Many people wander through life, unencumbered by passion for anything in particular. Then there are those who, from an early age, develop a consuming interest in the field to which they are destined to devote their life's work.

Many people wander through life, unencumbered by passion for anything in particular. Then there are those who, from an early age, develop a consuming interest in the field to which they are destined to devote their life's work.

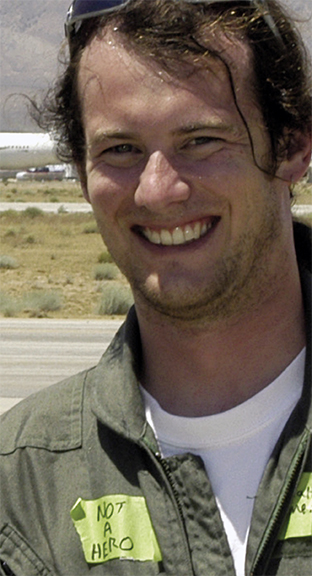

Matt Stinemetze '98 belongs firmly in the latter camp.

As project engineer at the Mojave, Calif.-based aerospace firm Scaled Composites LLC, the builder of SpaceShipOne (SS1), Stinemetze is now professionally immersed in his childhood obsession with "anything to do with airplanes," as he puts it.

"I always dreamed of flight," he says. "My dad was interested in aviation so I was, too. I always had model airplanes, right from the get-go. Dad would take us to air shows, and he took us to airports to watch gliders." His father, Tom Stinemetze, now city zoning administrator for McPherson, Kan., remembers well his son's penchant for building — and customizing — model airplanes.

"We had models around the house since day one," the elder Stinemetze says. "Matt never liked to put a model together the way the manufacturer designed it. We got into balsa wood pretty quickly. He enjoyed that a lot more than building a kit someone else had designed. He just seems to have a natural knack for it."

The Stinemetze family lived in Hutchinson then, and when the Kansas Cosmosphere opened in 1980, young Matt was among the first schoolchildren to visit the nascent space center. His enthusiasm for aviation quickly expanded to include flight beyond our atmosphere. "Really early on I had decided I wanted to do stuff with airplanes," he says, but "when I was a kid, going to the Cosmosphere, I got interested in space."

In the mid-1980s, he moved with his family to McPherson, where his fever for flight burned as hot as ever. As a teen, he seriously considered joining the U.S. Air Force, but decided on the advice of a friend to give WSU's aerospace engineering program a try.

Stinemetze threw himself into his studies at Wichita State, but after a time grew dissatisfied and unsure of his course of action. "I thought about getting out of it. I was disgruntled with school," he says. "I've always been an art lover, and I toyed with the idea of doing something else."

It was the advice of his then-girlfriend (now wife) Kathlene "Kit" Bowman '98, with whom he worked in the composites lab at NIAR, that ultimately set him back on course. "Kit suggested I talk to Dr. Miller," he says. He took her up on it. "A lot of people in aerospace don't want to talk about it off-hours. But Dr. Miller is a real aerospace enthusiast. He loved airplanes, and I could see it. He pretty much talked me into staying in the program."

Scott Miller, WSU professor of aerospace engineering, modestly shies away from taking credit for Stinemetze's renewed dedication to school, but recalls his efforts to steer him down the right path: "What stood out most about Matt was that he was hungry. He wanted to do something, and there were a lot of things he enjoyed doing, like making things."

Miller capitalized on Stinemetze's love of craft by stressing that an education in engineering would give him the know-how to improve his designs and production techniques.

"He could make anything with his hands — the guy's phenomenal," Miller says. "He enjoyed building model airplanes, guitars; he was obviously nuts about airplanes. He had a tremendous amount of motivation and interest. I told him, 'Do something you think you're going to have fun at.' For him, it was 'I love building things.' And this is the same thing as engineering."

Another inspirational figure for Stinemetze came in the form of Ed Hooper, a longtime engineer at Raytheon in Wichita. The two became friendly through their mutual passion for aviation and spent time together in Hooper's garage building an airplane.

Their friendship eventually brought Stinemetze to the attention of Scaled Composites, through Hooper's association with company chief Burt Rutan.

While at WSU, Stinemetze studied, worked in the composites lab and continued laboring away at personal projects, including a full-size catamaran he and Bowman built from composite materials. In 1998, as graduation neared, the couple planned their wedding for the following fall.

Adding to the swirl of demanding activities, Stinemetze joined a team of students entering NASA's Advanced General Aviation Transport Experiments competition. The purpose of the AGATE contest is to develop ideas toward improving general aviation.

Stinemetze worked on a project called Aladdin — a drone aircraft flown from a ground station. A camera on the drone's nose broadcast live images back to the remote cockpit, where a big-screen digital avionics display provided pertinent information to the remote pilot.

The computer-enhanced display screen is not dissimilar to the "heads-up" displays found in fighter jets. This variation, designed for non-military applications, is known as Highway in the Sky (HITS). WSU's team was joined on the project by teams from three other Kansas state universities, each assigned a specific task.

"WSU built the plane," Stinemetze says. "KU designed the aerodynamics. Pittsburg State did the mission termination system, and K-State built the ground station."

Building Aladdin was stressful. "We bit off a lot more than we could chew," Stinemetze chuckles. "I think NASA got a lot of bang for the buck, because people were actually building the hardware, not just doing it on paper." In past AGATE competitions, teams were required only to produce designs, not finished, working projects.

"It's hard to work the bugs out of avionics," Stinemetze relates. "We put in a boatload of hours. It was a good learning experience, learning the real world — although we didn't want to believe it at the time."

The busy summer of 1998 included Stinemetze's introduction to Scaled Composites. He interviewed with the company, and once he had his foot in the door, he had to decide whether to stay or go.

"Kit was doing well in Wichita," he says, explaining his predicament. But ultimately, "I moved to California while she finished her master's." Not long after, he was joined by the new Mrs. Stinemetze, who took a position working with Ed Hooper at Toyota.

The Japanese auto manufacturer is developing a small general aviation plane under Hooper's experienced eye; the project, and Kit herself, have both since been moved to — coincidentally — Scaled Composites.

to its takeoff altitude.

Currently, the company has the global media buzzing with the high-flying success of its most famous project, SpaceShipOne.

The rocket-powered space plane made the first private manned flight into space in June, and on Oct. 4 opened a new era in civilian space travel by winning the coveted Ansari X Prize.

The $10 million X Prize, established in 1996 as a spur to the development of space tourism, was to be awarded to the first team to produce a vehicle capable of carrying at least three adults to an altitude of 100 kilometers twice within a 14-day period.

The prize was inspired by the $25,000 Orteig Prize, awarded in 1927 to Charles Lindbergh upon completion of his historic transatlantic flight. "When I first came to Scaled, I heard mumbles about it," says Stinemetze of SS1. "I knew Burt [Rutan] was working on it. Fairly early on, we were throwing foam models off the airport control tower — different shapes, trying to figure out which flew best."

Though SS1 remained a secret outside the company, Miller caught an inkling of what kind of project his former student was involved with. "I got a plastic model of the X-15 from him," Miller explains. (The X-15 is the U.S. government's rocket plane of the 1960s.) "He hadn't been able to tell me what he was working on, and it was interesting that he sent me the X-15. It's one of my favorite planes, and in retrospect, when he sent it, he was maybe trying to tell me what he was working on."

At that time, Stinemetze was straddling duties as project engineer on two planes: the Toyota TAA1 project that had migrated to Scaled Composites, and the White Knight, the turbojet aircraft designed to lift SS1 to an altitude at which its own rockets can take over.

of space in “feather” config-

uration, wings rotated to

slow the craft.

Stinemetze found that the title "project engineer" includes oversight of all manner of minutiae. "You're the guy who gets everything done, makes sure personnel is allocated, all the boxes are checked," he says. "Usually the project engineer has the run of the show. All the widgets, toolings, everything."

On June 21, Stinemetze's fervent study and hard work paid a great reward in personal satisfaction as the graceful White Knight soared over the Mojave Desert and into the history books.

The SS1 craft left the atmosphere, then glided safely back to earth, setting the stage for the prizewinning pair of launches in September and October.

Nothing could please Stinemetze more than helping usher in a more democratic age of aviation. "Aviation in general is really hard for the average joe to be involved in," he notes. "To certify even a stupid little airplane costs tons and tons of money. It should be easier and cheaper for people to do."

Now that the major work on the White Knight and SS1 are behind him, he's looking forward to whatever comes next. "Maybe some vacation," he laughs. "I went from the Toyota plane for a year and a half to this for a year and a half. I've done a lot of big projects. SS1 has been the longest-running program since I've been here. The next project could be big or small — I'll just have to wait and see."

Asked if he has any advice for today's crop of college students, he pauses a moment. "Stick to it," he says. "I was discouraged for a while. But if you take some risks in life, think long-term toward the payoffs, stick to it and work hard, you'll make it."

The sentiment is echoed by his father: "The moral is: If you think you might enjoy something, try it. If Matt didn't like it, he'd quit and do something else, but if he did — then Katy bar the door!"