparent in those cultures he has a special affinity for, such as those of Mexico, Spain and Germany."

While an undergraduate, he made the first of what were to be several trips to Mexico, where he discovered an artistic and psychic kinship with its people, artists and culture. According to Novelene Ross, chief curator of the Wichita Art Museum, "Beyond his own personal history, Jim weaves into his work a sense of the dark areas of the mind, which are particularly apparent in those cultures he has a special affinity for, such as those of Mexico, Spain and Germany."

Davis earned the bfa degree with honors in 1959 and promptly began graduate studies. The previous year, he and five friends had opened a downtown gallery, Bottega, which was their contribution to Wichita's small but oh-so-cool Beat Generation enclave.

"We were a pretty poverty-stricken bunch," Davis says. "We tied our pants up with rope, we ate once a day, and when we had an opening we took turns being the waiter who mainly served the rest of us."

During the spring semesters of graduate school, Davis returned to Mexico and the Yucatan Peninsula to steep himself in pre-Columbian art and to paint; 1962 was a banner year, because it was then that he finished the mfa degree and met Mary Anne Ludwig, who became the subject of so many of his paintings and, in 1968, his wife.

Turner Davis is unabashedly direct about his father's bond with Wichita State. "WSU saved my dad's life," he says. "He hadn't finished high school, but they let him in on probation. They probably couldn't or wouldn't do that today."

Between 1962 and 1967, Davis was either in Colorado painting, Mexico, or points in between. He remembers, "I had a great time. Those years were developmentally crucial to my art, but I was basically starving. I never went anywhere without my portfolio."

Deciding once again to "get real," Davis became a teacher of painting and drawing at the University of Missouri-Columbia in 1967 because it would allow him to be near his father, who was living just outside Springfield, and was in poor health.

After his father died in 1969, a full-time teaching position opened up at the University of Arizona, Tucson, and Davis eagerly accepted the job, for several reasons. He had liked what he saw in Arizona, having passed through the area many times on his way to and from Mexico. His good friend, artist Bruce McGrew '61, was teaching at the university. McGrew had been an undergraduate at WSU when Davis was in graduate school; they had become admirers of each other's work, and McGrew had been a member of the close-knit Bottega crew. And finally, Tucson was only 60 miles north of the Mexican border. "That proximity was attractive," he recalls, "But it's ironic that after I started teaching at the university, I couldn't break away to get down there much at all."

Davis was, in his own way, starting to put down roots. In 1970, he and several friends and artists bought Rancho Linda Vista, a run-down former dude ranch near Oracle, a town southwest of the Galiuro Mountains and just 30 miles northeast of Tucson and the university. Van Walleghen remembers, "At any given time, the ranch could have been described as a cooperative or a commune. It was an evolving experiment, depending on the mix of people. The amenities were minimal." Davis and Mary Anne lived, and continue to live, in one of the nicer buildings on the compound. And in 1971, Turner was born.

During the ensuing years, Davis successfully combined traveling, teaching and painting. Always the inveterate wanderer, he journeyed to England, Spain, Greece, Egypt, Italy and Germany as often as he could — but this time, with his family. His son says, "My father took me all over the world. Every summer we'd go somewhere new, visit the museums, get a sense of the culture. It was the greatest life imaginable for a growing boy."

Artistic Acclaim

Davis' reputation as an artist was growing as well. In 1979, he began to enjoy his first real commercial success, which arose out of a solo exhibition he had at the Riva Yares Gallery in Scottsdale, Ariz.; since then, Yares has become the primary U.S. gallery to represent Davis' work. In 1984, his growing reputation in Europe was galvanized by a one-man exhibition at the Hans Redmann Gallery in Berlin. And in 1988, the Tucson Museum of Art staged a 25-year retrospective of his work to honor his contributions to the Tucson art community as well as to contemporary American art.

Davis' success is a validation of his vision. Although not deliberately, he never became part of the New York/East Coast art crowd. Preferring instead to act out the role of the American individualist standing on any one of several untamed frontiers — or on the periphery of the art world — Davis has, comments Van Walleghen, "succeeded on his own terms." And in the process, he has become recognized as one of the contemporary American painters influential in returning the figure to art.

According to Ross, "Jim's work was shaped by the foment of American art in the 1950s, the reappearance of figuration in abstract expressionism, a reclaiming of the figure as a significant subject to frame social issues, and he in turn, and in his own singular way, shaped that movement."

Van Walleghen and Davis met in Wichita in 1966, and poet and painter immediately noticed similarities between their subject matter and their means of expressing it. "We found we were on the same wavelength," Van Walleghen says. "Our images are strikingly the same. They have the same resonance, the same surreal quality."

Having used a Davis painting on two of his earlier books of poetry, last year Van Walleghen asked him to do a cover painting for his next volume, The Last Neanderthal, because, he says wryly, "I knew it would be a congenial subject for him." And three of Van Walleghen's poems were included in the catalog written for Davis' 25-year retrospective.

This poet, which might be expected, and this painter both operate within a largely narrative framework to tell a story. However, time is seldom if ever linear in Davis' art. Ross observes, "Jim doesn't work within a literal narrative. Instead, he lays down a free association of objects and themes. He superimposes one moment of time over another and another, and he thus creates an incredibly complex and rich narrative tension." Yassin adds, "In order to deal with narrative you must start with some kind of reality, and reality necessarily involves the human figure. Purely abstract art may deal with the same concerns about the human condition that Jim deals with, but, finally, abstract art is only an arrangement." In other words, for Jim Davis, the medium is not the message.

While Davis does not regard technique as an end in itself, his technique is nevertheless remarkable. "Jim is a tremendous painter," Yassin remarks. "If you look at the surfaces of his paintings, you see a whole other level of beauty in the way he integrates his material. His control of the medium is sometimes absolutely amazing." And paint is not the only medium through which he excels. Ballinger observes, "Jim is best known for his paintings, but he should be just as well known for his lithographs. He's a wonderful printmaker — really, one of the best printmakers in this country."

Desert and Ocean

In 1993, after having taught at the University of Arizona for 21 years, Davis retired from his position as professor of painting and drawing, and he and Mary Anne bought a home outside Liverpool, Nova Scotia. "I guess I was used to going south all the time, so I decided to do something different," he explains. "I saw this place advertised in some home and garden magazine, we went up to see it, and we bought it on the spot. We're right on the Atlantic, right on the edge of the crashing waves. It's just beautiful."

These days, the Davises divide their time between the desert southwest of Oracle and the more temperate climes of Nova Scotia. They also still travel to Europe. According to Turner Davis, his father still works "at least several hours each and every day in his studio, whether he's in Arizona or Nova Scotia. He's always got several projects going at once, and he's always working on one or another or several at any given time."

This process of creation is very like the way he envisions and then renders each painting's story or moment. Very like the way in which time overlaps, weaves in and out, and bends back upon itself in the narrative. And very like the way his peripheral visions materialize in all their dreadful beauty on canvas for the whole world to see:

Arrived in Aukland, New Zealand. At the Anthropology Museum I did some drawings of a giant extinct Moa bird [which] materialized into a painting … I did this painting instead of an octopus in a domed bell jar. I am also thinking about the giant tentacle clinging to a rail, however.

— Final artist's note

The Cruise exhibition catalog