a permanent, finished object. This is especially true of his crop art,

which, despite long and meticulous planning, rarely takes shape as

envisioned, then blooms and fades — or is plowed under when the

season turns.

For 30 some years and counting, this Kansas-born artist has been using the land as both palette and canvas.

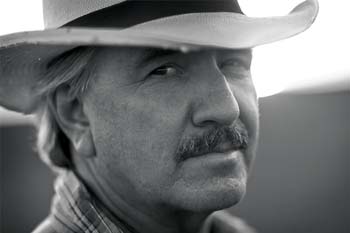

Stan Herd’s connection to the land is strong — as strong as the steel plow that first broke the sod of his native prairie more than a century ago now.

Born into a family that has farmed for three generations on the windswept high plains of southwestern Kansas not far from the small town of Protection, Herd moved to more metropolitan places, including Wichita, where he attended Wichita State, before settling in Lawrence, Kan.

From his home base, he travels often and far. As of this writing, he has just returned from Brazil, where he went to check out the art scene.

Before he left, he took the time to share a few thoughts about art, warriors, bull riders — and seeking middle ground.

For more than three decades, Herd has been using the land as both palette and canvas, creating singular images on a grand scale by plowing, discing, planting, mowing and otherwise manipulating the environment.

His earthwork art ranges in subject from the Kiowa leader Satanta and the Oklahoma-born humorist Will Rogers, to the commercial logo for Absolut Vodka and a covertly made promotion for the 2002 Mel Gibson movie “Signs.” His artworks range in style from the purely representational to his recent “Abstract,” a half-acre piece created from a patchwork of mulch, soil amendments and plantings for a national advertising campaign now airing for John Deere.

Herd, who established himself as an artist with oil and watercolor painting before returning to his agricultural roots to pioneer crop art in the late 1970s and early 1980s, acknowledges a number of things that came to his attention in the 1970s and interested him in the idea of environmental art, in art that was constructed on such a large scale that it could be appreciated fully only when viewed from above.

He remembers watching two different television documentaries, each of which made a huge impact on him. One was about the environmental artist Christo, who spent four years constructing a temporary “running fence” across the hills of California. The other was about the ancient, mysterious line drawings etched into Peru’s Nazca Desert.

“All art, thought, superstition and religion connect to the ancient,” says Herd,

who is also a noted muralist and sculptor. “We are just regurgitating that which remained in written form or was spoken through the millennia or was passed

down by legend or myth. The artist just keeps telling the same old story, with

the hope of inculcating that message in his time. Sometimes I think it is just a

fight to see whose stories the masses believe. Are you for a healthy planet? For

a basic sense of compassion for others on the planet? Or are you just a tea-party voice for Me?”

Although he won’t admit to favorites among his earthwork art, he does say that he has found the experiences gleaned from his 1994 project “Countryside,” a one-acre image of a pastoral Kansas landscape on property owned by Donald Trump on New York City’s west side, and his trips to Havana to create “Rosa Blanca,” an image of a white rose in honor of the 19th-century Cuban poet José Martí, to be “certainly more profound” than others.

“‘Countryside’ was very powerful,” he explains, “in the sense that so much was on the line plus the polemics of working with Trump’s vice presidents and homeless folks. The level of stress on myself and my family to make it happen was intense. I felt like a warrior — both the good side and the bad side — fighting for right but leaving the family to do it. War always has a selfish side for men. We go because we believe, but we leave a lot of people in our wake.” Herd’s nyc experience is the subject of Chris Ordal’s independent film “Earthwork,” with actor John Hawkes playing the younger Herd and part of the storyline covering the break-up of Herd’s marriage. For more about this film project, visit earthworkmovie.com.

Herd says his experience in Cuba stands as “the most important, the most stimulating, the most revelatory. Creating a work of art across international borders at the end of the Cold War is my greatest accomplishment times ten. The artwork itself was mediocre.”

with the wheeling of the seasons and

rely on photography to capture a lasting

record of them, Herd has completed a

number of more permanent pieces.

Although most of his earthworks fade with the wheeling of the seasons and rely on photography to capture a lasting record of them, Herd has completed a number of more permanent pieces. To name three: “Prairie Henge,” a half-acre homage to the Osage Nation and the tallgrass prairie; “Portrait of Amelia Earhart,” commissioned by Earhart’s hometown of Atchison; and “Medicine Wheel”, a collaborative effort with members of the Haskell Indian Nations University. All three are located in Kansas.

It took Herd nearly five years to finish his first earthwork composition, his portrait of Satanta (1981). It was a “subtraction” piece, a wheat field left in stubble with the lines of the image plowed into the darker soil. “I dreamed about and planned it for four years before I actually went to the field,” he recalls. His “Little Girl in the Wind” (1988), a portrait of Carole Cadue of the Kickapoo tribe, was a collaboration with environmental activist Wes Jackson and the Land Institute in Salina, Kan. “Little Girl” was Herd’s first prairie piece to be created without plowing.

Crop art, he discovered years ago now, is an expensive undertaking, plowing or not. Leery at first about taking on purely commercial projects, he has since sought equilibrium in the pull between art and art as the product of commerce. He accepts — and excels at — commercial/corporate art, yet does so in order to have the financial freedom to create on his own terms, too. In his 1994 book, Crop Art and Other Earthworks, he writes, “I do still believe the modern artist has a responsibility to maintain a position of objectivity outside the system of commerce. The catch-22 is that the hungry artist looking for a way to survive often finds it necessary to pursue the marketplace of the art world, the marketplace of the corporate world or government grants.”

In so many aspects of his art and life, Herd continues the search for balance, for a workable equilibrium — for that middle ground — between the demands of art and family, art and commerce, city and country, transience and permanence.

Thinking back to what motivated him to take up his earthwork ventures, he says, “I like to think that I set myself up in a mindset that considered the possibility of innovation. The creative process is about stealing and re-creating that which came before — making it your own in a way. True innovation is so rare in music, poetry, writing and art that we are left to study the masters and hope for inspiration, for a stone untouched.”

Herd has achieved worldwide notice. His art has been featured in numerous publications, including National Geographic, the Smithsonian, the Wall Street Journal and People magazine. He has garnered many awards, including being named Kansan of the Year in 1996. So how

does Herd, who as a boy spent untold hours alone on the tractor

watching red-tail hawks dive for field mice, take to this high-profile acclaim?

“I told a young musician friend the other day that creating art — music, poetry, film — is akin to a religion, a belief that you are here for a

purpose and that those who figure that out live life at a level that is not available to others,” the artist says. “That is your gift. You can’t fail, if you don’t quit. The rewards, the trophies and the applause are secondary. Even the bull rider, the true cowboy, doesn’t ride for the trophy. He rides for the thrill of the ride. It is something that those fearful of getting on never experience — same with making art.”

Ride on, Stan Herd, ride on.