jazz station that serves the New York City area. "I was playing

jazz, r&b, Jefferson Airplane, Cream, Thelonius Monk and

Miles Davis. We were new, the voices were deep, and the

music resonated."

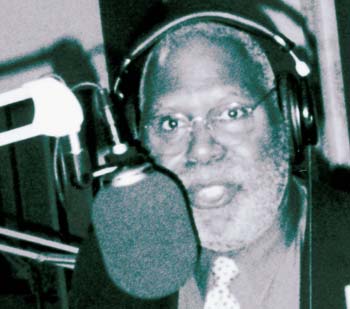

Thurston Briscoe ’74 has witnessed — and helped create — radio history.

As a disc jockey on KMUW in the 1960s (when he was a student) and ’70s (in his formative professional years), he saw the nature of FM radio transform from student laboratory to viable commercial enterprise.

In the 1980s, he was present on the ground floor of Morning Edition, a show that, since its inception in the ’70s, has become an integral part of National Public Radio’s daily programming.

Morning Edition, as any public radiophile knows, is memorable for its in-depth coverage of the ordinary people at the heart of daily world events.

Although Briscoe left the show some years ago, he has not wandered far from NPR, nor has he left radio.

Today, he is program director of WBGO in Newark, N.J., a consistently top-rated jazz station that serves the New York City area: “I’m having a ball doing what I’m doing. We are the most-listened-to jazz station in the country. What more could I want?”

“WBGO is considered the jazz station in New York City,” says NYC-based jazz guitarist Alex Skolnick, whose recent CD Goodbye To Romance: Standards For A New Generation received four-and-a-half stars in the jazz bible, Down Beat. “It’s an important part of being a musician in New York. If you play jazz, you have to listen to BGO.”

WBGO is one of the rare stations in commercial radio today that have kept a unique identity, one that both reflects and influences listeners. Often, numerous stations are owned by one company, resulting in formats that have little variety in the sounds listeners hear on radio stations from city to city. Briscoe notes that many of his early radio memories are tied to stations that stayed ahead of trends and remained in touch with the audience they were serving.

In the late 1950s, AM (which stands for amplitude modulated) radio signals traveled the distance between Mexico and Great Bend, Kan., where a young Thurston Briscoe would listen attentively: “There was this invention called transistor radio,” Briscoe recalls. “There was a black-operated soul station in Jackson, Mississippi, and you could hear a lot of James Brown. He wasn’t always on other stations and that made that station really special. The jocks were talking about rock, they were talking about soul, but they were also talking about what was going on at the local high school. The communities came alive.”

There was a special tenor of hope during those times, Briscoe notes. “Artists were speaking to people my age. Black and white music were coming together. The Civil Rights movement was happening. You could watch American Bandstand and see black kids dancing beside white kids,” he says and adds in a jazzlike flourish: “There were people saying that none of that would last — and then, suddenly, we all found the world transformed.”

Briscoe’s personal world was also transforming as he made his way to Wichita to study speech therapy and broadcasting at Wichita State. “Radio had been my lifeline to the real world,” he says. By his second semester, he’d started working at KMUW, putting reels of tape on machines and learning all he could about radio. It didn’t take long before he let it be known that he was interested in doing a jazz show.

But Wichita already had a jazz show on a competing station, so Briscoe started spinning classical music, waiting until the moment came when he could play the music he most loved. He became the voice of KMUW on Saturday nights.

But he found himself unable to decide between his studies and his passions. His hours at the station and a growing interest in theater left little time for studying — and he found himself on the outside of the university. “It was a bad time not to have a student deferment,” he says. Briscoe left for the Army, though he would be back in Wichita and back on air in time to see the birth of a new era in radio.

No Static At All

In 1970, FM radio was the awkward new kid in town struggling to find its voice. AM signals could travel long ranges at low power, but the waves were vulnerable to interference from telephone lines, tall buildings and other obstacles. The solution was FM (frequency modulated signals).

FM had existed since the 1930s, mainly as a place for stations to spill out into once the AM dial had grown too crowded. Post World War II, most FM programming consisted of simulcasts of content from sister stations on the other dial.

A mid-1960s mandate issued by the Federal Communications Commission prohibited AM stations from simulcasting more than half of their programming on FM. Early FM stations focused on small but loyal audiences (country, rhythm and blues, jazz and gospel).

This shift also birthed a second golden age for fans of rock ’n’ roll, the era of the album-oriented rock (AOR) format. Suddenly, songs with controversial lyrics that ran longer than four minutes and that often proved difficult to categorize became the lifeblood of FM.

Thurston Briscoe notes. And

changes were coming fast and

furious in the late 1950s and

early 1960s. “Suddenly,” Briscoe

says, “We all found the world

transformed.”

Briscoe, at this time, had landed back in Wichita and taken a post at WKFH FM spinning combinations one is unlikely to hear on contemporary radio: “I was playing jazz, R&B, Jefferson Airplane, Cream, Thelonius Monk and Miles Davis. We were new, the voices were deep and the music resonated. It lasted about nine months.”

The station, he says, was about more than music, about things outside mainstream culture, both of which may have led to its demise. “We had to do interviews in those days. We would go out and talk to these street missionaries, young kids, born-again Christians who were out working with [homeless people]. I think many [people in the area] thought of us as gutter freaks.”

“FM was something you really didn’t expect people to listen to, which meant that you didn’t even try,” says Jack Mitchell, professor of journalism and mass communication at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Mitchell’s own tenure at NPR in Washington, D.C., came to a close not long after Briscoe’s began. “FM became the medium of the counterculture.”

By 1971, Briscoe was back at KMUW, playing records but feeling somewhat out of touch: “I was doing AOR there on Saturday nights. Once we got past David Bowie, I started to lose it. Elf, I didn’t understand. Alice Cooper was an anomaly, and along the way there was Black Sabbath. It eventually got to the point where I couldn’t tell one band from another, and I said that on the air one night and bowed out.”

After graduating in 1974, Briscoe found himself in Eugene, Ore., teaching radio to students at a community college and learning about ethnic and political groups living and operating in the Pacific Northwest. “It was fascinating to learn about the origins of the Black Panther party in Eugene, a town that doesn’t have that many black people — probably more than Great Bend, but still,” he says and laughs.

His time in Oregon corresponded to the early days of NPR. A 1967 congressional act allowed for the creation of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting in order to encourage the growth and development of noncommercial radio. It was to develop into a nationwide network of noncommercial stations that would focus primarily on news, though according to Mitchell, who was the first employee of NPR, this was more easily said than done. “It was just an idea,” he notes, “and not a very well-formulated one.

It had to be built from the ground up. But the advantage was that we started with a weak set of stations and were therefore able to define public radio. We were dealing with nonbreaking news. We did background feature stories on the assumption that you’d get your breaking news from the networks and come to us for the sidebars and reflections.”

In the mid-1970s, Briscoe received a CPB grant for minority broadcasters that allowed him to hone his skills as a producer. During the time that Briscoe had the grant, a group of broadcasters who were developing Morning Edition for NPR happened across the country.

He made connections and was eventually invited to Washington, D.C. “I became a resident producer. It was like going to Mecca, the Vatican.” A few months later the people that he’d worked with out there called and said, “We have openings. Would you like to apply?”

Two weeks later, he had a new job and a new home. He stayed 10 years, until 1990, and became a senior producer — and although he stayed with Morning Edition, he worked on Jazz Alive, a live jazz and performance show that was the precursor of Jazz Set With Dee Dee Bridgewater, of which Briscoe is executive producer today.

When he left D.C., he returned to his first love, jazz radio, and has been at WBGO ever since.

A Companion Unobtrusive

Since the late 1970s, radio has changed. While many predicted its death with the advent of television and, to some degree, the Internet, radio has survived and learned how to thrive on new voices and new viewpoints.

The number of NPR affiliates has grown exponentially over the past two decades; stations such as KMUW have joined Public Radio International in broadcasting global, not just national, news. Mark McCain, program director at KMUW, which went on the air as the first noncommercial radio station in Kansas in 1949, says these changes are all part of radio’s unique nature. “Radio is an intimate medium,” McCain says. “You’re connected with that person, even though there’s distance between you.”

That connection is something Briscoe has always appreciated. The wonder he felt as a kid when he tucked a transistor radio earpiece into his ear is still evident. Today, he says he’s happy to be working in New York City, where the sounds of jazz are alive and well. “New York is still the place for jazz,” he says.

It’s also a place — like FM radio — that has the power to draw all kinds of people with new ideas and perspectives, which is something else Briscoe has always appreciated.

As jazz fusion violinist Joe Deninzon notes, the key to New York and, perhaps, to radio as well, rests in those changing voices, changing faces: “The beauty of New York is that there are people from all over the world coming here every day of every year. That always breathes new life into both the music and into the city. Every time you think that it’s all died out, someone new comes along from somewhere like Wichita, Kansas, and blows everyone away.”

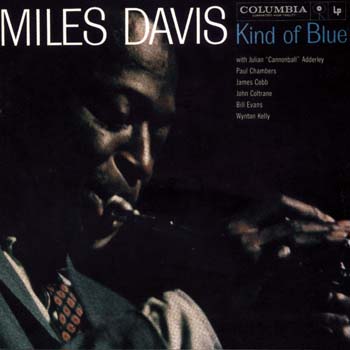

Without missing a beat, Thurston Briscoe responds in five words to this question: What’s your pick for album of the 20th Century? “Miles Davis, Kind of Blue.” More than 40 years after its release, it’s as relevant today as then. Here’s what a few contemporary jazz musicians have to say about Davis’ masterpiece:

Without missing a beat, Thurston Briscoe responds in five words to this question: What’s your pick for album of the 20th Century? “Miles Davis, Kind of Blue.” More than 40 years after its release, it’s as relevant today as then. Here’s what a few contemporary jazz musicians have to say about Davis’ masterpiece:

“It has had a tremendous impact on my musical life. There’s not a jazz or fusion musician I know who wasn’t in some way influenced by Kind of Blue.”

— Violinist Joe Deninzon, www.joedeninzon.com.

“Besides being one of the most musically groundbreaking albums of all time, Kind of Blue invokes a very special feeling when you listen to it. It is timeless, like the music of the Beatles, never losing its magic and continuing to reach new listeners.”

— Guitarist Alex Skolnick, www.alexskolnick.com

“Any musician who wants to prove their mettle should begin by transcribing everything on Kind of Blue.”

— Trumpeter/pianist Chris Opperman, www.oppymusic.com.