Station and Natural History Reservation in southwestern Sedgwick County.

Two hundred years ago, your eyes would have swept across a different landscape — a vista of grand distance, of gently undulating horizon and, except for the brilliant bursts of spring and fall wildflowers, muted colors.

No cattle, but the shaggy bulk of lumbering bison.

No new-green or harvest-gold wheat, but the prairie’s native grasses: big and little bluestem, Indian grass, sideoats grama and blue grama, grasses that entangled the fertile soil, keeping it in place despite the seemingly ubiquitous south wind.

No tree-lined rivers, but open waterways whose only shade came from scudding clouds and intermittent copses of cottonwoods that had gained rootholds along favored river bends.

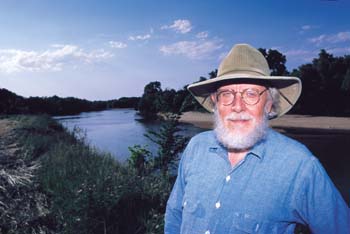

Today, at Wichita State’s Ninnescah Research Station and Natural History Reservation in southwestern Sedgwick County, Don Distler, whose German name appropriately enough means thistle, tramps a small band of visitors through knee-high grasses and forbs toward the south bank of the Ninnescah River. Along the way, the associate professor of biology identifies native plants as well as some of the exotics and aliens that have joined — and sometimes supplanted — species indigenous to the grassland communities that comprise central North America’s Great Plains.

“Look,” Distler says. “This is Maximilian sunflower. There’s spiderwort over there. Here’s western mugwort.” He snaps the top off of a mugwort plant and rubs the leaves between his thumb and index finger. “Smells like sage,” he explains, handing the forb to his visitors for inspection. For a moment the bittersweet smell of sage fills the air, yet the small herbaceous plant bears little physical resemblance to the better known sagebrush of the high plains.

“Many of these plants are native,” he explains, “like the milkweed here.” A bumblebee buzzes away from the plant’s top-heavy load of greenish blossoms. “The bumblebee is the milkweed’s only pollinator,” he adds, before turning his attention to a widely dispersed ground-creeping plant with small, white, morning-glory-like flowers. “That,” he notes, “is field bindweed. It was probably brought into the U.S. in the 1870s with red wheat. Bindweed is naturalized here now. It’s hard to get rid of and gives farmers all kinds of head-aches.”

milkweed.

Looking north from the south bank of the Ninnescah, which serves as the research area’s northern boundary, Distler points across the river to the line of cottonwoods, willows and other trees standing sentinel along the course of one of the three main rivers that drain Sedgwick County.

“The woods are encroaching,” he says, with only the merest sliver of disdain. “The prairie is maintained by fire. If you don’t have fire…” He lets the presence of the trees finish his sentence for him.

A Drop in the Ocean

Like a single blade in a once-vast sea of grass, Wichita State’s 330-acre Ninnescah research area is a part — however tiny and however altered — of the Great Plains, which encompass about 1.5 million square kilometers and contain the majority of the continent’s native grasslands.

There are three basic types: the tall-grass prairie extending from Manitoba south into Texas; the mixed-grass prairie stretching across Alberta, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Montana and North Dakota all the way down into Texas; and the short-grass prairie blanketing Saskatchewan and eastern Wyoming south into western Texas and eastern New Mexico.

Each type of prairie ecosystem is found in Kansas. Mixed-grass prairie, a transitional zone sometimes called the mid-grass prairie, runs through the heart of the state, with tall-grass to the east and short-grass to the west. Factors that determine which type grows in any given region include the amount of soil moisture, the season of precipitation and the relative humidity.

Evolving in the rain shadow of the Rocky Mountains, grasslands once dominated central North America, prompting Willa Cather to write in My Antonia, “The grass was the country, as the water is the sea. The red of the grass made all the great prairie the color of wine-stains, or of certain seaweeds when they are first washed up. And there was so much motion in it; the whole country seemed, somehow, to be running.”

The prairie, so often compared to the ocean, owes its existence at least in part to ancient, inland seas that ebbed and flowed over much of North America. Some of these seas were deep and cold. Others, including the last one, were shallow and warm. Called the Cretaceous Sea, the last inland ocean began its slow disappearance roughly 65 million years ago, its demise coinciding with the uplifting of the Rocky Mountains and the extinction of the dinosaurs.

Layers of old ocean beds, some of which had been almost totally eroded during times of earlier uplift, were slowly buried under tiers of stream-borne sediments, wind-blown glacial dust and volcanic ash. It was this eons-old, soil-creating web of processes that laid down such a fertile foundation for the later emergence of the prairie.

From his riverbank vantage overlooking the Ninnescah, Distler points out the gentle rise of the north bank and then — where the water moves fastest — the steep, quickly eroding south bank, which is banded in tones of brown, ocher, red and gray.

“See those red and blue layers of rock outcropping from the riverbank?” he asks. “That’s Ninnescah Shale. The blue shale was laid down when a deep sea covered the area. The red shale tells us there was a shallow sea here then. Blue, for no oxygen and deep seas; red, for oxygen and shallow seas. We’re looking at Permian shale that’s 240-290 million years old.”

The prairie is much younger. It did not come into its own until the end of the Ice Age, until after the earth had slowly warmed and the glaciers that once pushed as far south as northeastern Nebraska had retreated. Only then did it supplant the earlier forests, savannas, swamps and tundra.

Fire, wind, water and grazing animals then began their cultivation of the new grasslands, and for nearly 15,000 years the prairie, like the inland seas before it, has advanced and retreated across the heart of the continent. In its heyday during warm, dry interglacial times, the reach of these highly productive biological communities crested into parts of Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana and eastern Ohio, contributing immense value to watersheds and providing forage and habitat for vast numbers of animals, both small and large.

In recent times, the American bison, now extirpated from the wild in Kansas, has been pound for pound the largest prairie dweller, with dominant bulls weighing a ton, cows topping out around 1,100 pounds and calves weighing a full 65 pounds at birth. Their numbers on the Great Plains were nothing short of staggering, and estimates of the original number of bison roaming North America range as high as 70 million animals.

They were joined by fellow prairie grazers, moose, pronghorn, white-tailed deer, mule deer and elk; preyed upon by their only original enemies, wolves and grizzly bears; and scavenged by the black bear, mountain lion, bobcat, coyote and the larger raptors.

Smaller mammals abounded. The Virginia opossum, shrews, moles, bats, jack rabbits, cottontails, prairie dogs, squirrels, woodchucks, gophers, mice, rats, beaver, muskrats, foxes, raccoons, otters, skunks, weasels, ferrets, badgers and porcupines — all made their homes on the prairie.

According to reports from Wichita’s Great Plains Nature Center, 86 species of mammals are known to have lived within Kansas. But the number has fallen. In addition to Bison bison, six other mammalian species have disappeared from the wild in Kansas: the gray wolf, black bear, grizzly bear, black-footed ferret, mountain lion and moose.

Yet the state is still rich with wildlife. Along with 66 species of reptiles, 31 species of amphibians and legions of insects, 135 species of fish have been recorded and even more species of birds, 457, including Sturnella neglecta, the western meadowlark, which has been Kansas’ state bird since 1925.

Still standing on the south bank of the Ninnescah, Distler again points north, this time to the sandy flat that borders the river’s bend to the northeast. “Once in a while I let a friend of mine bow hunt carp here,” he says. “We’ll put the fish over there, where eagles congregate in the fall. I’ve seen fights break out between the eagles and the raccoons that come to feed.”

Carp and gar are both easily spotted swimming close to the river’s surface. “Ninnescah,” Distler notes, “is an Osage Indian word meaning clear water.” As a particularly large gar breaks the surface, he adds, “Those gar go back to the Eocene. They’re almost as old as the dinosaurs.”

He gestures down river. “The river washes out all kinds of things,” he says. “Along one bend downstream a ways, you can almost always find something interesting, a bone, a shell.” Often, the finds are echoes of the prairie’s lost diversity. Among the buffalo, deer and other bones he’s picked up, Distler once found the skull of a female wolf, a species that was last seen in Kansas more than a hundred years ago.

A Peculiar Beauty

Despite fascinating fauna, it has always been the steadfast, subtle strength of the soil-entangling grasses that characterizes the prairie — that and the eternal interplay between the two grand horizontals of land and sky.

In his Letters and Notes on the North American Indians, George Catlin describes the prairie this way: “Soul-melting scenery was about me. …the prairie…softening into sweetness in the distance like an essence. …this prairie, where Heaven sheds its purest light and lends its richest tints.”

John Charles Fremont, in Narratives of Exploration and Adventure, relates, “The grand simplicity of the prairie is its peculiar beauty.” And the Kansas painter John Noble offers this account: “You look on, on, on, out into space, out almost beyond time itself. You see nothing but the rise and swell of land and grass, and then more grass — the monotonous, endless prairie!”

As unbounded as the prairie seemed before 1850, its limits became manifest soon enough. In Sedgwick County, like elsewhere, change came in the guise of the European hunter, farmer and trader. C.C. Arnold, the first documented white settler to arrive in the county, rode onto this tract of the Great Plains in 1857 with a party of hunters and stayed.

John Ross, a farmer, came in 1860, and in the fall of 1863 J.R. Mead set up a trading post on the site of present-day Wichita. The county, as many Plains Indians tribes already knew, was a hunter’s paradise. Mead, on just one outing, is reported to have killed “330 buffalo, antelope and one elk,” according to William G. Cutler’s 1883 History of the State of Kansas.

Lying within the Arkansas River Lowlands of the Central Lowland physiographic province, Sedgwick County’s 1,000 square miles are drained by the Arkansas River, Little Arkansas River, Ninnescah River and tributaries of the Walnut River — and have proven to be fertile ground for agriculture, industry, oil and mineral exploration as well as city-building.

Today, the county contains nearly 16 percent of Kansas’ population, and Wichita is the state’s largest city with a population of about 255,000. The most heavily industrialized area of the state, the county is known for aircraft manufacturing. The processing of agricultural products and petroleum, metal fabrication and chemical manufacture are also key industries.

Farming and ranching, of course, are the region’s core enterprises — so embedded in the area’s history that one cannot possibly think of Kansas without also calling wheat and cattle, farmer and rancher to mind. As vital to economic progress as each of these undertakings is, together they share responsibility for diminishing the original prairie.

Now vastly altered by urbanization, agriculture and mineral exploration, prairie ecosystems, especially the tall-grass prairie, survive in only limited areas. According to The Nature Conservancy, 99.9 percent of the original tall-grass prairie has been lost in Manitoba, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, North Dakota and Wisconsin.

The percentages of decline in other tall-grass prairie states range from 99.5 percent in Missouri and Minnesota, to 90 percent in Texas. Kansas exhibits the least decline, 82.6 percent. (No comparative figures are available for Oklahoma’s tall-grass prairie.)

Distler turns away from the river and leads his visitors back toward a four-wheel-drive vehicle parked near the research station’s trailer. As they pile into the vehicle for a wider tour of the area, he talks about a few of the studies students and academic researchers are conducting. Research activity ranges, he explains, from documenting the types and numbers of birds spotted along the river, to plotting the abandoned channels of an unnamed stream that flows across the land as part of an investigation into stream erosion.

His own academic pursuits became entwined with this land almost two decades ago. In 1983 the former landowner wanted to donate 230 acres of her land, 205 acres of which had been tilled and planted as wheat fields, to a university willing to use it for research.

“I thought it was the sorriest piece of land I’d ever seen,” Distler remembers, adding it was surely the most “cow-burnt, plow-burnt piece of land in Sedgwick County.” For years, he had lectured in the classroom about the ways people have been abusing natural resources. Finally, the opportunity had come for him to develop a working field station — and to actually restore a tract of prairie.

He spent the first 10 years overseeing periodic, controlled burns and planting native grasses. As he drives his small party of visitors onto a small, bumpy road that runs along the perimeter of the old wheat field, Distler announces, “This is it, the restored prairie. It may be monotonous, especially if you compare it to mountains or the ocean, but it’s doing a job. It’s protecting the soil from erosion. And it has its own subtle beauty. We have eight species of grass and a few forbs here. We burn every one to three years. It’s interesting to watch how the elements — fire, wind, rain — play the prairie like notes on a musical scale. Different conditions bring out different tones. In wet years, big bluestem dominates. In dry years, it’s Indian grass and sideoats grama.”

Lost Ground

Not far from the eastern boundary of the research area, Distler calls attention to one of his more recent projects, restoring wetlands — an enterprise he began in his second decade of working with the land by plugging the small stream that meanders across 40 never-farmed acres. The water has pooled into the stream basin and along its tributaries, creating marshland that is a haven for wildlife. Muskrat, quail, turkey, mice and many water-loving birds have returned to the area.

Distler stops the vehicle so his guests can climb out and enjoy a closer look. “In the fall,” he relates, “we’ve had as many as five thousand mallards on these marshes.” In the intense white heat of this hotter-than-average spring day, no ducks swim in the pools. Only a lone blue heron stalks a meal in the shallow water, while at the edge of the restored prairie immediately to the west, a dickcissel sings out territorial warnings.

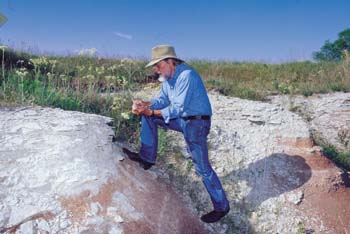

“We have a lot of red-winged blackbirds here,” Distler says, as he walks to an outcropping of rock that borders one of the pools. “Along with the big blue that’s here now, we often have green-backed herons and snowy egrets that come to feed on fish and frogs and salamanders.”

He pauses on the rock outcropping, waiting for everyone to catch up before explaining: “Remember seeing those red and blue layers of shale back at the riverbank? Here they are again.”

from its moorings.

With his boot, he worries a small slab of red shale free from its moorings, and with more of a nudge than a kick, he shatters it into bits.

“You’ve of course heard of the Dust Bowl and Oklahoma’s red dirt,” he adds. “That red soil originated from this type of shale. There used to be 54 inches of topsoil overlying the Permian bedrock of Ninnescah Shale. But after only 140 years of farming, we have from 18 to 24 inches left. It takes 200 to 1,000 years to produce one inch of topsoil, and we’re losing it at a rate of 50 tons per tilled acre per year. It’s clear we haven’t learned to use the land in a sustainable way yet. Right here, the soil is so thin it’s hard for anything to grow.”

He looks around and, pointing to a prickly pear cactus, says, “Some plants do find enough nutrients to live in incredibly thin soil. The perennial Opuntia macrorhiza is here. It likes rocky soils. And some annuals, like this yellow sweetclover, which originally came from Eurasia, make a go of it here, too.”

But the loss of soil is why — despite the $5,000 worth of topsoil he’s had trucked in and the soil-holding capacity of the native grasses he’s planted — the land will never be fully restored to its former state. To halt further soil erosion, Distler champions restoring prairie whenever and wherever possible.

His own restoration work, he classifies as “a labor of love” and adds: “When I first started out here, I had all these ideas about what I wanted to do, but the prairie knew what it wanted to do. So it tolerated me for awhile. I used to get frustrated about it and worry about it. I don’t anymore. I’ve learned. If I don’t understand it, at least I’ve learned to accept it.”

He may have learned to accept the prairie, but he and the other researchers who come to this tract of restored grassland in the corner of Sedgwick County, in the midst of the Great Plains, still strive to untangle some of its mysteries.

And its mysteries are as far-reaching and contrary as the prairie itself. Indeed, if a prairie could be said to have a dominant spirit, surely it would be that of the Cheyennes’ Coyote, a master trickster. So, in the illusion of limitlessness, there are limits. Yet the prairie remains illimitable.

As the author of PrairyErth, William Least Heat-Moon, writes: “The prairie, in all its expressions, is a massive, subtle place, with a long history of contradiction and misunderstanding. But it is worth the effort at comprehension. It is, after all, at the center of our national identity.”

Distler ushers his small band of visitors back to the vehicle for a short drive to another of the four different types of habitat found within the borders of WSU’s research area: the sand prairie. The multiplicity of habitats — restored prairie, marshland, sand prairie and riparian woodland — makes the area especially useful to researchers.

As the group hikes along a trail blazed by deer through a section of woodland bordering the river, Distler cautions to be on the lookout for poison ivy. He adds a broader warning: “We’ve got to take care of this world we live in. It’s our only life support system. We’ve got to have the oxygen the prairie produces. It cleans toxins from the air and purifies it. The grasses support the land from water and wind erosion. Grasslands are essential for our well being.”

The group emerges from the trees onto one of the sandy flats along the Ninnescah and into the ecosystem of a sand prairie. Sunflowers and grasses hold sway, and the tracks of various animals and birds are easily read in the sand.

Today, the most visible markings are turkey tracks and the sinewy trailings of beavers carrying branches riverward. But there are vestiges of others, not so visible. Although none scurries about this afternoon, Distler reports that this territory marks the westernmost range of the seed-eating kangaroo rat and adds that all kinds of things, mussel shells, for instance, are buried in the sand. “This river once had 20 different species of what are called unionid mussels,” he says. “Now it only has two.”

And it is from the flotsam left by the river along the slow curve of this sandy flat that, he says, he finds the most bones. Most of the large, recent ones are of deer; most of the older ones are of buffalo — plus that one wolf skull, which sits, somehow, as a visceral symbol of lost prairie ground.