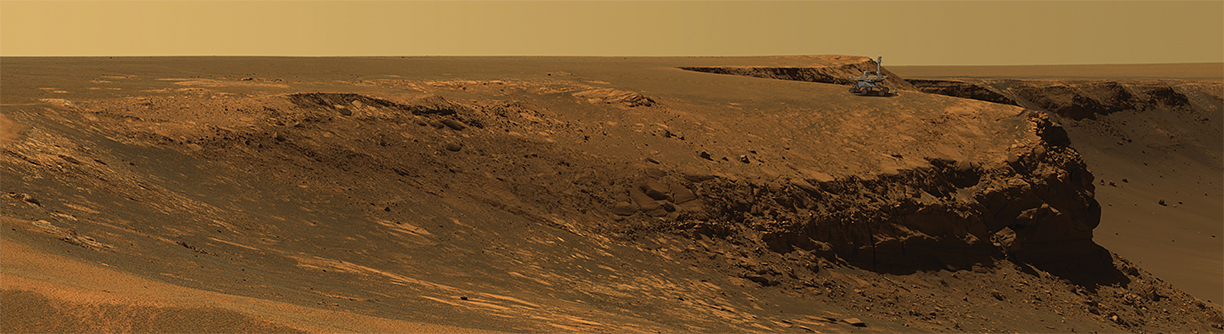

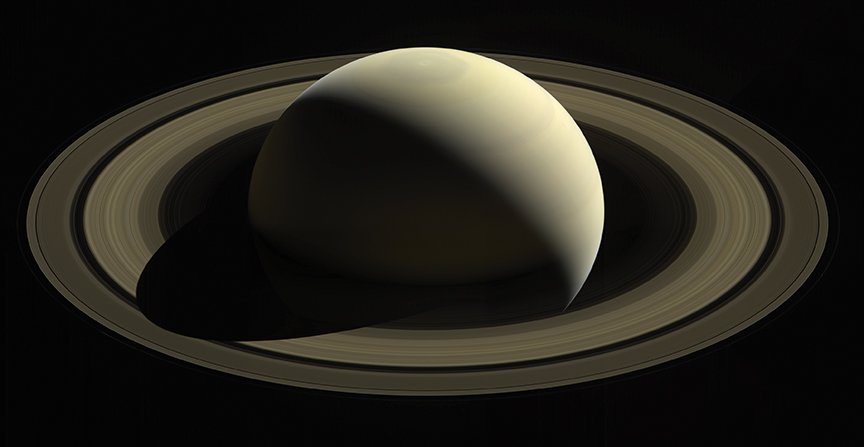

Cassini scrutinized Saturn, its 62 moons and seven tiers of rings. Opportunity roved over 28 miles of unexplored terrain on Mars. Michael Staab held commanding views of their discoveries – and their deaths.

The spacecraft Cassini died in a fiery, calculated plunge into Saturn’s atmosphere on Sept. 15, 2017. Opportunity, the Mars rover affectionately nicknamed Oppy, was pronounced dead on Feb. 13, 2019, more than eight months after the solar-powered robot rover went silent during a raging dust storm on the Red Planet – and a day after the final calls from Earth to wake Oppy up went unanswered.

Michael Staab ’13 – who earned a bachelor’s degree in aerospace engineering at Wichita State and completed a master’s degree from Georgia Tech in 2015 after working as a flight test engineering intern at NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center at Edwards Air Force Base in California and then as a test requirements and analysis engineer for Boeing in St. Louis – landed his first position at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California three years ago now. He was hired to be a Cassini flight controller for the Cassini-Huygens mission, a joint endeavor of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency – the first mission to orbit Saturn and explore its environs in detail.

Staab was nine years old when Cassini launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida, on Oct. 15, 1997. By the time the spacecraft entered orbit around Saturn on June 30, 2004, after flybys of Venus, Earth and Jupiter, the Wichita native had just finished his first year in high school, already determined to pursue a future career in space exploration. He wanted to be an astronaut. The next year, the Cassini-Huygens mission delivered the European Huygens atmospheric entry probe to Saturn’s moon Titan, where it made the first descent and landing on an outer solar system world. Titan was also a focus of scrutiny for the Cassini orbiter, which made 127 close flybys of the moon – watching its climate cycle play out over the years and studying its complex prebiotic chemicals that form in the atmosphere and rain to the surface. Cassini’s attention was also caught by another of Saturn’s moons, Enceladus, where icy plumes of spray shoot from its surface. After Cassini’s 23 flybys of the moon and a decade of study, mission scientists concluded that Enceladus hosts a global liquid water ocean, with salts and simple organic molecules.

“I came on near the end of the mission,” Staab says. “I spent almost two years flying Cassini around Saturn before I sent the last command and the spacecraft went into Saturn. The main reason we did that was to protect the two moons in particular that we believe, biologically, have got the ingredients for life to exist.”

Jump in the Fire

Since January 2016 when he became one of three people whose commands were authorized to control Cassini, Staab logged more than 1,200 hours at the Cassini flight console. He directed Cassini around Saturn scores of times, guiding it through the planet’s seven tiers of rings and by its many moons. And he was the one who commanded its death dive into Saturn’s atmosphere.

Since January 2016 when he became one of three people whose commands were authorized to control Cassini, Staab logged more than 1,200 hours at the Cassini flight console. He directed Cassini around Saturn scores of times, guiding it through the planet’s seven tiers of rings and by its many moons. And he was the one who commanded its death dive into Saturn’s atmosphere.

The decision to destroy Cassini, which had had its four-year prime mission extended twice, was made for two reasons, Staab explains. The first was that the spacecraft was almost out of fuel. Even though Cassini’s design featured nonconventional propulsion techniques that used Titan’s gravity to navigate the spacecraft around the Saturn system, fuel was still needed for the fine maneuvering of Cassini’s intricate flight patterns.

More importantly, though, the goal was to ensure Saturn’s moons would remain pristine for future exploration. “We didn’t want to touch Enceladus with Cassini,” Staab says. “Enceladus has a global, subsurface ocean underneath its icy crust, and it’s shooting samples of that ocean into space from a set of geysers at its south pole – giving Cassini samples during flybys through its plumes. Cassini detected the presence of carbon dioxide, simple organic compounds and molecular hydrogen. Not only do we have organic chemistry taking place, but there’s evidence of hydrothermal vents on Enceladus’ ocean floor. All the basic ingredients for life – water, organic chemistry and an energy source – they’re all there. And Titan’s the same way. It has prebiotic chemistry going on in its atmosphere, it has liquid methane seas on its surface, and it has a subsurface ocean, as well. So, two worlds, potentially habitable, that we didn’t want to biologically contaminate with any Earth organisms that might possibly have survived on Cassini.”

To its very end, Cassini was intent on adding to its vast collection of data about the Saturn system – about the giant planet itself, its magnetosphere, its weather and rings and moons.

Enter Sandman

After Cassini, Staab turned his astronomical gaze from Saturn to Mars, becoming a spacecraft systems engineer and flight director for the Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity, a mission that was operating well beyond its original design life.

One of two Mars twin robot rovers, Opportunity and Spirit, Oppy landed on the Red Planet at Meridiani Planum on Jan. 24, 2004. Both rovers lived well beyond their planned 90-day missions, with Oppy working nearly 15 years on Mars and breaking the extraterrestrial driving record by putting the most miles on the odometer: 28.06. In its travels, the rover found evidence that Mars had been awash in water during its ancient past and that conditions could have sustained microbial life, if any existed.

Oppy’s last communication with Earth was received June 10, 2018, as a planet-wide dust storm smothered the solar-powered rover’s location on Mars. Staab and other engineers at JPL spent months trying to wake Oppy up, to compel the Martian explorer to contact Earth. “I was the flight director on shift the week the dust storm hit and we lost contact,” Stabb relates. “And since then I’ve been the lead engineer for the recovery efforts. Part of what we’ve been doing since then is we listen every day with the DSN, which stands for the Deep Space Network and is an array of radio antennas owned and operated by NASA that we use to communicate with spacecraft in deep space. We’re also actively commanding every day – trying to force the rover to talk to us, not to send data, but to just basically beep at us.” Oppy didn’t beep back, and NASA made the decision to end the mission in February. “We did everything we could,” says Staab, who slept for weeks with his cell phone within reach, waiting for a signal from Mars.

Astronomy

Much earlier in his life, at the age of 9, Staab did get a signal from Mars. It was JPL’s Mars Pathfinder landing on July 4, 1997, which he watched on TV at his grandparents’ house, that solidified his interest in space. “It was captivating,” he says. “No one had ever seen this before, this region of Mars. I wanted to build spacecraft that fly to other planets.”

Staab’s interest was heightened, broadened might be a better word, when the STS-95 Space Shuttle mission launched from Kennedy Space Center on Oct. 29, 1998. The mission is famous for being former Project Mercury astronaut John Glenn’s return to space. “We watched the launch at school,” Staab says. “I loved it. I was like, wow, people actually get paid to do this for a living.” He remembers going home and telling his parents, already well aware and supportive of his desire to learn how to build spacecraft, “I want to be an astronaut, too.”

No surprise here: Staab has applied to NASA’s astronaut program.

My World

Staab’s adventurous nature is well suited to his professional life at NASA. But the long hours of stressful, analytical work – compounded with the pressures of putting together a JPL proposal for a data-relay network for spacecraft to replace an aging system and finishing up his doctorate at USC – demand intense methods of release and relaxation.

Staab’s adventurous nature is well suited to his professional life at NASA. But the long hours of stressful, analytical work – compounded with the pressures of putting together a JPL proposal for a data-relay network for spacecraft to replace an aging system and finishing up his doctorate at USC – demand intense methods of release and relaxation.

A cello player when he was younger, Staab says he likes to relax during the day at work by listening to classical music. A pilot and an experienced scuba diver, he spends as much of his down time away from work either in the air or underwater. Favorite diving spots are the Florida Keys and Hawaii. For quiet nights at home, he occasionally gets to settle in to read science fiction or historical fiction or to re-read something from the Harry Potter series. For something more actively creative, he likes to write music and play his guitar. His go-to genre of music is, well, this may be a surprise. “I’m kind of a metalhead,” he says. “It’s like, rocket scientist, metalhead. That’s me. When I’ve had a bad day, I just want to come home and jam heavy metal riffs.” This explains, by the way, the subheads in this story; they’re Metallica songs.

“I really love music,” he adds, “I took some music classes when I was at Wichita State. But, for me, music is a hobby. Engineering is a career.”

The View

Scoping out the view ahead of him, Staab mentions two NASA missions that have especially piqued his curiosity. One is Mars 2020, a rover project with a planned launch for July 17, 2020, and a Feb. 18, 2021, touch-down in Jezero crater. The second is both farther and further out. The Europa Clipper mission, with a launch date of TBA and a status of “future,” will put a spacecraft in orbit around Jupiter in order to conduct detailed reconnaissance of Jupiter’s moon Europa, a world – like Enceladus – that shows strong evidence for an ocean of liquid water beneath its icy crust. “It’s always exciting,” Staab says about his work. “There’s always something new out there.”

Wherever he and his spacecraft may roam.