some two dozen talented and skilled artisans, including many

WSU alumni who focused on the task of stencil design,

construction and application.

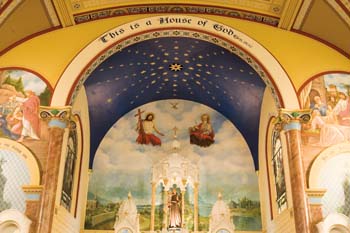

Whether the occasion represented sacred mystery or simple devotion, the anonymous person who in 1909 snapped a black-and-white photograph of the interior of St. Anthony’s Catholic Church captured an image that, some 100 years later, would prove to be indispensable to that church’s renovation.

Discovered in the church archives, the single over-exposed and time-faded picture of the imposing main altar and immediate foreground discloses little useful detail, especially of the intricately multi-patterned and -colored stenciling that comprised St. Anthony’s kaleidoscopic canopy, arches and walls.

The challenge for restorers, however, was clear: Use the photograph to resurrect both the image and spirit of the church. Located at 256 N. Ohio, St. Anthony’s is the oldest Catholic church in Wichita. Construction was finished in 1905, and the church was dedicated on Sept. 17. Known as the “German church,” the building boasts spectacular stained-glass windows that were designed and handmade in Germany, shipped in pieces to Wichita, and assembled and installed by the same German craftsmen.

The windows feature mostly German inscriptions, and the building itself exhibits classic German-Romanesque elements.

The Immigrant Church

Today, St. Anthony’s serves a largely Vietnamese congregation. Facing a fundraising challenge, the members of the parish, as well as people from across the nation, donated $675,000 for the upcoming renovation effort. “It’s safe to say that every family, every member, gave something,” declares Robert Hartman, church member and chair of Restoration 2005. “And, while families have moved away, this was their parents’ church, so the response was overwhelming.”

The project had been planned for some 10 years, and the goal was to finish the renovation in time for St. Anthony’s centennial anniversary. Infrastructure repairs ranged from waterproofing the foundation to installing new wiring and lighting to repairing a leaking roof, including considerable water damage to the interior.

A Wichita Landmark

In preparation for the impending major work on the interior, committee members sought bids from several national firms, ultimately selecting Wichita’s own Art Effects LLC, a restoration and decorative painting company co-owned by Robert Elliot ’92 and his wife, Tracy Sloat-Elliot.

“We’ve been in business for 11 years,” comments Elliot, “and we worked for 10 of those years to get this job. I couldn’t have been more elated.”

In the meantime, Elliot had kept more than busy creating artistic masterpieces in the Wichita area and elsewhere.

He and an ever-changing cadre of artisans constructed such marvels as the faux marble light-box pilasters at the Warren Theater East; the painted plaster finishes at Healing Waters Day Spa; major renovations for St. Mary’s Church in Ellis, Kansas; and the nearly three-acre “Pride of the Plains” exhibit for the Sedgwick County Zoo, which features carved and painted imitation rocks. Elliot’s “elsewhere” includes work for Miami’s Four Seasons Hotel, numerous homes in Florida and the cruise ships SS Zenith and Sea Breeze.

The St. Anthony’s commission was an honor and a responsibility. “We were entrusted with the care of a building that was not only historically important but a landmark, both to the Catholic community and the city,” Elliot recalls. “We had to do it right.”

Accordingly, he assembled a crew of perhaps two dozen talented and skilled artisans that incidentally included WSU alumni Katherine Faulkner ’81/94, Vanessa Fulton-Plaster ’06, Debbie Walterscheid fs ’81, Greg Stuever fs ’77, Tanya Merritt ’90, Jeff Zimmerman ’05, Joanna Pinkerton ’05, Majella Brown fs ’98 and M. Jane VanMilligen ’77, author, graphic artist and calligrapher who died July 17, 2005.

Design, Pattern, Color

The photograph of the church’s interior was digitized so that various sections could be computer-enlarged and studied, which was especially essential for replicating seemingly endless permutations of stencil patterns.

St. Anthony’s ubiquitous stencil work functions as more than pretty embellishment; it is the single feature uniting the church’s many diverse interior elements: the four altars and their crowning murals, the 15 stained-glass windows, the stations of the cross, the sundry statuary and the six oval paintings on the groin-vaulted ceiling.

“Over the years, the entire original design of the church had been either removed or repainted,” Elliot reports, “perhaps beginning in the 1920s and certainly by the early ’40s.” During the war years, for example, the parishioners may have wanted to lower St. Anthony’s profile by erasing German influences.

And during the 1950s and ’60s, they modernized. Ultimately, everything was painted over to conceal ongoing water damage. “We had to strip away a lot of incompatible features and a lot of paint,” says Elliot, “to find our way back to the earliest elements.”

Beyond that lay the problem of figuring out the original colors from the black-and-white image. Elliot and his design team did a color analysis, coupled with best-guess intuition, which was backed up by some serendipitous physical evidence: “When a couple of radiators near the main altar were removed, we discovered some old untouched stencil patterns,” recalls Hartman. “But the colors — dark brown and maroon and green — weren’t particularly attractive.”

Just as there have been advances in photography, so there are now many more color choices, which allowed the artisans to remain faithful to the first colors while vastly improving them.

Tap, Tap, Tap

The stained-glass windows needed no restoration, and the re-creation of the murals and ceiling paintings was left to a Pennsylvania artist. Elliot and his crew thus could concentrate on the arduous task of stencil design, construction and application plus other repairs, an undertaking that ultimately took 11 months.

“It’s hard to say how many stencil patterns we made and were working with,” Elliot muses. “There were probably 30, but then there were modifications, and multiples. Some stencils were as simple as one color, and some involved as many as seven colors, and each required being registered to the next, and the next, and so on.”

Katherine Faulkner, an artisan who also worked as a member of the stencil design team, says that one of their goals was to try to be as faithful to the original designs as possible.

“Some patterns were, thankfully, easy to figure out, but so many of them were blurred, or so unclear, or so washed-out, or simply out of that old photograph’s field of vision,” she recalls, “that it was impossible to pin them down. So I would extrapolate a design, show it to Robert, and go back to the drawing board if I needed to.”

Elliot observes that, whatever their level of complexity, all stencils have one thing in common. They are applied with a brush whose bristle pattern is less than a half-inch wide.

“You’re not actually making brush strokes,” he explains. “Rather, you’re tap, tap, tapping a color on, building it up, going over each color three to five times to build them all up to equal density.”

Stenciling therefore involves hundreds upon thousands of half-inch hand-taps. When Elliot wasn’t doing exacting stencil work, he was re-creating the extraordinary faux-marble finish of the church pilasters.

For Art’s Sake

Joanna Pinkerton also was one of the stencilers. She has vivid memories of the parishioners: “They were so gracious, so kind, so thankful we were bringing their church back to its former glory.”

But she has equally vivid memories of her aching back: “The first day was really fun, but by the third day I was feeling muscles I didn’t know I had. The working positions were so awkward that I was taking ibuprofen before I went in so I wouldn’t be sore! But I couldn’t wait to go back the next day.”

pretty embellishment. It is the single feature uniting

the church's many diverse interior elements: the

four altars and their crowning murals, the 15 stained-

glass windows, the stations of the cross, the statuary

and the six oval paintings on the vaulted ceiling.

Faulkner remarks, “I think we got a sense of what the original artisans went through, a kind of collective memory of stiff necks and aching shoulders, but also of their dedication and joy at what they were accomplishing.”

Debbie Walterscheid’s son represents the fifth generation of Walterscheids at St. Anthony’s and whose ancestor, Johann Walterscheid, is memorialized on one of the stained-glass windows. “I was primarily a stenciler,” she says, “but my favorite task was bronzing and gilding. I bronzed a lot of the main altar — the finials, the capitals, the railing, the chairs, the lectern — and then we used 23-karat gold to gild certain features so that they’d gleam when the light hit them. It was tedious, time-consuming work, but I loved it.”

Elliot and his crew occupied St. Anthony’s on the Monday after Easter Sunday. Pews were removed for refinishing, chairs were set up in the basement for services in the interim, and a labyrinth of scaffolding was erected for the artisans.

“All that work by hand made for slow going,” says Hartman. “But we knew that the church was going to be magnificent once it was finished.”

The Truer Colors

The re-dedication of St. Anthony’s occurred on Dec. 14, 2005. Elliot says, “I think it’s the most beautiful incarnation of the church, period. It originally reflected the classical German tradition, which was brown, dark and somber. Now it’s a joyful place, full of light.”

Miraculously, a simple black-and-white photograph revealed the truer colors of St. Anthony’s image and spirit.