On July 5, 1803, Captain Meriwether Lewis departed Washington, D.C., for Clarksville, in Indiana Territory, to meet with William Clark. Once together, they would lead an expedition, aptly titled the Corps of Discovery, across an unexplored continent to the Pacific Ocean in one of America’s greatest feats of exploration.

This May (2002), Bill Ard ’64 visited portions of the Lewis and Clark trail in western Montana, in the hope of finding a fuller understanding and a deeper appreciation of the famed corps’ three-year odyssey into the unknown.

Following a similar course of thought, WSU history professor Phillip Thomas often lectures about the expedition as Lewis, wearing authentic period dress. In expectation of the bicentennial of the corps’ trek — and in the spirit of Lewis and Clark, both zealous journal keepers — Ard and Thomas were willing to write it all down for us, so that we might have their thoughts to compare with those of Lewis and Clark.

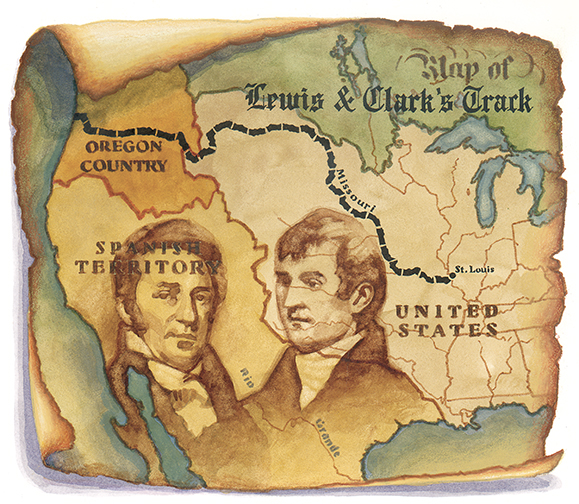

The expedition of Lewis and Clark spanned the years 1803-06 and covered a vast, unmapped area of the trans-Mississippi West — up the Missouri River and over the Rockies, down the Columbia River to the Pacific, and back.

The expedition of Lewis and Clark spanned the years 1803-06 and covered a vast, unmapped area of the trans-Mississippi West — up the Missouri River and over the Rockies, down the Columbia River to the Pacific, and back.

During the historic trek, expedition leaders Lewis, an Army officer serving as the private secretary of President Thomas Jefferson, and Clark, an experienced soldier and outdoorsman, made the first map of the area, collected invaluable scientific data about the flora and fauna of the recently acquired Louisiana Purchase territory and established the American claim to Oregon, Washington and Idaho.

Key among their hopes as they first dipped their oars into the muddy Missouri near St. Louis and headed their party west through uncharted Indian territory was finding an all-water passage to the Pacific. This was a hope they shared with President Jefferson, who firmly believed the destiny of the United States lay to the West. In the end, of course, they discovered there was no such route.

Yet some 2,000 miles into their 8,000-mile journey, as they spent the winter of 1804-05 at Fort Mandan in today’s North Dakota, they were still hopeful about finding the famed Northwest Passage. In particular, they were looking for the source of the Missouri and any of its tributaries that might connect with the Pacific.

One of the most fascinating chapters of the Lewis and Clark epic is their journey out from Fort Mandan into the wild and woolly territory that later became Montana and Idaho. It was at this juncture that the captains took on the French Canadian interpreter who brought with him his young Shoshone wife, Sacagawea.

The far west they would trek together was an area largely described through rumor and colored with hopes and tall tales. Huge, ferocious beasts (grizzly bears) were said to roam the land — and members of the corps even thought they might spot a woolly mammoth.

At Fort Mandan, Lewis spent much of April 7, 1805, overseeing the loading of the canoes that would continue upriver into the wild unknown and the keelboat that was going back to St. Louis, laden with plants, animals, artifacts and reports bound for Washington, D.C. At about 4 p.m., everything was ready.

Lewis wrote: we were now about to penetrate a country at least two thousand miles in width, on which the foot of civillized man had never trodden; the good or evil it had in store for us was for experiment yet to determine, and those little vessells contained every article by which we were to expect to subsist or defend ourselves. however, as the state of mind in which we are, generally gives the colouring to events, when the immagination is suffered to wander into futurity, the picture which now presented itself to me was a most pleasing one. entertaining as I do, the most confident hope of succeading in a voyage which had formed a darling project of mine for the last ten years, I could but esteem this moment of my departure as among the most happy of my life.

Almost 200 years after Lewis penned those words, Bill Ard and his two traveling companions, his brother Nick Ard and Dan Thompson, flew into Missoula, Mont., on May 22.

Ard wrote in his journal, “It was a cold, damp day, snowing in the higher elevations, raining in the lower. We spent the afternoon opening up a residence in town, renting a four-wheel drive Jeep and stocking up on items we wished to take with us.” From Missoula, Ard’s group traveled more than 1,000 miles in four days, searching out Lewis and Clark sites.

In contrast, 90 miles in four days was a windfall for the corps, whose passage through modern-day Montana and Idaho brought them up against two of America’s greatest natural obstacles, the Great Falls and the Bitterroot Range of the Rocky Mountains.

About their mountain route, Clark wrote: “thro’ thickets in which we were obliged to Cut a road, over rockey hill Sides where our horses were in danger of Slipping to Ther certain distruction & up & Down Steep hills … with the greatest dificuelty risque &c. we made 7 1/2 miles.”

Still, there were moments that raised their spirits, such as Aug. 12, 1805, at Lemhi Pass, where they found what they believed was the source of the Missouri.

After visiting the same spot on May 25, Ard wrote, “This is the tiny spring that Lewis and Clark thought was the real headwaters of the Missouri, in that it fed the Jefferson River. Their journals note that several of the corps stood straddling the rivulet. We did the same.”

We were inspired by seeing the actual locations written about in Lewis’ and Clark’s journals. We were immensely impressed at what they achieved on their great expedition, and we came away from our trip to western Montana with a more pronounced appreciation of the difficulties they encountered. The other realization was that without two strong, capable leaders the successful completion of the expedition might never have occurred. Our experience was an adventure for the three of us, and we will long enjoy remembering what we saw.

— Bill Ard

After months of fighting hunger, mountains, weather, rivers, animals and disease, the explorers caught sight of the Pacific on Nov. 7, 1805. Clark wrote, “Ocian in view! O! the joy.”

But he knew, come spring, they would have to be prepared to make the journey back.

The Lewis and Clark expedition gave the American nation vital information about the lands that lay beyond the Mississippi River, destroyed the myth of a Northwest Passage, began the initial assessment of the resources of the lands that could be found both in the Louisiana Purchase and beyond the Stony Mountains, revealed the number and complexity of Native American societies that would be found in the new West and ultimately opened those lands for settlement. Americans often have a passion for the past.

The expedition was one of the most exciting and defining moments in our history, and much of the expedition occurred in some of the most beautiful regions of our nation. It is quite natural then that contemporary Americans would wish to retrace this historic event by traveling along the well marked Lewis and Clark trail and celebrating in their modern odyssey the coming bicentennial of that epic journey.

— Phil Thomas

That epic journey, so alluring to the imagination, remains elusive to any final interpretation. Looked at narrowly, it can be seen as a failure. After all, Lewis and Clark didn’t find an all-water route linking Atlantic to Pacific. And what they did find was something that wouldn’t remain: an untamed land inhabited by Native Americans. Within only a few generations, the west was settled and the Indians pushed onto reservations — and into their own unknown. Furthermore, Lewis, who was often described as melancholic, killed himself at Grinder’s Inn in Tennessee in 1809, and Clark went on to lead a tumultuous political life.

But eyed with a sweeping view, the Corps of Discovery expedition is a timeless and awe-inspiring success — offering lessons in resilience, resourcefulness, luck, adaptability, patience, cooperation, trust and reasoned fearlessness, as America enters another time of great change and uncertainty.

— Contributing, Connie White

Check out the National Council of the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial’s website: lewisandclark200.org.