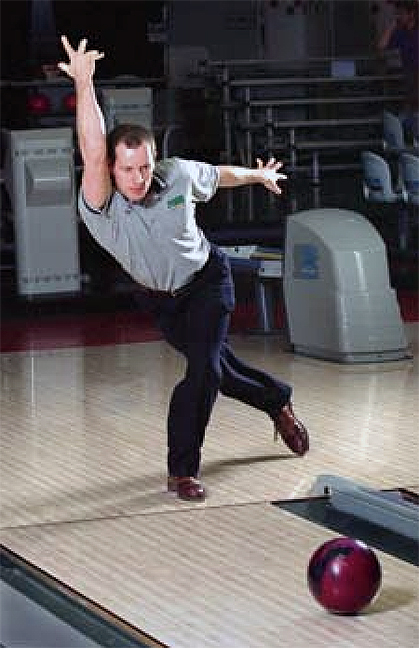

We’re all familiar with the inner rumblings of bowling centers, the thunder of rolling balls across conditioned lanes, the sound of setting pins like deus ex machina — cacophonous to some, cathartic to Lonnie Waliczek ’96.

We’re all familiar with the inner rumblings of bowling centers, the thunder of rolling balls across conditioned lanes, the sound of setting pins like deus ex machina — cacophonous to some, cathartic to Lonnie Waliczek ’96.

Lowell “Lonnie” Waliczek contends on an invisible surface. As a member of the Professional Bowlers Association, the lanes that he bowls may be visible, but the transparent oil and conditioner that govern the lanes and their usage are constantly changing and challenging his game. To be successful on the PBA requires a sublime touch and a paradoxical blend of knowing when, and when not, to think. And for someone who chose to study the classics in college and chides himself as being too analytical, the process of thought reduction sometimes becomes a problem.

“Bowling is a liberal art,” Waliczek says late one night at his Wichita home, which is filled with an assortment of bowling memorabilia he’s collected through the years. It’s one of few excursions home on an almost 30-week odyssey that is life on the bowling circuit — it’s a chance to be with his wife Amy fs ’93 and their 2-year-old daughter Olivia.

“Like any art or craft, there’s a subconscious side, and the less you can think once that tool, or that ball, is in your hand, the better off you are. But, for myself,” and this is something he says he’s been working to improve, “if I can narrow it down to one or two things, that’s a good day. Less than that is a great day.

“The conscious side is staying ahead of the lane conditions — making adjustments to that oil as it moves or breaks down on the lane.” There are ripples created by the passage of each ball, only you can’t see them. Once you understand the lane, you let the memory of your muscles take over. “That’s why you practice. So that you can recreate the shots you’ve seen yourself do thousands of times. You just see your way through it.”

Waliczek spends a significant amount of time in hotels across America. And he spends an average of about 24 hours a month on the road, driving with PBA player and roommate Jason Duran between the different cities that comprise the tour. He spends the time with his thoughts on home and bowling, seeing his way through being a better father and a better bowler.

Sometimes, he says, he’ll listen to National Public Radio or late-night call-in radio host and impresario of the weird, Art Bell, for background noise. “But let’s get this straight,” Waliczek says. “I may look around for the black helicopter or the little people, but only because it’s that late, not because I’m buying into it.”

Statements like those, his keen sense of humor and his tendency toward kindness are the reasons, his wife says, he’s gaining popularity on the circuit. “People will follow him around all week, just because he takes the time to talk to them. He’s so generous with his time and his compliments.”

“You’ll never meet anyone nicer,” says his father, Paul Waliczek. “And my wife and I have no idea where he picked that up.”

Current WSU bowling coach and legend in the bowling community, Gordon Vadakin ’82 says he surely received it from his father. He also picked up the family tendency toward bowling. Paul Waliczek bowled at Wichita State in 1968 and 1969, moving on to coach the team from 1971 to 1975. The team won its first women’s National Championship with Paul Waliczek.

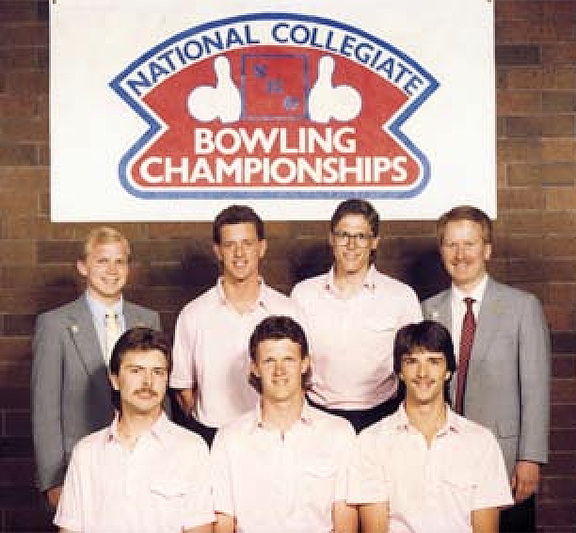

finished second at the National

Collegiate Bowling Championship,

Portland, Ore. From left, top row,

Richard Renollet, Lonnie Waliczek,

Chris Barnes, Gordon Vadakin;

bottom row, Dan Dick, Billy Murphy

and Pat Healey.

Paul Waliczek is quick to admit, though, that it’s under Vadakin that the program has really grown to greatness. Vadakin has coached in nine National Championships and, according to a 1997 issue of Sports Illustrated, runs the premier collegiate bowling program in the country. Under Vadakin’s control, Wichita State has consistently produced some of the world’s best bowlers. So it’s not unusual to have wsu graduates such as Chris Barnes ’92, Patrick Healey ’92, Rick Steelsmith ’89 and Waliczek competing for the win in a major tournament.

And it’s under Vadakin — who Waliczek refers to as “the Dean Smith of bowling” — that Waliczek and the others acquired many of the skills necessary for success in the PBA. “He taught us that confidence is 80 to 90 percent key,” Waliczek says. “You’ve seen yourself do it. You just have to remember. You see this in every sport — someone has a little success and they start thinking, they start believing that they actually belong. This snowballs. Then you can do it week in and week out.”

“It takes very intelligent people to play this game,” Vadakin says, stressing that bowling in the pba is very different from playing at your local lanes. “There’s so much more depth.” For example, the oil and conditioner are laid in a far more complex pattern. “What they bowl on is invisible. That surface changes with each bowling ball that passes over it. All that oil is moving, shifting. It’s changed by the identity of those who bowl on it. And you have to adjust to what you can’t see. It’s a game of touch and feel and instinct.”

Former WSU bowling teammate, two-time All-American and Waliczek’s cousin, Billy Murphy explains from his office at Northrock Lanes, “Players can move this oil to either help or hinder those they’re playing.” And that, he says, “is why they practice so much. No one I know practices as hard as Lonnie.”

It’s uniting the mind and everything learned in practice that makes for great athletes. “All athletes need to remember to relax,” Vadakin says. “Tension blocks the ability to make decisions. Great athletes know when to think and when to shut the mind off and let the body go. It’s muscle memory. It’s a flow state.

“We’ve had a lot of special people in this program, and Lonnie is one of them. He brought more than his bowling success. He brought his intelligence, his ability to reason through a situation, to work within a team structure and a tremendous amount of loyalty. Lonnie’s gray matter is his greatest weapon. He was everything a coach could ask for.”

Vadakin adds, “He’s on the road 20 to 30 weeks a year. There’s not a lot of glory in this, and there’s not a lot of money. But if people pursue dreams, dreams become reality.”

Looking to make those dreams true, Waliczek, who earned his bachelor’s degree in creative writing, says he spends more time on his mental game lately, trying to combine his analytical mind and his muscle memory. “If you gravitate toward literature or philosophy,” he explains, “you often come across the idea that we don’t really have control. But in sports, if you don’t think you have control, you might as well not go into it because that other guy believes — he knows — he can control the situation and the outcome, because he has more confidence. That’s where things get muddy for me sometimes. My intellectual and sport lives don’t always see eye to eye. But I’m learning to make it work. Bowling is what I do. I’ll get it done.”

Waliczek’s subtle skills and analytical mind fused in February for a second-place finish and a $50,000 check at this year’s PBA World Championship in Toledo, Ohio. And though this season is coming to a close, he’s looking forward to carrying this success and this catharsis over to a new season.