After nearly two decades with the Secret Service, the dark-suited, white-shirted WSU alumna standing watch over the President and First Lady has proven she’s worthy of trust and confidence — not to mention prepared for just about anything.

On the bright morning of Sept. 11, 2001, the scope of Rebecca Ediger’s career was about to change.

But at 6 a.m. she didn’t know that. A member of the Presidential Protective Division, she was looking forward to her early morning workout, which involves a six-mile run through the streets of Washington, D.C., a run she refers to as “inventorying all the monuments.” To prepare herself, Ediger ’76/83 typically listens to retro heavy metal, but on this morning she decided on a CD of hymns from the National Cathedral.

The run was peaceful enough, primarily because it’s the only time a PPD agent is without a pager. Back in her office, she received a call to turn on CNN because one of the World Trade Center’s twin towers had just been hit by a plane.

The second tower was hit while Ediger and other agents were in the Joint Operations Center continuing the daily White House Security Staff meeting. “At that moment,” says Ediger, “we all knew the first plane was not an accident. The country was under attack.”

Back in Newton, Kan., where her parents still reside, one of the local news stations initially reported that the White House had been struck. “I figured if I didn’t call, they’d assume I was okay.” Ediger pauses. “Now I know they could have also assumed that I’d been blown to bits.”

Like most parents, Donna and Milford Ediger worry about their daughter, but having a daughter in the Secret Service makes those worries more than a little unique. “We’re very proud of her,” says Donna Ediger. “Rebecca’s a very dedicated person, and she’s always been dedicated to whatever career she’s been involved in. We’re proud, but we worry.”

Expecting the Unexpected

the perfect personality for politics: genuine and

caring. But she's just as pleased to leave the

political limelight to others and stand at the

president's side.

For Rebecca Ediger, there’s really no such thing as “a typical day.” As the former deputy special agent in charge of PPD-White House Security, she can only say, “It was always busy.” She assumed this position the day after President George W. Bush’s inauguration, and for some time there were no serious incidents.

Then, on Feb. 7, 2001, a gunman opened fire toward the White House. Ediger was in a meeting in the West Wing when she received the page reporting a man trying to scale the south fence. “Was I surprised?” she says. “No. Were we prepared? Yes.” After a brief standoff, assailant Robert Picket was shot in the knee, disarmed and taken to a hospital for psychiatric treatment. Not only must agents expect the unexpected, they must be prepared at all times to deal with such situations immediately.

It wasn’t always this way for members of the Secret Service, who often refer to each other as “family.” Founded in 1865 as a branch of the Treasury Department, the original role of the Secret Service was to restore the public’s trust in the national currency, since, as of 1865, nearly one-third of the money supply in the United States was counterfeit.

However, by 1901 three presidents had been assassinated: Lincoln, Garfield (in a train station in 1881 four months into his first term) and McKinley (in 1901 by an anarchist while attending the Pan-American Exposition). With McKinley’s assassination, the function of the Secret Service was broadened to dual — but complementary — roles: investigation and protection.

Theodore Roosevelt became the first U.S. president to reap the benefits of such a system after Congress passed legislation in 1906 making protection a permanent Secret Service responsibility.

“After the 22 weeks of initial training it takes to be appointed an agent, the first three years of an agent’s career in a field office is considered on-the-job training,” she explains. “Agents are not considered for assignment to a permanent protective detail until they have from five to seven years experience, and field office agents do temporary assignments as detail agents for visiting foreign dignitaries and presidential and vice presidential candidates.

Ediger and her colleagues are also amused by the misconception that a Secret Service agent’s job is “glamorous.” The work certainly has its moments, but some of those moments are tedious — like standing post. “That means effecting security for any facility a protectee visits or resides in,” she says. An agent might find herself at a protectee’s private residence or, as when President Bush attended last year’s World Series, a baseball stadium.

And the weather tends to be unpredictable. “Standing post requires agents to be vigilant often under inclement weather conditions,” Ediger continues, “and 99.9 percent of the time you are standing.” She smiles, but not from nostalgia.

“Early in my career, I did several temporary assignments when President Reagan visited his ranch in the mountains of California. The first time I went was in March ’85 to work perimeter security doing 12-hour shifts. I remember the PPD agent taking us around hiking to each of the posts we would rotate to on our shift. It was a sunny afternoon before the president came in. This served us well.

“Every night thereafter, it was pitch black and it poured rain. When it wasn’t raining in the mornings, the fog was so thick you could only see a few yards in front of you. Glamorous?”

The Making of an Agent

that you will never become rich working

for the government," Rebecca Ediger says.

"However, in the Service you will go and

see places millionaires never do."

Being a Secret Service agent wasn’t a lifelong dream of Ediger’s. Her initial career was as a physician assistant, and shortly after graduating from Peabody High School, she started radiologic technology at St. Francis Hospital in Wichita and eventually went to work at the Hertzler Clinic while attending Hutchinson Community Junior College at night.

She was accepted into WSU’s physician assistant program in 1974. After completing the program in 1976, she worked for the chief of surgery at the Veterans Administration Hospital in Wichita.

The key motivation behind each of her career moves was wanting to do more — for other people as well as herself. And it was through the medical community that she began working her way toward Washington.

"While working in surgery, I became good friends with one of the surgical nurses whose husband was a Secret Service agent in Wichita,” Ediger remembers. “I didn’t even know we had Secret Service agents in Wichita back then, and this is 1982. Through my friendship with the couple, I began to learn a lot more about the country’s oldest federal law enforcement agency.”

The decision to leave health care wasn’t an easy one, but she flew to Dallas to take the Treasury Enforcement Aptitude test. “Coming out of the four-hour exam, I was convinced that I had blown it completely. I got the call the day after I returned to Wichita. Not only had I passed, but I had one of the highest scores.”

Ediger assumed her work with the Secret Service in the Oklahoma City Field Office in 1983 and remained there until leaving for Washington, D.C., in 1987. The office was located in the Murrah Federal Building.

On April 19, 1995, she returned to Oklahoma City after the bombing to help families of her coworkers — and to recover remains of those she knew.

“Everyone assigned to that office who was there on the 19th was killed,” says Ediger. “We lost six employees, four agents, the office manager and the investigative assistant. Even though I’d seen a great deal of trauma as a PA, nothing short of combat could have prepared me for the carnage.”

Yet her medical training has proven to be an invaluable asset. She has received commendations for saving several lives, including a U.S. attorney in Oklahoma City. “She even helped a protectee who was thrown from a horse in Texas,” recalls Ediger’s mother. “She also helps other agents and their families understand certain medical situations and diagnoses. She can put the things that doctors tell them into plain English.”

Those close to her agree that it is Ediger’s blend of compassion and dedication that make her who she is — and a successful agent. “She has a unique personality,” says longtime friend Keith Prewitt, deputy assistant director of Protective Operations.

“She has an uncanny ability to foster and forge relationships within the Secret Service. She is very well-known for being diplomatic and tactful. That’s just the kind of individual she is, and she has a personality you’d like to see appear more often in politics. She is truly genuine. Very, very genuine.”

Sacrifice and Rewards

Secret Service agent who helps direct protective services at the

White House.

Overall, Ediger’s work is extremely rewarding, but there are challenges and sacrifices. “You live your life around whomever you’re protecting,” she says. “That means, for the agent, missing birthdays, weddings, anniversaries. You have to be certain of what you’re giving up, and you have to believe in what you’re doing.”

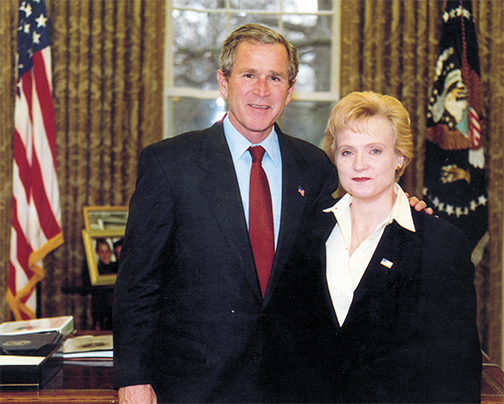

And she does. Her belief in and commitment to the job is evident to her family, her colleagues and the people she has protected over the past 19 years. On Dec. 13, 2001, President Bush presented her with the Distinguished Service Award.

Four days later, Secret Service Director Brian Stafford announced her promotion to deputy assistant director for the Office of Protective Research, a promotion that took effect on March 24.

“I feel so lucky,” she says. Yet as lucky as she feels to be part of the Secret Service, the Secret Service is also lucky to have her.

For Rebecca Ediger truly upholds and lives their motto: “Worthy of Trust and Confidence.”