Three days after Hurricane Rita dissipated, Gladys Alley ’75, a

retired nurse and trained Red Cross volunteer, left her home in

Wichita for chaos-stricken Louisiana.

Disaster swirled upon disaster. Fueled by warm waters in the Gulf of Mexico, Katrina made landfall in the early hours of Aug. 29, 2005, south of Buras, La., as a strong Category Three hurricane.

The storm devastated the Gulf Coast and shook the nation.

Katrina powered in a deadly wall of water, sweeping away towns, trapping tens of thousands of people, swamping rescue efforts for days.

Floodwalls in New Orleans engineered to hold back Lake Pontchartrain and surrounding waterways gave way.

Billions of gallons of water flooded 80 percent of the city, parts of which sit more than eight feet below sea level. From Louisiana to Florida, more than 90,000 square miles were declared a federal disaster area. Originally tagged a Category 4 hurricane at landfall, Katrina was downgraded by the National Weather Service to a Cat 3 storm more than a month later.

No matter the label, Katrina’s ferocity is estimated to be responsible for $75 billion in damages, making it the costliest hurricane in U.S. history. Worse, the storm killed 1,422 people, the most since the Okeechobee Hurricane in 1928 with its death toll of 4,075 — a number Katrina could yet nearly match. As of March 6, some 2,000 people remain unaccounted for.

Hurricane Rita followed Katrina by only a month. Formed Sept. 17, Rita was the 17th tropical storm, 10th hurricane and second Cat 5 hurricane of the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season. The storm first hit Florida after making an approach near Cuba and whirled on to flail Texas and Louisiana. A day before landfall, the resultant storm surge reopened some of the levee breaches caused by Katrina and reflooded parts of New Orleans. Rita caused another $9 billion in damages — and took six more lives.

Three days after Rita dissipated, Gladys Alley ’75, a retired nurse and trained Red Cross volunteer, left her home in Wichita for chaos-stricken Louisiana.

“I left for Baton Rouge on September 29,” Alley says. “An old Wal-Mart store was the Red Cross headquarters there. After orientation in the afternoon and an uncomfortable night spent at the Flannery Road Recreational Park Center, 12 of us RNs were deployed to Lafayette to work in the Cajun Dome, an arena for the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. Our home for sleeping was Christ Gospel Church where about 60 workers were housed in Sunday school rooms. I chose a small room with five cots that was decorated with kites that children had made.”

Alley was assigned to health-care services in the Cajun Dome, where some 4,000 evacuees were being housed. In early September, the arena, normally used for athletic events and concerts, sheltered as many as 6,000 people.

“When we arrived, we went through intense security,” Alley recalls. “There were armed guards and military police everywhere. There were people in cots everywhere there was an inch of space — hallways, corners, doorways, the convention hall, on the three floors of the dome and, of course, the arena floor. There were families, singles, babies crying, children playing. Some of their faces shone with brightness, some with anguish, some with disbelief and wonder, some just staring into space.”

The health-services desks, Alley reports, were set up in one of the dome’s corridors. Surrounding the desks were tables for patients, or “clients” as Alley calls the displaced people she was there to help. “I saw many clients with numerous needs — headache, stomachache, dental problems, lost glasses. Many tearful people needed comforting.”

Alley and a fellow nurse, Dawn, were charged with completing and filing reports with the state of Louisiana and the federal Centers for Disease Control. “We spent hours cleaning up files and making and learning how to do our daily reports that had to be faxed to the state and to the CDC every morning,” Alley says. “They were monitoring if there may be a pattern of an illness that could spread.”

gone -- no schools, no bank, no post office,

no church. The cemeteries had tombstones

swept away, with open graves and some

remains showing," says Gladys Alley ’75, a

retired nurse and trained Red Cross volunteer.

On her fourth day in Louisiana, Alley met one of the individuals who was to touch her the most deeply during her three weeks as a Red Cross volunteer. “A tall, black man, Michael, came to the dome very distraught,” she relates. “During Hurricane Rita, Michael was working on a barge in Lake Charles. When he came home to evacuate, he thought his wife had already evacuated, but he found that a tree had fallen on their house and hit his wife in the head. He carried her for four miles to the hospital, where they told him she was dead. After she was buried, he slept and wept on her grave for three days and three nights. When he first came to the dome, he didn’t want to talk to anyone. We ended up sending him to the hospital. We hoped we would see him again.”

By Mon., Oct. 3, the population of the Cajun Dome had dropped to roughly 2,000. People were leaving for other temporary housing or returning to their own homes to begin repairs. Many of those who remained, Alley recalls, “looked so forlorn and without hope.”

Marty ’97 and Lisa ’97 Duplechain live in Carencro, La., where they’re raising their four children. He works as an RN in ICU at the LSU Medical Center in Lafayette, and she, a former early intervention teacher, is a stay-at-home mom. “We had no hurricane damage at our house,” Marty reports. “But after Katrina we had an influx of patients — busloads of people — at the hospital.”

Nearly a week after the hurricane, Marty, a former reserve first-baseman for the Shockers who also threw the javelin for WSU’s track team, was struck by the fact that people were still trapped on rooftops and living on highways and in overcrowded, dark, sometimes dangerous shelters in New Orleans. Evacuation efforts were ongoing — but those efforts weren’t proceeding quickly enough for most people, including Duplechain. He decided to do what he could about the tempo of action.

On his day off, after working a nightshift at the hospital, he, one of his cousins and a friend drove to the New Orleans airport, the hub of evacuation activity. “Basically,” Duplechain relates, “we helped unload the evacuees coming in by helicopter. There would be five helicopters in the air, waiting for the ones on the ground to be unloaded. They were funneling people in. It was all military, and they were doing a good job, but it was like they weren’t moving fast enough. We knew we were only there for the day, so we busted our butts — we tried to set the pace.” After about six hours, an official asked to see the three’s credentials. “We were busted,” Duplechain says. “But we transported between a hundred and a hundred-fifty people in the time we were there.”

More than 1.5 million people along the Gulf Coast were ultimately displaced by Katrina and the resultant breaching of New Orleans’ levees, causing a humanitarian crisis on a scale unseen in the United States since the Great Depression. Evacuees dispersed to more than 20 states.

In early October, despite a steady drop in the number of people sheltering at the Cajun Dome, Alley and other Red Cross volunteer nurses were often seeing more than 100 patients a day.

“We nurses assessed the clients, took their vital signs and if they needed something more than we as nurses could do, we referred them to a doctor,” Alley reports. “We were overloaded with counting statistics — so many files!”

By this time, Alley had taken professional note of a number of inefficiencies in health-services procedures. For one, she was spending too much valuable time on unnecessary paperwork.

“The doctors who were seeing patients were not with the Red Cross,” she explains, “so they weren’t supposed to write on our charts. I had to read their reports and write their findings on our charts. I think it’s time for some changes in Red Cross protocol, and I’ve passed this on to both our local chapter and national headquarters.”

But it was the activity — or lack thereof — of the Federal Emergency Management Agency that caught Alley’s true ire. “Some days the lines at the post office set up in the dome were very, very long, as people were expecting and hoping for their FEMA checks. Ha! The joke was ‘Where’s FEMA?’ There were no signs, and no one from the agency to be found — disgusting and embarrassing.”

amidst all the rubble and ruins, and wondered

if this lovely land could or would ever return to

what it was. My favorite memories are of the

smiling, grateful people who loved telling their

special stories," says Alley.

But such sour feelings were the exception rather than the rule for Alley, who was routinely out of bed — or cot — by 5:30 a.m. and at work at the Cajun Dome by 7. She recalls that Fri., Oct. 7, was a “fruitful day at work. I remember making early rounds and seeing a child nestled next to mommy, a baby on the other side. There were babies in makeshift cribs, and four adults having a Bible study while seated on the floor. Some people were off at work somewhere. Some were at breakfast. Most seemed happy and friendly. Many had brought a few things with them in the evacuation — dirty but well-loved stuffed animals, books, all kinds of things. That day, I remember one family was celebrating a child’s birthday. They had a cake and were singing Happy Birthday.”

And it was Oct. 7 that Alley and others at the Cajun Dome shared in a very special reunion.

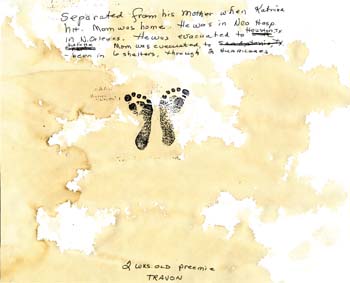

She explains, “A mother, husband and premature, 2-week-old baby came to our health-services desks. The mother had been separated from her baby in New Orleans, where he was in the neo-natal unit of a hospital. The baby had been evacuated to a hospital in Texas, and the mother had been in several shelters. She was on national TV pleading for anyone with information about the whereabouts of her newborn. She was in the Cajun Dome when the baby was brought to her! She was ecstatic — and didn’t want anyone else to hold her son for quite a while. She beamed with joy and relief. What a happy sight!”

Jerry Cranford ’64 is a former WSU associate professor of communicative disorders and sciences whose research interests focus on mapping the human brain. Now a program director at LSU’s Health Sciences Center in New Orleans, Cranford and his wife Fran make their home in Metairie — three, short blocks west of the infamously breached 17th Street Canal.

They are among the lucky few: Water through the breach flowed east. The Cranfords evacuated the day before Katrina to their daughter’s home in Memphis and sustained only minor damage to their own house. The Health Sciences Center, a complex that encompasses six schools, 12 Centers of Excellence and two patient care clinics, was another matter.

Located near the Louisiana Superdome, the complex was hit with major wind and flood damage. “The whole Health Sciences Center had to be closed,” Cranford reports. “We set up shop at LSU’s main campus in Baton Rouge, where we still are six months after the storm. I commute two to four times a week to teach classes.” Although no firm date can be set, expectations are for the New Orleans center to reopen this April.

Cranford adds that he’s buoyed by the fact Gov. Kathleen Blanco sees education as the key to long-term recovery: “From grade school to higher education, the governor is making education a priority. But this is still a disaster area. There are signs of recovery, but recovery’s a long way away — there’s still a lot of chaos.”

Among those displaced by Katrina were some 100,000 New Orleans college and university students. “Some of our students are living in cruise ships on the Mississippi River,” Cranford says. “About two-thirds of our faculty lost their homes. Some of them are now in FEMA trailers or rent apartments. In New Orleans, we lost about 200,000 homes. About a million people left, and only a relatively few have returned. Our whole environment changed.”

baby came to our health-services desks. The

mother had been separated from her baby in

New Orleans, where he was in the neo-natal

unit of a hospital. The baby had been evacuated

to a hospital in Texas, and the mother had been

in several shelters. She was on national TV

pleading for anyone with information about the

whereabouts of her newborn. She was in the

Cajun Dome when the baby was brought to her!

She was ecstatic — and didn’t want anyone else

to hold her son for quite a while. She beamed

with joy and relief. What a happy sight!” says

Alley.

By Mon., Oct. 10, fewer than 1,000 people still sheltered in the Cajun Dome. That day, Alley was pleased to see a familiar face among the residents. “The highlight of that morning was seeing Michael,” she says. “He’s the client who carried his wife four miles after Hurricane Rita and then grieved at her grave for three days. He looked so much better. He gave me a huge hug, then held both of my hands and prayed for about four minutes — a prayer of thanksgiving for all our help. This gracious, kind, well-spoken man told me he plans to relocate to Florida to make a fresh start. He is an inspiration to me, and I heard he was an inspiration to many of our residents, telling them not to give up hope.”

Two days later, Alley and the other volunteers learned they and their clients were to move out of the Cajun Dome and into a convention center next to the arena.

That Wednesday afternoon was spent relocating their supplies and records and setting up a new medical station in the convention center “right next to the escalator and amidst residents’ beds,” Alley says. “It was noisy as crazy.”

By Fri., Oct. 14, the center’s resident count was less than 500. “More and more people were moving out,” Alley notes. “To where, I didn’t often find out.”

That day, her Red Cross supervisor assigned her field work with a mental-health team. “We drove to the area of Cow Island to the relief distribution center there, which was filled with canned food and clothes. When the food truck came, we formed an assembly line and filled 80 styrofoam trays with food that we then took with us in a truck and a car. We drove to Pecan Island, stopping anywhere we saw people and offering them a hot meal. All were so happy that we came.”

Joe Williams fs ’81 owns Solar Control of Mississippi, a window-tinting company based in Ocean Springs, where he and his wife Tammy live. The parents of two grown children —Tony, a University of West Florida advertising graduate who works with his dad at Solar Control, and Janet, a student at the University of Southern Mississippi — the Williamses were building their dream house on the beach near Ocean Springs when Katrina struck.

The home, just six weeks from completion on Aug. 28, was leveled a day later. “Lost it all,” Williams says. “We rode it out at our old house and were okay there, but the new house was gone.”

The former WSU football player, who kicked for the Shockers in 1978-79 and scored an NCAA record-tying 67-yard field goal against Southern Illinois on Oct. 21, 1978, is looking to the future — and weighing the pros and cons of rebuilding on the beach.

In two fell swoops, Katrina, followed by Rita, changed the Gulf Coast’s economic and physical landscapes. The hurricanes literally redrew the shoreline and remapped the population in a massive rezoning of both natural and man-made environments. As many as 400,000 residents of southern Louisiana and Mississippi lost their jobs, this in a region that was already one of the poorest in America.

Shipping, the casino industry, tourism and petrochemical enterprises were especially hard hit. Gulf-area oil production, importation and refining were interrupted, which affected fuel prices. A tenth of all crude oil consumed in the United States and nearly half of the gasoline produced comes from refineries in Gulf-shore states.

Ecologically, the storm’s effects will need to be studied for years before a clear, long-range plan of action can emerge. Some experts, though, contend that the primary recovery goal should be restoring coastal wetlands because of their role as buffers against future hurricanes and storm surges.

Yet others believe cleaning up toxic spills should be the first priority. According to the U.S. Coast Guard, there were 44 oil spills in Katrina’s wake. This, combined with other chemical and biological contaminants set loose in the environment, has degraded not only human living conditions but also crucial habitat for sea turtles, manatees and countless other species. No fewer than 16 federal wildlife refuges and reserves were damaged by Katrina and Rita.

“There was devastation everywhere on Pecan Island,” Alley recalls. “The odor in the air was horrific, indefinable — I nearly threw up. There were checkpoints by military police all along the highways, which looked like cow paths. Homes were totally gone or boarded up. There were dead nutria and snakes everywhere, turtles crossing the roads. We went into the Sacred Heart Chapel, which remained intact, but all the pews were out in the yard while they were redoing the interior. Many people couldn’t clean their homes since there was little fresh water available. Everything had been covered with salt water. We saw a purple car buried, a ship crashed in a yard, shells of homes. House numbers were painted on boards where homes once stood.”

Pecan Island, roughly 60 miles southwest of Lafayette, and Cow Island lie within Vermilion Parish, a locale cited by the parish’s tourist commission as “The Most Cajun Place on Earth.” The coastal area is a unique blend of prairie, bayous, marshes and farm land. “Rice, sugar cane, cattle, crawfish and alligators are — or were — farmed there,” Alley relates. “And it’s known as a great place to go birding. I sometimes could hear beautiful bird songs amidst all the rubble and ruins, and wondered if this once lovely land could or would ever return to what it was.”

up friendships quickly -- all in

amazement at the chaos. I saw

beautiful, very resilient people in

Louisiana having hope when it

looked so forlorn," says Alley.

Even in its ruins, Vermilion Parish gave Alley an unexpected gift. “We drove onto a torn-up driveway, and a woman in her 40s came out from behind a pile of trash,” she says. “She was smiling and glad to see us. A man was with her, and they were so delighted to have meals. Dana and Scott are their names. Dana asked where we were from. When I said ‘Kansas,’ she said, ‘So am I — Wichita!’ We were so surprised. Then she told us her story of how she and Scott couldn’t evacuate because of trees blocking the road. She tried to describe the huge surge of water and how she held onto Scott’s hair since he couldn’t swim. They thought at any moment they were going to die. She is the only person I met who actually rode out the storm surge — and I can’t imagine how.”

Sat., Oct. 15 was Alley’s first and only day off. She and two other volunteers decided to drive to the town of Cameron, near the Gulf.

“Cameron was completely gone, from Hurricane Rita. Places like Cameron never got much news coverage, even though the damage was great. There was literally no town left, only a shell of a Hibernia bank with an ATM machine and vault sitting in the open all covered with salt. There was a gas station with pumps standing, a news stand with yellowed papers inside. We stopped at a cemetery with vaults opened and a few bony remains visible, headstones all in disarray. We could barely drive through the narrow, junk-filled streets. Hanging in a tree was a little girl’s pretty, ruffly dress, splattered with mud. There were many alligators dead beside the road. Hundreds of dead nutria. I doubt the town will ever be rebuilt.”

Back in Lafayette, Alley was closing in on the end of her stint as a volunteer. She continued making rounds, filling in charts and reporting statistics to the CDC and the state. She visited Avery Island, the famed home of Tabasco.

Recalling her last day at work, Wed., Oct. 19, she recaps her time in Louisiana, “What a great experience! The greatest part was meeting such wonderful co-workers who stuck together through thick and thin. The moon my last day was full and beautiful, and many of our psych clients were acting out. Many were concerned about where they will be going, as the center was set to close soon. God bless them.”

No one yet knows where the Gulf Coast and its inhabitants are headed in the long run. Alley, the Duplechains, Cranfords and Williamses are a few of the many simply working to get back from chaos.