The tribal peoples known as the Asmat are influenced, simultaneously, by three interwoven yet distinctly different realms: the spirit world of their recently dead, the sacred world of their omnipresent ancestors and their real, physical world of people, trees, water and mud. These former headhunters and cannibals spend a good portion of their day-to-day efforts on sustaining harmony among those three worlds. Yet, as WSU’s Jerry Martin discovered during his field-collecting expedition last summer, it is a bizarre concept of harmony that the Asmat strive to maintain.

The New Guinea homeland of the Asmat is the antithesis of the plains — except for the flatness. Their material world is essentially a huge, muddy flood plain covered by a forever-green tropical rain forest, strewn with fallen trees and dead sago palm leaves, and crisscrossed by countless rivers and streams that, where they empty into the vast Pacific, seem to breathe with the rhythm of the often treacherous ocean tides.

Nearly inaccessible from the sea on one side, protected on the other by snow-capped mountains, the secluded land of the Asmat lies in the southern quadrant of the western half of New Guinea, in Indonesia’s Province of Papua, formerly called Irian Jaya. The remoteness of the region paired with the Asmat’s own fierce reputation as headhunters and cannibals kept the outside world at bay for centuries. The explorer James Cook met hostile Asmat warriors while attempting to land in 1773, but it wasn’t until the late 19th century that the Netherlands became the first foreign power to gain political hegemony over western New Guinea. During World War II, Japanese forces occupied the land, which was returned to Dutch control in 1945 and, after military engagements between Indonesia and the Netherlands, passed via a United Nations-sponsored plebiscite into Indonesia’s political sway in 1969.

“The first Catholic missionaries came in 1953,” says Jerry Martin, the director of Wichita State’s Lowell D. Holmes Museum of Anthropology, “and their accounts are fascinating. They talk of headhunting retribution raids, and they give examples of the strange — to us — sense of justice and harmony that the Asmat have.” Although the last confirmed headhunting incidents occurred in the 1970s, the symbolism of Asmat culture is still rife with ideas and images related to the practice. The concepts lying behind it cannot be easily understood. Yet its deepest function, Martin says, was restoring harmony, or a balance of power, to their world — an overarching purpose that ties in fundamentally with their basic view of things.

For the Asmat, recently deceased persons and those already in the realm of the ancestors are seen as vital, active aspects of the circle of life. The return of the dead to earth through reincarnation is an ongoing natural process, and in the past the ritual bestowal of a headhunting victim’s name to, for example, the killer’s young son ensured the victim’s continued existence. Since the victim’s spirit and name lived on in the child’s body, the child was then welcome in the hostile village. “That’s why the names of enemies had to be known before they could be killed,” Martin says. “This is certainly bizarre, but I think we can see a certain underlying harmony here.”

It was into this fascinating, yet alien world that Martin journeyed last summer. At expedition’s end, he transported to Wichita State nearly 950 items collected in the field that now comprise one of the nation’s premier collections of Asmat tribal art. Funded by Barry and Paula Downing, who themselves have explored the world of the Asmat, the field-collecting expedition lasted nearly two months, cost “in the six figures,” as Martin puts it, and was fraught, from start to finish, with one spirited adventure after the other.

PEOPLE OF THE TREE

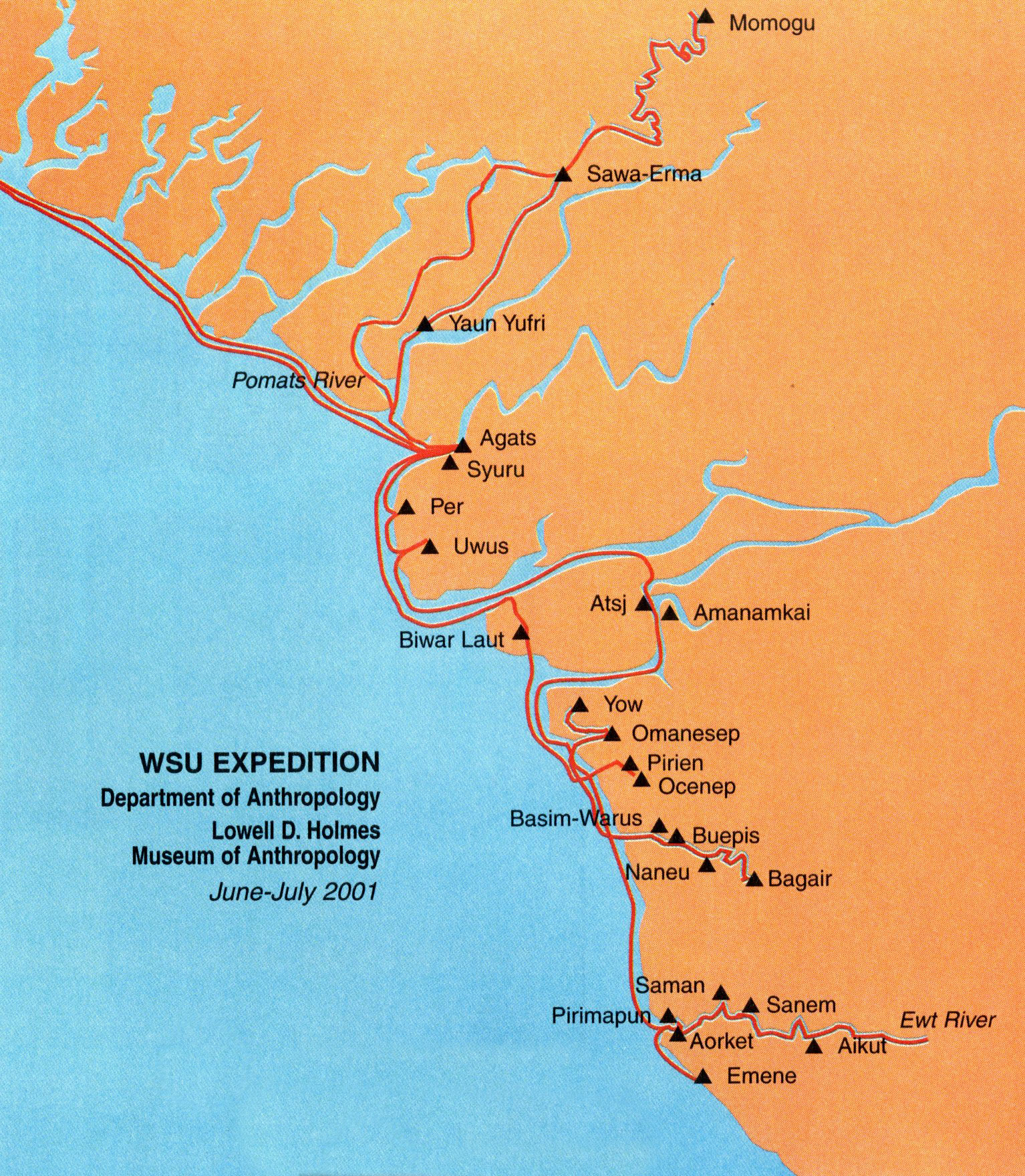

New Guinea, the world’s second largest island, rises out of the Pacific Ocean just below the equator. Martin flew into the coastal town of Timika, where he and Patti Seery, a cultural expert who handled trip logistics, hired a boat and crew to take them to the town of Agats, where they would set up their base camp.

New Guinea, the world’s second largest island, rises out of the Pacific Ocean just below the equator. Martin flew into the coastal town of Timika, where he and Patti Seery, a cultural expert who handled trip logistics, hired a boat and crew to take them to the town of Agats, where they would set up their base camp.

The journey should have taken about 10 hours, but the seas were rough and the trip took two days. They spent the first night out sleeping on the beach, spectacular lowland rain forest reaching back from the sea into the island’s mysterious interior. Where sea and fresh water mix along the coast, the habitat of the mangrove swamp emerges, and in shallow freshwater swampy areas the sago palm flourishes. Both the mangrove and the sago figure prominently in the lives and the art of the Asmat. In fact, Asmat means “people of the tree.”

“We arrived in Agats on the 5th of June,” Martin says. “Agats, which is all on stilts, is a government center. There are churches, a hospital and a little bank. We heard, but I wasn’t able to actually confirm this, that the vault in the bank is a refrigerator.”

Martin and Seery met up with Yefen Baykal, a former director of the Asmat Museum in Agats. Now serving as director of an economic development organization that seeks to guide the Province of Papua toward a more autonomous existence, Baykal had agreed to have his house serve as expedition headquarters. From there, Martin and Seery hired a crew and made final preparations for their first field-collecting excursion.

“Our group fluctuated from eight to 10 or so people,” Martin says. “Besides Patti and me, we had an English interpreter, Ronny Fordatkosu; Bokway, a policeman who served as our speedboat driver and acted as bodyguard; interpreters for the northwest and southeast regions; and four boatmen. We had three boats: two longboats, each roughly 3-feet-wide and 40-feet-long, and a speedboat with a 75-horsepower motor.”

COMMUNITY CENTRAL

From Agats they set out for the twin villages of Sawa and Erma — heading out to sea and along the coastline, then up the Pomats River. Asmat villages are located on riverbanks and vary in population from around 1,500 to 50. Sawa and Erma run together to form one village of perhaps 800. Like all Asmat villages, Sawa-Erma is divided into sectors, each sector centered around a ceremonial house called a yeu. Each family, or hearth group, has a fireplace in the yeu, but women traditionally are not permitted inside except on special occasions. As the ceremonial center of the community, the yeu is the foremost place where rites are performed, feasts are celebrated and, from time to time, foreign visitors are welcomed.

“We followed a standard pattern when greeting villagers,” Martin explains. “We would find the ceremonial house and wait until we were invited in. Then we presented leaf tobacco and explained our purpose, that we were from a university museum and had come to learn about their culture so we could teach people about the Asmat. We explained we wanted to buy ceremonial and everyday items.” He pauses and adds, “While collecting, we had to be extraordinarily careful not to cause disharmony between individuals, between villages, between spirits and individuals, between spirits and spirits. Suffice it to say, it’s complicated.”

June 8 was the expedition’s first major buying day. Although few shields or drums were found, the women of Sawa-Erma excelled in the women’s art of weaving. In addition to making floor and sleeping mats, they had once again begun weaving decorative, ceremonial mats called pir. Made from sago leaves, pir are used in such ceremonies as initiation rites. Since other Asmat women no longer make the mats, they hope to build a thriving business.

The next day, expedition members watched a dugout canoe ceremony. “The ceremony invokes the spirits into the canoes,” Martin explains. “They painted the boats, then burned them to harden the wood, then scraped and repainted them before launching them and having a dance and boat race. The canoes are narrow, just about 18 or so inches wide. Demonstrating phenomenal balance, the Asmat row the canoes standing up with long oars, some of them beautifully carved.”

On June 10 the group started upriver for Momogu, but the speedboat’s motor broke down. Back in Sawa-Erma, it took a day for repairs. That evening, Fordatkosu, a musician and songwriter who, in addition to interpreting duties, recorded Asmat music during the trip, treated the children of Sawa-Erma to an impromptu concert.

They reached Momogu the following day — boating through a vast sago palm forest. “Momogu had the first dry land I’d seen in a week,” Martin remembers. “I was very happy to be walking on dirt.”

SPIRIT POLES AND SACRED SAGO

The prize finds of June 12 were two omus, or spirit poles. The sacred carvings symbolize the three partially interchangeable realms of the Asmat: the earthly world; the safan, the world of the ancestors; and a limbo inhabited by the souls of the recently deceased.

Because omus are used in village-wide ceremonies, the entire village participated in setting the price for them. When a price was settled on after much negotiation, “the people clapped and congratulated one another,” Martin recalls. “The omus were wrapped in leaves and, because of their sacred power, were taken around the village and downriver to be loaded on our boat. They weren’t allowed to be seen by women or uninitiated children.”

While the Asmat consider the canoe, with its clearly phallic shape, to be the male symbol par excellence, the sago palm tree is seen as female. Weeks before a village feast, a particularly beautiful sago tree is selected as the “mother” of the feast and ritually cut down. Holes are made in its trunk so the Capricorn beetle may easily reach the interior where it lays its eggs. The sago is left alone for six weeks, the time it takes for the larvae to mature. To the Asmat, the sago worms are not only delicacies, but also symbolize new life emerging from the female body.

Back in Sawa-Erma, Martin and his expedition mates learned they were to be offered the Asmat delicacy during a festive picnic. “That morning, they told us they came to get us for the picnic at 5 a.m., but that we didn’t wake up,” Martin says and laughs. “Later in the morning, they took us by canoe to a fairly dry spot where they had made an arbor with palm leaves, a huge arbor some 300 feet long. I ate my first sago larvae there. Cooked grubs have a smoky flavor, something like eating the cooked fat of a steak. When you eat them raw — meaning alive, which I didn’t do — you bite their heads off, or they’ll bite you first. We later saw necklaces made out of what we thought were seeds, but which turned out to be the little, dried heads of the grubs.”

After the picnic, they boated to Yaun Yufri before returning to Agats to prepare for their trip south, where they’d heard very few people had gone to collect. The plan was to set out early on June 15. But one of the regional interpreters, Donatus, was missing.

“At about two in the afternoon, we decided to head out,” Martin relates. “We left word for Donatus to meet us in Atsj, where we overnighted. Some of the little rivers are unnavigable at low tide, so we thought maybe that was the problem. But he never showed up, and we sent Bokway with the speedboat back to Agats to look for him.”

BEAUTIFUL BIS

On June 16, while waiting in Atsj for news of Bokway and the missing interpreter, Martin saw his first bis poles and purchased two of the ancestor poles on a short side-trip to the village of Amanamkai. The bis pole, he explains, may be regarded as the most characteristic and monumental example of the Asmat’s art of carving. Traditionally made from the trunk and prominent plant root of a mangrove, bis poles — with their intricately carved figures of humans, animals, plants and inanimate objects such as drums and sago bowls — stand an imposing 15- to 24-feet tall. Every bis pole was tagged with all the background information it was possible to gather. “We wanted to know things like the owner’s name, who made it, its function, an interpretation of its design and what spirit lived in it or was associated with it,” Martin says, stressing that it is the provenance, or history, of every Asmat item that infuses WSU’s collection with true research value.

Bokway arrived in Atsj June 17 with word that Donatus had gone on to Pirimapun. Later in the day, Donatus himself arrived, and the reunited group set off for Pirimapun and Aorket. As they neared the two villages, a traditional greeting party welcomed them. “The villagers came out in ceremonial regalia,” Martin says. “They sang and danced, and when we landed the boat, they picked Patti, Ronny and me up and carried us to the terrace of the men’s house.” And in the morning, the villagers presented them with a bill for $900. “Patti explained we wouldn’t pay for ceremonies,” Martin says. “It was a matter of principal. The bill seemed to have originated from non-Asmat local officials, and the older Asmat men agreed with Patti that they should not sell their culture.” After lunch, they traveled to Emene, where the villagers had already heard about the welcome and the bill. They feted the expedition members with another welcoming ceremony — no charge.

Back in Pirimapun-Aorket, while making purchasing arrangements in the yeu house, Martin noticed that Donatus seemed unhappy. “I learned his grandfather was killed and eaten in that yeu. He stayed outside. There were too many bad spirits for him.”

A trek up the Ewt River was planned for June 19, but Martin and Seery had their hands full convincing the crew to go. They had not been in the region before and were hesitant about entering an unknown area. Once convinced, they trekked upriver, passing the villages of Saman, Sanem and Aikut and then out of Asmat territory. “We crossed into a non-Catholic mission area,” Martin explains. “The landscape changed, with the jungle becoming less dense. The boats and villages looked different. There were no men’s houses. We stopped at one village, where they told us they didn’t have any culture left. One old man asked if we wanted to see the village’s most sacred treasure. We were excited and honored to accept and watched as he slowly unwrapped an object wrapped in leaves. It was an electrical, white porcelain conductor. That was very sad. We rapidly went back to Asmat territory.”

They overnighted in Aikut and the next morning purchased two drums with patina on them, which dated them to pre-World War II. Their next stop was at Saman, where the villagers were expecting them. “They even had a table with a pencil and guest book for us to sign,” Martin relates. It was then on to Basim-Warus, where they had heard a mask ceremony was to be held.

SOUL MASKS AND A CASSOWARY

The idea behind the mask ceremony, Martin explains, is to reestablish harmony through a ritual release of souls stuck in limbo. Seven men had woven elaborate body masks for the ceremony, which was being overseen by two older men. Because the rite had not been performed for more than 17 years, young boys who were traditionally not allowed to see the mask weaving were invited to watch. “They were very attentive, very serious about learning,” Martin relates. “After the villagers danced and sang all night, the masks were presented the next morning. The villagers had to show the mask spirits that everything was fine, that it was safe for them to move on to safan. To the sound of a very somber drum beat, the seven mask spirits led the villagers on a tour of the village.”

That afternoon, expedition members wended their way to Naneu, Buepis and back to Basim-Warus, where they bought shields and concluded arrangements to buy the seven masks. By June 24, they were beginning to run out of supplies, but traveled to Buepis to see more bis poles and then to Bagair and on to Omanesep, where a shield ceremony had been held a short time before. After making arrangements for supplies and also for the transport of their many purchases back to Agats, they visited Yow, where they found the most beautiful bis poles they were to see on the trip. On their way back to Omanecep, Martin with struck by the sight of thousands of white birds flying out of the lush green of the jungle. “There were cockatoos and other birds,” Martin recalls. “We stopped the boat. The sound was ear-piercing.”

From Omanecep, they boated to Ocenep, a village near where it is believed Michael Rockefeller drowned during his 1961 Asmat expedition. “We went up a beautiful, small river where you could almost reach out and touch the jungle on both sides,” Martin remembers. Their next stop was Pirien, and just at sunset they arrived at the large village of Biwar Laut. “A cassowary was sitting on the dock,” Martin says. “We found out that one day the bird had simply gotten into one of the villager’s canoes. It lived in their village and would only eat food out of their hands. They saw it as a reincarnated ancestor.”

The group returned to Agats, where they spent the bulk of the next two weeks catching up on paperwork, making shipping arrangements and packing items in rice bags. They also made a few side-trips, one next door to Syuru and another down to Uwus. The trip to Uwus was ill-fated. “Ronny had this uncanny ability to feel when something would go wrong. When he felt like this, he wouldn’t take his guitar. He didn’t take his guitar when we left for Uwus,” Martin relates. “A trip that should have taken half an hour took considerably longer because the back of our boat broke and the motor fell into the sea. The sea was shallow, so we recovered the motor and limped into the nearest village, Per.”

Since, to the Asmat, nothing on earth happens naturally, but is caused by the spirits, the Asmat crew members now stopped to consider why the spirits were causing such misfortune. The next day brought high winds — and provided a rationale. The spirits weren’t angry; they had actually saved the expedition by keeping them off the sea and out of the dangerous winds. Harmony restored, the group returned to Agats.

They finally got to Uwus on July 13, as the villagers were planning a bis pole ceremony. They had just cut down some sago trees in preparation for the feast six weeks later.

Back again in Agats, Martin settled the expedition’s bills, had a party for the crew and planned to leave for Timika with a small crew comprised of Ronny, Bokway and Bokway’s brother, Bobby, when the tide was right at 3 a.m. “We finally got off about 6 a.m.,” he recalls. “About four hours out, the boat breaks down. That night, we had a little rice and chicken to eat and went to sleep in our tents. The next day, we had no food and just a little water. We were in a very remote place. Bokway left early to try to find his friends who had sago land nearby. By that afternoon, I was starving, and Bobby seemed depressed. I rigged up some fishing gear from a tree branch and tried to fish. Bobby thought that was the silliest, funniest thing he’d ever seen, and it snapped him out of his depression. He collected zebra snails for us to cook for dinner. Right at sundown, Bokway and his friends came, bringing sago and fish to eat.”

They left the next morning, arriving eight hours later in Timika, where, Martin shares with obvious relish, “I had my first real shower in weeks.” Back in Wichita, he learned via e-mail on July 19, four days after he’d left New Guinea, that a large area in Agats had burned to the ground. “No one was hurt,” he says, “but we would have lost the entire collection.”

The spirits must have been smiling.