in 1959. WU's first anthropology professor and a

faculty member of what was then the sociology and

anthropology department, Holmes was a recognized

expert on Samoan life and culture. Over the course

of his 31 years at WSU, he spearheaded the

development of what has become an anthropology

department of international note. Holmes died

Aug. 31, 2010, in Wichita.

During the early years of Wichita State’s department of anthropology, the academic unit and its singular founder and first chairman Lowell Holmes were virtually synonymous – their histories interwoven. Sometimes, the more things change, the more they stay the same.

In the 1980s, cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead’s famed research on the social mores of adolescent girls in Samoa was under academic attack by New Zealand anthropologist Derek Freeman, who discredited her conclusions.

Mead (1901-1978), however, had an ally to defend her work: WSU professor Lowell D. Holmes, also a recognized expert on Samoan life and culture. “It was his finest hour,” says longtime colleague and anthropology professor Dorothy Billings of his defense, “and I told him that several times.”

Holmes, whose doctoral research was a methodological restudy of Mead’s fieldwork in Samoa, called her research “remarkably accurate,” recalls Billings.

Holmes, who conducted five research trips to Samoa during his academic career and brought Mead to visit WSU, wrote: “Mead was better able to identify with, and therefore establish rapport with, adolescents and young adults on issues of sexuality than either I – at age 29, married with a wife and child – or Freeman, ten years my senior.”

Had Holmes been less honorable, Billings says, he could have “sold her down the river.” But he wasn’t, and he didn’t.

Honor was part of the groundwork that Holmes, who passed away Aug. 31, 2010, used to build Wichita State’s anthropology department, which today continues his legacy through the multifaceted work of a veteran faculty of seven full-time members and the educational outreach of both the Lowell D. Holmes Museum, a resource its namesake was key in establishing, and Lambda Alpha, the national honors society that he began.

Holmes, who, like Mead, was a cultural anthropologist, arrived at the University of Wichita in 1959 from Missouri Valley College, where he had started his teaching career after earning a Ph.D at Northwestern University. An assistant professor, he was the university’s first anthropology teacher and a faculty member of the WU Sociology and Anthropology Department, a common marriage of disciplines in those years.

His introductory course, General Anthropology, quickly became a popular offering, filling Wilner Auditorium with 500 students – at 8:30 a.m. no less. Holmes was a most likeable and compelling teacher, says John McBride, a cultural anthropologist with interests in linguists who began teaching anthropology at WSU in 1965, joining Holmes and Karl Schlesier, who came to WU in 1962.

Certainly, McBride reports, the department grew because of Holmes’ efforts, but it also should be understood that because of the culture and the times of the 1960s and 1970s, anthropology itself was a college topic in vogue with students, especially those looking for an introductory class to fulfill a general education requirement. Thus, it was fortunate for the department’s growth that Holmes’ years and the popularity of his discipline dovetailed.

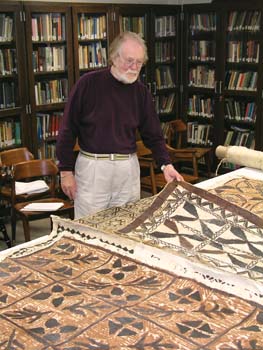

A lifetime scholar, Holmes often retreated to a university library carrel for research and class preparation. A photo in the 1966 Parnassus shows an intense Holmes diligently preparing notes for class. The same yearbook also recognizes him as an outstanding faculty member, the first of a number of honors. Two years later, he received the Kansas Regents Excellence in Teaching Award.

The plaudits were well deserved, say peers. “He was a fabulous teacher,” recalls Arthur Rohn, professor emeritus of anthropology who retired from WSU in 1999. “He was a good speaker and well organized, so students really liked taking his classes.”

Seven years after coming to WSU, Holmes came up with the idea to build a museum of anthropology. “He got a small grant and a hammer and nails and put it all together,” Rohn says. Born the Museum of Man, the museum that today bears Holmes’ name exhibited a variety of artifacts from the American Midwest and Southwest in a single room on the ground floor of McKinley Hall. To be sure, it helped that Holmes had several hundred pieces from his personal collection with which to lay the museum collection’s foundation.

Another one of Holmes’ initiatives at WSU was Lambda Alpha, a national honors society for anthropology students. Lambda Alpha, a name derived from the initial letters of the Greek words logos anthropou, meaning the “study of man,” is an organization whose purpose is to develop research and scholarship in anthropology.

Steady growth in student enrollment in anthropology led Holmes to lobby for a department separate from sociology. Donald Cowgill, who chaired the joint department, along with other university administrators, agreed to his proposal in 1966. The WSU Department of Anthropology had three faculty members: Holmes, Schlesier and McBride.

Two years later, its first female professor, the often colorful and always outspoken Dorothy Billings, was contacted to join the department. “They needed someone in a hurry, and I was eager to come home,” says Billings, who was in Australia studying for her Ph.D at the University of Sydney. She and Holmes had the same general academic areas of expertise – peoples of the Pacific and primitive art.

Billings, whose classroom subjects include cross-cultural psychology, theory and method, and millenarian movements, has taught for more than 40 years at WSU. These days, she teaches on a half-time basis and has recently developed curriculums relating anthropology to peace studies and international understanding. In May 2000, she received the President’s Distinguished Service Award, after being nominated by her peers in the WSU Faculty Senate.

The late 1960s and early 1970s were a robust time for the department. Financial resources were plentiful, and rising enrollment fueled course demand. If any problem was in place, it was signing on doctoral-level faculty, says Rohn, the department’s first archaeological anthropologist. “It was hard to find folks,” he recalls. “We had to hire warm bodies with the promise they would finish their Ph.Ds.”

When Rohn arrived in 1970, only two anthropology faculty members held doctorates, but over time that changed to all faculty members.

Rohn succeeded Holmes as chair of the anthropology department, yet Holmes’ departmental influence remained strong. “He founded the department, he founded the museum, he was its most popular teacher,” Rohn says. Holmes continued to teach and conduct research, and he acted as the department’s senior member by offering invaluable guidance to his junior colleagues.

Rohn served as anthropology chair until 1976 when he went on sabbatical. McBride then took up chairman duties, later switching academic disciplines to teach business. He is now associate professor emeritus of finance, real estate and decision sciences.

Also in 1976, Donald Blakeslee, an archaeological anthropologist who had been smitten with the discipline during a summer student trip to digs in Montana and Wyoming, was hired. Specializing in the archaeology of the Great Plains and Midwest, one of Blakeslee’s current projects is finding and researching the trail that the famed conquistador Coronado took during his exploration in what is now the United States.

A firm believer in hands-on experiences for his students, Blakeslee gets them out in the field as much as possible, and each year leads a wilderness field trip to Yellowstone National Park.

As interest in anthropology continued to grow, the department’s cramped – and scattered – offices became barely sufficient. Most professors shared offices in an old house, long since torn down, on the south side of campus. Relief came in the late 1970s when staff and faculty were able to move to McKinley Hall.

At the same time, the department not only expanded its range of classes, but also its “classrooms,” as field research endeavors increased. In the timespan from the 1970s through the early 1990s, Rohn secured more than $1 million for field research projects.

Funding came from numerous entities, including the Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Kansas Gas & Electric. Rohn says he was “quite aggressive” about going after funding because of the importance of students being able to gain field experience useful in their post-graduate studies or their careers.

Clayton Robarchek, WSU professor emeritus of anthropology, joined the department in 1985. A highly experienced field researcher, he held interests in Amazonian ethnology, medical anthropology and psychological anthropology, among other topics.

With his wife, Carole, he spent almost two years among the remote and fierce South American Waorani tribe. One result of their scholarly adventures is Waorani: The Contests of Violence and War. Like Holmes and Rohn before him, Robarchek also served the department as chair; he retired in 2008.

In 1989, a young Danish scholar, Peer Moore-Jansen, joined the department. As a biological anthropologist, Moore-Jansen expanded the department’s reach and scope, and gave it a higher public profile by assisting in local criminal investigations and providing TV interviews on subjects such as evolution and Kansas’ science curriculum.

Much like Holmes, Moore-Jansen proved himself to be a skilled teacher as well as talented scholar, receiving several teaching awards and building the department’s resources, most notably a forensics laboratory.

Moore-Jansen’s research has led him into a variety of subjects, including mortuary analysis and demography in eastern Europe, morphological variation in the human tibia and other skeletal elements, as well as analyses of vehicular fires and their effects on human bones.

A number of his studies have been conducted at an eight-acre site called the Skeleton Acres Research Facility northeast of Leon, Kan.

“Dr. Holmes was a real mentor to me,” Moore-Jansen says. “He was very supportive and very inclusive – not imposing, so I had the greatest respect for him.” In 1990, at the age of 65, Holmes retired and was awarded emeritus status. He also received the 1990 National Distinguished Teaching Award from the National Association of Student Anthropologists – and shortly thereafter the Museum of Man was re-named in his honor.

After retiring, Holmes gave full rein to his passion for sailing, building boats and playing jazz on his alto sax, which he had taken up at the age of 16. His love of jazz extended to writing about it; he co-authored Jazz Greats: Getting Better with Age.

“I’ve been a jazz musician all my life, so it was a labor of love,” he said in an interview about the book given just before his retirement. Jazz Greats features interviews with older jazz musicians, many well into their 80s, all of whom were musically productive and creative.

Holmes, too, retained his creative and intellectual vigor, continuing to publish and work on his Samoan research and staying connected to the university. As Moore-Jansen recalls, “Lowell would stop by and talk. We never went to lunch or anything like that, we would just chat. It was very comfortable.”

At about the same time, the department’s second-senior professor, Karl Schlesier, retired. A prolific writer who has penned 56 scholarly papers and six books, including the 1987 The Wolves of Heaven: Cheyenne Shamanism, Ceremonies and Prehistoric Origins, Schlesier visited the arctic slopes of northern Alaska, the central Pyrenees of France and many other locales for his fieldwork.

The noted anthropologist, who now lives in Corrales, N.M., is considered part of the Cheyenne’s extended family and takes part in tribal ceremonies. He also has been called upon to testify as an expert witness on two federal court cases involving the Cheyenne Nation.

After Schlesier’s retirement, the department signed on Robert Lawless, a veteran cultural anthropologist with a diverse background. Lawless’ research subjects range from the survival strategies of urban street people, to the headhunters of the North Luzon Highlands. His recent studies have focused on Haitians in Florida and Haiti. Lawless, who served as department chair for several years in the 1990s, also has served as undergraduate coordinator.

In 1999, the department made a major change when it moved from McKinley to Neff Hall. The move, which Rohn spearheaded, consolidated all of the department’s offices, classrooms and display spaces into one building for the first time. It also greatly expanded the department’s space, especially for its museum, which moved into the area formerly used by the university’s computing center.

Also in 1999, Jerry Martin ’68, one of Holmes’ former students, was hired as the museum’s permanent director. Martin was not only interested in developing the museum; he wanted it to serve as an educational tool through training students interested in museum studies. The museum continues that function today, and pays students a stipend for their work.

While the museum houses a number of notable collections, it is best known for its world-class Asmat art. Barry ’72 and Paula Downing of Wichita funded a 2001 expedition led by Martin to the Asmat region of New Guinea, in the Papua province of Indonesia.

Noted for their woodcarving, as well as their history as headhunters, the Asmat also are known for their veneration of ancestors. The privileged team – WSU was the first university in 40 years allowed in the area for the purpose of collecting artifacts – returned with nearly 950 Asmat objects.

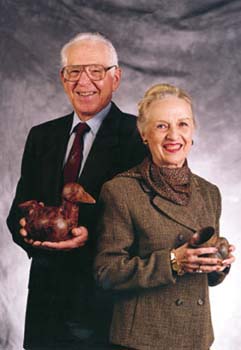

Over the years, the museum has attracted many friends and supporters, including Wichita businessman and former WU student David Jackman, who, before his death Jan. 27, 2009, donated to the anthropology department through the WSU Foundation a major gift, one that Moore-Jansen calls “unprecedented financial support.”

One aspect of the gift that particularly excites Blakeslee is the launch of a visiting scholars series. This semester, the department scheduled three speakers and, as Blakeslee puts it, “the students get to rub shoulders with some really interesting people.” Finding a way to bring prominent speakers to WSU was always important to Holmes, who once even had Mead’s antagonist, Derek Freeman, speak on campus.

Yet nothing was more important professionally to Holmes than his students, and he had an immeasurable impact on many of them. Some, including Jon Wagner ’67 and Susan M. (Colcher) Vehik ’69, followed in his footsteps. “As I near the end of my own career as an anthropologist, I fondly remember Lowell Holmes as the person who got me started,” says Wagner, professor of anthropology at Knox College in Galesburg, Ill. “A marvelous teacher and a fine man, my hero still.”

Vehik, associate professor of anthropology at the University of Oklahoma, also credits Holmes for launching her life’s work by persuading her to switch her major from geology to anthropology. She says she has always been glad to have followed his advice.

Even a non-major reflects on Holmes’ influence. “I became acquainted with Dr. Holmes my sophomore year at Wichita State,” writes Greg Rohloff ’75, a journalism graduate. “I had not chosen a major, although I was certain it would not be anthropology. One of his first lectures was the presentation he described as his mandatory sales pitch as department chairman.”

Holmes didn’t sway Rohloff’s choice of majors, but he taught him that learning occurs not only when paying attention to what one is already interested in, but also when listening to what someone else is passionate about. “For that, Dr. Holmes was a difference maker.”

Holmes had big plans for his academic discipline at WSU when he arrived some 52 years ago. Today, the museum he built literally by hand is at the top of its class in the world of Asmat collections; its peers are the American Museum of Asmat Art in St. Paul, Minn., and the Michael Rockefeller Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

The honors society Holmes began produces an annual publication that is now distributed to 170 chapters throughout the United States. And Holmes’ philosophy of anthropology (after Franz Boas’) still functions as the department’s operating principle.

Steadfast in practicing a holistic approach to anthropology, balancing its four subfields: archaeological, cultural, linguistic and physical, Holmes “believed in that very strongly, and I agreed with him 100 percent,” Rohn says. “The department has retained that approach to this day.”

WSU’s anthropology department continues to mature and grow. Back in 1980, there were 34 students with declared majors in anthropology, according to the WSU Office of Institutional Research. In 1993, the number of anthropology majors was 50, and in 2008, that number had risen to 92, according to a report prepared for the Kansas Board of Regents by Moore-Jansen.

To paraphrase one of his conclusions: The anthropology program at WSU, past and present, has offered and continues to offer great and diverse opportunities to our students.

Thanks, in no small measure, to Professor Holmes.

The David and Sally Jackman Visiting Scholars Series

David and Sally Jackman were lifelong supporters of Wichita State and the anthropology department. Through the years, they donated land, cash and artifacts. After Sally’s death in 2002, David continued his relationship with the university he had attended during the 1937-38 academic year and bequeathed $4 million to the WSU Foundation for the David and Sally Jackman Endowment for Anthropology. He died Jan. 27, 2009. The endowment funds graduate student support, fellowships, research assistantships and, new this season, a visiting scholars series.

David and Sally Jackman were lifelong supporters of Wichita State and the anthropology department. Through the years, they donated land, cash and artifacts. After Sally’s death in 2002, David continued his relationship with the university he had attended during the 1937-38 academic year and bequeathed $4 million to the WSU Foundation for the David and Sally Jackman Endowment for Anthropology. He died Jan. 27, 2009. The endowment funds graduate student support, fellowships, research assistantships and, new this season, a visiting scholars series.

The inaugural series featured three public lectures, in addition to classroom talks by the visiting scholars. Sam Gill of the University of Colorado presented the first lecture, “The Primacy of Dancing to Culture and Life,” on March 14, 2011. Rebecca Golden Timsar of Tulane University delivered “The War God and the Warriors of the Niger Delta,” which covers her research on the resistance movement against oil companies and the government of Nigeria by young men in the Niger delta region, on April 7, 2011. She also spoke about Doctors Without Borders.

The third and final presentation in the series is slated for 7 p.m., Thursday, April 21, 2011, in Hubbard Hall, Room 209, where Shaista Wahab will present her film “Afghanistan Unveiled: Obstacles & Opportunities for Afghan Women.” After the fall of the Taliban, Wahab traveled to Afghanistan, where she listened to women tell their stories of struggle and survival and their hopes for the future. Based on her videotaped interviews, the film deals with the centuries-old subjugation of Afghan women.