“When I was at East High, I was just looking to graduate and start working at Cudahy Packing with my father and brother to make some money,” Cleo Littleton remembers. “I never thought about going to college. My family didn’t have the money for that.”

Coached by Ralph Miller, “Cleo the Cat” was tall and slender, graceful and quick, accurate and agile, and he had been the basketball star at East since he was a sophomore.

His graduation coincided with Miller’s becoming basketball coach at Wichita University, and he took Littleton along on full scholarship as his premiere forward to begin the glory days of Shocker basketball — a 20-year unparalleled-since reign of success wistfully recalled by all die-hard fans. Thus, in 1951, Littleton became the first black basketball player to play in away games in the Missouri Valley Conference, a distinction he held for two years. He also became a lightning rod for racial hostility both subtle and blatant. However, he says, “I was already used to that stuff. It was just part of my world.”

In 1960 there were 19,861 Negroes living within the city limits of Wichita. … Within the city, the Negro population is very tightly segregated. [In fact] Wichita is one of the most tightly segregated cities in the nation in terms of residence. In 1950, it was 14th from the top among 211 cities.

— Donald O. Cowgill, The People of Wichita: 1960, 1962

The history of discrimination in the United States is chronicled in incidents great and small, from the outrageous — murders, bombings and arson — to the merely offensive, and during the 1940s and ’50s, Wichita recorded its fair share of prejudicial treatment. For Littleton, injustice was up-close and personal. “After my sophomore year in high school, I didn’t suffer it as much as others did, because, as a stand-out athlete, I was one of the ‘OK’ blacks,” he says.

But in some classes at East High, blacks — Littleton included — were required to sit in the back of the room. They were neither permitted to go out for wrestling nor swim in the pool, a restriction that applied to the municipal swimming pool as well.

Blacks had to sit in the back or the balcony of Wichita movie theaters, and they could not eat in the front rooms of restaurants or at drug-store counters. Tennis and golf were reserved for whites. Virtually all restaurants placed limitations on black patrons; when East High teams traveled to away games, they were led to a back room or had to return to the bus to eat their food.

“Of course I didn’t like it,” Littleton admits, “but that was the way things were. I was a star, but I was still expected to know my place.”

“[Ralph] Miller says he thinks he did as much as any coach to break the color line. ‘I had black players on every team I coached,’ he said. … At times, Miller would put five blacks on the floor at East, even as fans called him a ‘Globetrotter’ or a ‘nigger lover.’”

— Bob Lutz, “Two Shocker Legends,” The Wichita Eagle, 2-7-93

“I came from an integrated neighborhood in Pennsylvania to play football for Wichita University. I began to coach after I graduated, and I got to know Cleo through Ralph Miller. There were all sorts of discrimination. I was amazed that black and white teammates on road trips couldn’t eat together. I knew that was the way it was down South, but I couldn’t believe it was that way in Kansas.”

—Ed Szczepanik ’50

At the University of Wichita, Littleton encountered the prejudices that by now had become fatiguingly familiar. Some instructors assigned the few black students enrolled at the time to back-row seats, and a young black woman he was dating told him that she had walked out of a classroom because the instructor, commenting on the weather, had said, “It’s raining pitchforks and nigger-babies out there.” Although complaints were lodged, the teacher was not required to apologize.

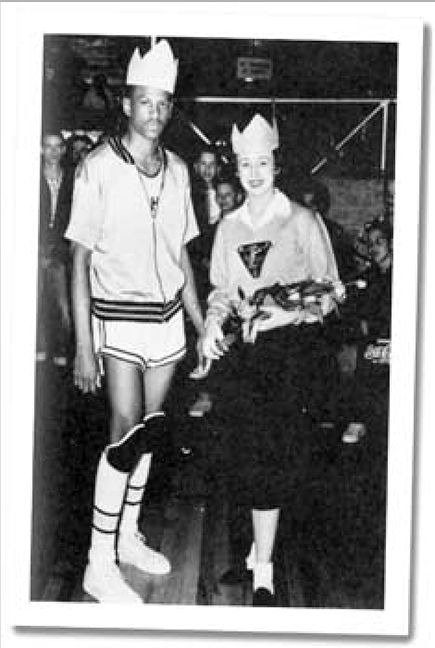

Jeannine Crowdus, as Wheaties Sweetie,

were crowned during the final home game

of the Shockers’ 1954 season.

During his junior year, Littleton was elected “Jack Armstrong” — the most All-American man on campus — and Jeannine Crowdus, who is white, was elected “Wheaties Sweetie” — the most All-American woman. Tradition associated with the honor involved a meeting at center court, a crowning and a kiss.

“Coach ordered me not to kiss her, and my teammates egged me on to go ahead and do it,” Littleton remembers, with a huge smile. “The crowd was applauding and cheering until it was time for the kiss, and then they went absolutely still. I just shook her hand. It was really funny — that was the one time that prejudice didn’t bother me.”

In the mid-thirties, William Jardine, then-president of the University of Wichita, answered a survey “concerning ‘the status of the Negro so far as his civil rights are concerned’ by noting that WU provided an equal opportunity for all races to work for a degree, that a ‘colored boy’ assisted Dr. Branch in the lab, and that blacks worked in the bookstore and on the student newspaper.”

—W. Craig Miner, Uncloistered Halls: The Centennial History of Wichita State University, 1995.

According to Ed Szczepanik, the sports arena was a promising model for racial harmony: “When you play ball, you’re friends for life.”

But, in the larger real-world arena, models were few and far between. “On road trips, they’d still have to bring food out to me on the bus,” Littleton remembers, “but a couple of the guys were great; they would bring their food, too, and eat with me.”

College basketball also involved overnight stays, and Littleton couldn’t get a hotel room like the others; he had to sleep over in a private home. His lifelong friend, Linwood Sexton ’44, who was the first black football player in the MVC, comments dryly, “Unlike what some white folks might think, that was not an enrichment opportunity. The concept of ‘team’ was damaged when one of us was physically separated from the others.”

Littleton also was called names — from the stands and from the floor — and vilified when he made a basket. During his senior year, the Shockers played, and lost, at St. Louis. Littleton recalls that as they were walking off the court “a kid ran up and spat right in my face. I shoved him back, just a little shove, and maybe 4,000 fans began hollering and coming after me. It flashed across my mind that I was going to be lynched. One of the St. Louis players, Dick Boushka, put his arms around me and said, ‘Let’s get you out of here, Cleo,’ and he shielded me to the locker room.”

When Littleton graduated from WU in 1955, he was an early draft choice for the now-Detroit Pistons; however, there were only three or four black players in the entire league, and none on the Detroit team. He decided against being a trailblazer again. Instead, he played for three years on a team sponsored by Wichita’s Vickers Petroleum Company in the semi-pro National Industrial Basketball League.

A coaching job might have been the next natural move for a former All-American, but, Littleton explains, “I never wanted to coach. Basketball — although I loved it — had been my ticket to a college education. I wanted to go into business.” He had unwillingly majored in physical education at WU. “In those days,” he recalls, “if your SATs were just average — and mine were —they made the decision for you that you would be a PE major. After my freshman year, I began taking as many business courses as I could. I graduated as a PE major, but I’d earned minors in business and economics.”

An analysis of Wichita’s 1950 Census of Population and Housing revealed that black males were largely employed in service jobs and as truck drivers, machine operators, and laborers, and that they were virtually unrepresented in such classes as professional, sales, and clerical.

— Donald O. Cowgill, A Pictorial Analysis of Wichita, 1954

“In 1957, [Wichita attorney Chester Lewis] began successful action against local corporations to remove racial barriers, including getting the Boeing Co. to hire African Americans in pre-production training programs, instead of only for janitorial or food-service positions.”

—Phillip Brownlee, “Wichita Civil Rights Efforts in National Spotlight,” The Wichita Eagle, 11-11-98

Littleton approached Vickers management in 1956 about a job within the company but was told that Vickers did not hire blacks to work in the office. Instead, Vickers offered to set him up in the service station business; after he learned the ropes, he could sublease a station from Wendelin Herman, a white man, who was opening a Vickers station at 13th Street and Grove. Six months later, Herman made him the manager of that station, and he subsequently subleased other Vickers-Herman stations at 21st and Burns, 9th and Hillside, and 13th and Hydraulic.

“Wendelin is a fine person — I call him my ‘white daddy’ — but the bottom line is I was a college graduate running four gas stations in the ghetto for a white man,” Littleton says, shaking his head.

“Blacks now have business opportunities that didn’t exist back then. Everyone understood that blacks could achieve only certain kinds of success. They could be doctors, lawyers, and teachers — and, of course, laborers and menial workers — but not accountants, supervisors, middle managers or clerical workers. At Vickers, Cleo’s opportunity was not to move up in the hierarchy but to sublease and pump gas at yet another service station.”

—Linwood Sexton, regional sales manager, Hiland/Steffen Dairy Foods Co., Wichita

By 1958, Littleton and his wife, Eloise, had saved $3,000 to buy some land in an all-white area north of the university. He explains, “I just wanted my family to live in a nice neighborhood. I had worked hard, and I was ready and able to build them a nice home.”

Neighbors protested, and Ralph Miller, who told Littleton he was concerned for the family’s safety, tried to dissuade him. “We’d been living on north Minneapolis,” Littleton remembers, “and Ralph told me we should stay down there where we belonged, which upset me. I told him, ‘I don’t play basketball for you anymore, and I don’t have to listen to you anymore.’”

It took Littleton five more years to save enough money to build their dream home, but, finding that the experience had “left a bad taste in my mouth,” he sold the land. They found a home on Magill, west of Rock Road, that they liked, but the owners would not sell to blacks.

However, the Littletons had a back-up plan; a white couple they were friends with bought the house and promptly sold it to them. About half of the neighbors were openly hostile, and quite a few soon moved out. The Littletons stayed. “Eloise and I have lived there for 28 years, raised four kids — Reginald, Mitchell, Robyn, and Barry — and we’re still the only blacks in that area,” Littleton muses. “Imagine that.”

“In 1963, Chet and I bought a home on north Roosevelt just beyond what was called the ‘Iron Curtain’—east of Hillside and north of 21st Street—beyond which blacks were not permitted to live. I posed as a white couple’s maid to be able to get inside the house to see if I liked it, and they bought the house with our money and deeded it over to us. When we moved in, all hell broke loose. We received threatening phone calls, our home was firebombed, and our cat was killed. In the fall, someone poured gasoline in the shape of a cross in the front yard grass and set it on fire.”

—Vashti Lewis ’71

Littleton toiled in the service station business for 21 years, deliberately making time to study banking in Lincoln, Neb., and to undertake a year and a half of bank training management at Wichita’s Union National Bank. For once, his skin color and education seemed to work to his advantage; in 1979, he was contacted by a group of Wichita’s black community members who were ready to challenge the permissible list of business opportunities.

They were opening a bank at the corner of 17th and Hillside; it would be the first minority-owned bank in the Wichita area, and they wanted Littleton to be its vice president of public relations. “We owned 48 percent of the stock, and we did real well,” he says with a rueful smile, “so well that the white guys and the one Mexican-American who owned the other 52 percent decided to sell. When the new group of whites came in, they gave themselves big salaries, and the money started evaporating. I got out just in time to receive maybe 6 cents on the dollar before the bank folded.”

“From the 1970s through the 1990s…white corporations began to compete for the black consumer dollar. The black hair-care products market, propelled by the success of Soft Sheen and Johnson Products, was targeted especially. Along with Motown, these were three of the leading black businesses in the 1970s and 1980s, and all were subsequently purchased by giant white corporations. … In 1992 black business revenues amounted to only 1 percent of the $3.3 trillion earned by all U.S. firms, the same as in 1987. … The number of black-owned firms increased from 424,165 in 1987 to 620,912 in 1992, but most of these businesses were very small — over 50 percent of black business in the 1990s had gross profits less than $10,000.”

—Juliet E.K. Walker, “Business and African Americans,” Africana.com, 1999

Undeterred, in 1982 Littleton started Litco Inc., his own general contracting business that handles construction, demolition, remodeling, roofing and concrete work. Litco was so successful that in 1991, Littleton brought his son Mitchell in to oversee much of the company’s operations; in 1999, Littleton began a second enterprise, Litco Products Distributor LLC, which warehouses and distributes general contracting products.

Finally, and for a change, Littleton was in charge. “I was partly interested in business early on because, as a black and an athlete, I got real tired of being told what I could and couldn’t do,” he says. However, as a black business owner, he met unexpected economic discrimination that even made being the boss difficult.

“The Small Business Administration set-aside program, for example, also counted women as members of a minority, so a lot of white businessmen figured out that they could set their wives up as heads of their companies and compete for those dollars,” Littleton comments. “And they did so, very successfully.”

The set-aside was subsequently revised to 5 percent for women and 5 percent for minorities, which meant blacks had to bid competitively against other blacks as well as all other racial minorities. Thus, he remarks, “That piece of pie gets really small. And now some people are trying to get rid of the program altogether on the grounds that it discriminates against whites.”

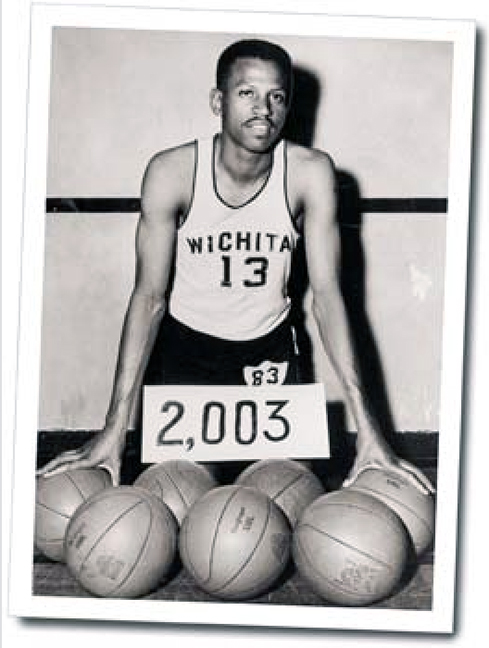

points scored in a career: 2,164. This summer,

he will be inducted into The Valley Conference

Hall of Fame.

“Opponents of minority business set-asides may succeed in unraveling a web of federal programs that were spun in the last decade. … A Supreme Court appeal…argued that incentive bonuses given to prime contractors for hiring minority-owned subcontractors to complete road construction are unconstitutional discrimination against white-owned firms.”

—Neil Munro, “Minority Set-Asides,” Washington Technology, 1-26-95

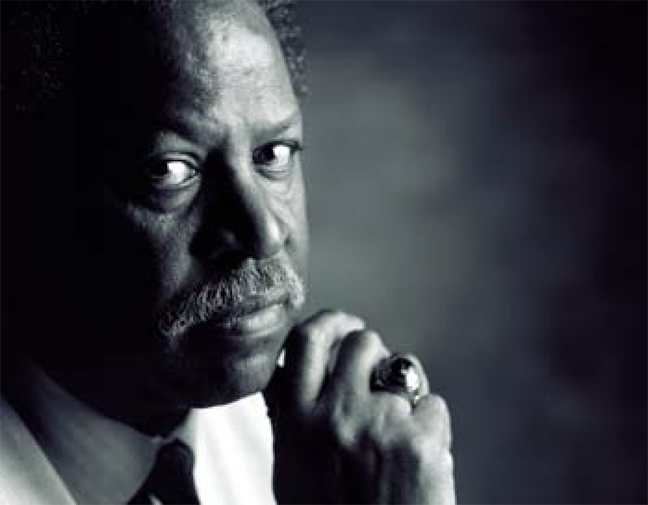

Littleton, who will be 68 in December, vows to be his own boss “until they put me in a box.” An avid Shocker basketball fan who hasn’t missed more than a dozen games since he graduated, he is coaching his 13-year-old grandson, Miles, who he says has the potential to revive the Littleton basketball legacy. “All my kids participated in sports until they were juniors in high school,” Littleton says, “and then they decided to find other things to be good at.”

Cleo Littleton still holds the Wichita State record for the most points scored in a career: 2,164. The only player ever to be named All-MVC four times, he is a charter inductee into the Pizza Hut Shocker Sports Hall of Fame and one of only five WSU basketball players whose numbers have been retired.

Last December, Sports Illustrated compiled a list of the 50 greatest sports figures of the 20th century from each state, and he was ranked #21 in Kansas. This summer he will be inducted into the MVC Hall of Fame in St. Louis.

Littleton is uncomfortable with such accolades. “My teammates played a big part in my athletic accomplishments, just as my heroes — Linwood Sexton and ‘Pappy’ Allen, my old schoolyard buddies — positively influenced my personal life,” he says.

In the same way, he hopes to inspire his grandson. “I see it like this,” he explains. “Miles can be better than I was, just like things today are better than they used to be for blacks. Not perfect yet, but better.”

Like Martin Luther King, Littleton has a dream — but one still chronicled in black and white.