For 40 years, Wichita State has been a vital part of Kansas’ system of higher education. But it took a war.

And it took the uncommon skills and supreme commitment of two highly respected scholars and gentlemen — the University of Wichita’s last president, Harry F. Corbin ’40 (1917-90), and WSU’s first, Emory K. Lindquist (1908-92) — to seal the deal.

Corbin led the battle to bring WU into the state system, against all the odds and against some of the most powerful political figures in Kansas. He proved himself to be not only a charming, urbane administrator, but one of the most skillful tacticians and political infighters Kansas had ever seen.

Lindquist, sustained by his belief in the “life of the mind” and surely the only professor ever knighted for contributions to Kansas education by the king of Sweden, guided WSU through an exciting, but often exhausting, transition from municipal to state university.

THE SOLDIER

By Cynthia Mines ’82

In 1984, as editor of WSU alumni publications, I set out to write an article to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the university’s entering the state system.

I scheduled interviews with many who had been instrumental in the decade-long effort. One clear theme emerged: It likely wouldn’t have happened without the strategic leadership of Harry Corbin, then president of the municipal university.

I called Dr. Corbin, who still taught religion and political science classes at Wichita State. He politely declined to talk with me.

I panicked at the thought of my cover article disintegrating. I gently persisted, and he explained it was best for the university if he stayed out of the public light, that all the wounds he felt he had created had not yet healed. I asked if he’d speak with me if I didn’t quote him. He agreed and explained how to find his office in Jardine Hall.

It turned out his office was behind a nameless door I’d passed many times on Jardine’s first floor. Inside the book-lined room sat a tall, reserved gentleman who wore his scholarly demeanor graciously. He was reticent to discuss specifics of the often-bitter battle and even more reluctant to accept credit for the move that had transformed the university and the city of Wichita.

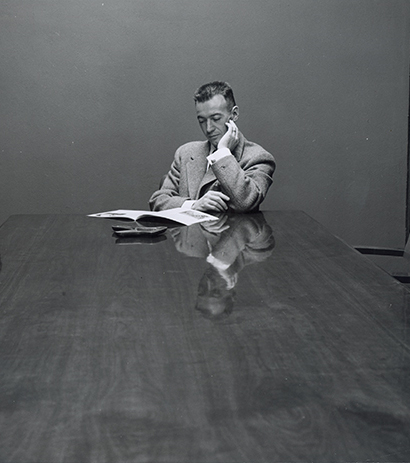

I used Ablah Library’s Special Collections to fill in gaps. Dr. Corbin had declined to be photographed, but I found a photo of the handsome president in the archives. When he had taken the mantle of the presidency in 1949 at the age of 32, he was the youngest college president in the nation.

After the alumni magazine was published, he called to compliment me on the article. After that he sent me occasional notes, but we lost touch after I left campus in 1986. Three years later, I got an unexpected phone call from him. He asked if I’d meet him at his office, which was now in the Liberal Arts and Sciences building.

He was as I had remembered him, but his office quarters were more cramped, filled to bursting with filing cabinets, boxes and shelves of books. We chatted a bit, then he broached the subject of the visit: He needed help sorting through all the files.

I was pleased he trusted me with such a task, though it appeared daunting. He conceded some of the papers from his years as president probably should be sent to special collections but that the files from his teaching years could just be thrown away.

He gave me a key to the office and said not to worry about disturbing him, that he likely wouldn’t be there. A few months later, I received a handwritten letter explaining what I had suspected: He was ill and expected not to live much longer.

A picture of Winston Churchill he’d propped on a file cabinet watched over me as I worked. His office was filled with books reflecting his broad interests, ranging from Emily Dickinson to FDR’s bound letters to Zen. The greatest collection, in size, was the part of his library devoted to Islam.

As I sorted files and skimmed their contents, my already great respect for this man grew. His speeches, which he wrote himself, were filled with vision and hope and his vast knowledge of poets and philosophers. I found files full of speeches he delivered to faculty groups, Rotarians, Campfire Girls, nurses, accountants.

During a 10-day period one May, he traveled to half a dozen high schools to deliver commencement speeches — and one graduating class had only four seniors. Each speech was unique, with a well-thought-out and supported theme.

In a desk drawer, I found a travel diary that told of visiting India, where he took off his shoes and literally walked in Gandhi’s footsteps.

A copy of his résumé showed his graduation from WU in 1940; a bachelor of divinity degree from the University of Chicago; service as a chaplain during World War II; a year at Stanford University law school; a law degree from the University of Kansas; and a doctorate from the University of Chicago.

It made brief mention of having to withdraw as WU’s Rhodes Scholar candidate in 1937 but didn’t mention the reason: the death of his father and leaving school for a few years to tend to the family’s business. In 1946 he joined the WU faculty as assistant professor of political science and philosophy.

A yellowed newspaper clipping said that when WU went looking for a new president in 1949, someone at the University of Chicago told members of the search committee to look no further than their own school, that the best man for the job was already there. The WU regents, however, approved his hiring by only a one-vote margin.

I discovered that he’d visited every single county and every legislator during the years WU fought to be accepted into the state system. I found a rubber-banded stack of oversized index cards on which he’d pasted a photo of each legislator and written notes.

The effort to gain state aid began in 1955, but attempts in 1957 and 1959 failed. The most startling discovery of all was a letter President Corbin had written in 1959 — four years before WU was admitted to the state system — informing the chairman of the WU board of regents that after a decade as president he had “grown weary” and wanted to return to teaching.

One can only wonder what the university would be like if he’d been allowed to resign then. The first semester as a state school in 1964, tuition dropped by 35 percent and enrollment jumped by nearly 50 percent.

His files held copies of the various Senate bills introduced to create a state university in south-central Kansas as well as hundreds of letters and speeches given as part of the effort, demographic studies, charts of student numbers in each grade and population projections for central Kansas.

There was a copy of the infamous Eurich Report, which had infuriated Wichitans with its recommendation that WU be placed under the auspices of KU and K-State.

An outside study in 1960 brought renewed hope to the effort, but editorials across the state lambasted the idea, with a lengthy Salina Journal editorial stating that making WU a state university would be the “biggest white elephant ever given in Kansas.”

Though the state effort was all-consuming, Dr. Corbin didn’t neglect the everyday workings of the university. His high regard for academic freedom was evident in the many letters he wrote upholding the rights of professors and campus speakers to discuss controversial topics.

During the McCarthy era, he wrote many letters fending off Communist allegations and expressing concern about Wichita’s ultra-conservative and controversial John Birch Society.

Many files held carbon copies of recommendation letters, each a unique effort, for students and faculty. Others held letters of encouragement, congratulations or condolence. A few mentioned loans to help worthy students pay tuition.

One held correspondence with attorneys and judges about an international student charged with a felony. In them, Corbin expressed his support for the Muslim student and offered to become a “surrogate parent.”

Critics of the state effort said that even if the legislature approved WU’s admission, Wichitans would not support transferring the municipal university to the state. But Wichitans overwhelmingly approved the plan — by a vote of 30,980 to 1,051 — in May 1963.

The very next day, in a letter dated May 15, Harry Corbin informed the regents of his intention to retire from the presidency. He asked for a year off, then a return to the classroom.

The request came as a shock to the regents and the state. I asked him if he’d always known he would resign. He said yes, no matter which way the vote had gone. He had told me during the 1984 interview he felt confident to leave the university in the capable hands of his friend Emory Lindquist, who “could quiet the troubled waters.”

Dr. Corbin was only 46 years old when he left the presidency. Yet his 14-year tenure saw a doubling of undergraduate enrollment, a tripling of graduate students and a quadrupling of the university budget.

The number of volumes in the library had doubled and appropriations for books had increased tenfold. Fourteen buildings had been planned or added to campus, including one he had the foresight to invite Frank Lloyd Wright to design. Started in 1959, the building was dedicated to Dr. Corbin after he left the presidency.

Even though cancer was consuming him, in March 1990 he requested I track down Bill Moyers’ videotape series on Joseph Campbell’s “The Power of Myth.” Remaining a scholar until the end, he wanted it to watch when his eyes tired from reading.

Also a gentleman, he donned a jacket whenever I brought items to his house and, even though he had to use a cane, insisted on walking me to the door when I left.

When he had retired from teaching in 1987, he asked that no announcement be made. Just as quietly, he left this life on Nov. 3, 1990. He had spent 50 of his 73 years affiliated with the university, first as a student, then as a faculty member and president.

Then he died as he had lived: thoughtfully and with great dignity.

Cynthia Mines is publisher/editor of the Wichita Times and a free-lance writer whose articles have appeared in such papers as the Los Angeles Times.

THE HEALER

By James Rhatigan

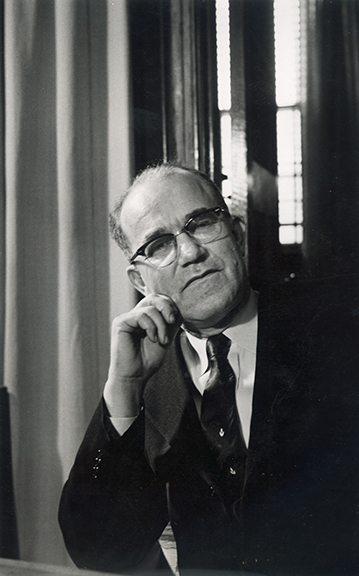

Emory Lindquist came to the University of Wichita in 1953, as a tenured “University Professor.” He had just completed a decade as president of Bethany College in Lindsborg, Kan., when his longtime friend, Harry Corbin, asked him to come to Wichita.

The designation “University Professor” was created by President Corbin solely for Emory.

It meant that Emory would not have to teach out of any one department. Indeed, in his years at the university he would teach courses in ancient and medieval political theory, Western Civilization and English history.

He taught several courses in the department of religion, which he used to explain to students the relationship of faith and scholarship. His graduate courses introduced students to the classical literature he first had been exposed to at Oxford.

Emory was involved with a number of others in preparing material for President Corbin as the effort to gain admission to the state system of higher education heated up.

He was not a public figure in the battle, but did offer support and counsel to President Corbin.

The controversy over admission to the state system ended successfully in 1963, after a fractious fight involving both houses of the legislature, newspaper commentaries statewide and opinions everywhere about the wisdom of Wichita’s entry.

It came as a surprise to many when, in May 1963, President Corbin resigned. He felt that he had used up all of his political capital in the fight for admission and it would be better for a new leader to assume responsibility. Many rallied around Emory Lindquist. It would be difficult to imagine anyone more qualified.

There was only one problem: Emory did not want the job. Emphatically. When the five-member search committee visited him to encourage his candidacy, he is reported as becoming exasperated and finally saying, “Thank you, but goodbye.”

His lack of interest was well grounded. His work at Bethany had been a consuming commitment. He did not enjoy the social side of the president’s life. A teetotaler, he found social occasions involving alcohol tedious and uncomfortable.

His general interest in small talk was quite low. He recognized the importance of fund-raising during his Bethany years, but didn’t like it and felt he wasn’t very good at it. He knew administration and budgeting were important requirements of a president’s job, but he didn’t enjoy this work.

His core interests and values were faith and scholarship. In U.S. history, the presidents of religious colleges served as moral and spiritual leaders. These were not roles to be entered into lightly. Although fitting perfectly in the Swedish Lutheran institution he had headed, these were roles not required in the secular university.

Emory loved Bethany, but Irma Lindquist has said that one of the happiest times in his life is when he resigned as president. Inspiring others was giving way to the work of survival.

There is some irony in noting that near the top of Emory’s reasons for objecting to serving in another presidency was his scholarship. His skills as a teacher and writer were excellent and widely recognized. He came to believe this was his true calling. He had studied at Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar and those years cemented his interest in what he called “the life of the mind.” This was no cliché in Emory’s life.

Thus the search committee moved on without Emory, and 45 candidates emerged. Yet in many places, the search committee encountered Emory’s name. When members of the committee met with University of Illinois President David Henry to secure and review names of those being considered, he asked about Emory Lindquist.

Wasn’t he on the faculty? A former president? A Rhodes Scholar? Respected throughout the state of Kansas? Well, yes. He encouraged the committee to revisit this potential candidate.

Representatives of WU’s board of regents got Emory to agree to another visit, and they enlisted community people to call him and offer their support. This approach gave him pause and he yielded a bit, but then left for Sweden for a long-planned trip with his family.

Dr. Cramer Reed reports “chasing Emory all over Europe” so that he could tell him that the regents had voted unanimously in favor of his candidacy. After some family discussion, Emory agreed to come back to the United States for a few days.

If he was going to consider the matter any further he had some conditions that would have to be met, and he also wanted to meet with Chancellor Clark Wescoe at the University of Kansas, someone he admired and trusted.

When he returned to his family, Emory was divided in his thinking, worrying aloud and experiencing a mild malaise rather than the euphoria many would feel after being sought for such a position. One evening his daughter, Beth, then 15, asked him to go for a walk.

Emory’s account of that day: “We walked quietly for a considerable distance along a low gray closure off a meadow where sheep were grazing. Then Beth stopped, embraced me and said with considerable emotion: ‘Dad, you can do it.’”

This occasion tipped the scale; Emory took the position. His acceptance telegram gives a good glimpse of his feeling: “I have come to the point of reluctantly accepting the post offered at least for a term long enough to cover the transition period. My decision is based exclusively upon (the) assumption that an emergency exists and that no other reasonable solution is available. If this be the true situation, I will in faith do the best I know in the assignment.”

One wonders if there is an acceptance letter in the history of higher education quite like that one.

He spent his inaugural year preparing for the first state budget, mindful of the scrutiny it would receive. He was well aware of the opponents in both chambers of the legislature and on the Kansas Board of Regents, members of which had just voted 0-9 against WU’s entry into the state system.

He also was aware of the conditions attached to WU’s admission into the state system, conditions that irritated many. For instance, WSU was to be an “Associate of the University of Kansas”; any doctoral programs were to be done jointly, the assumption being that the university did not have faculty of that caliber.

It speaks to President Lindquist’s powers of reconciliation that by the end of his five-year tenure, such conditions had all quietly disappeared.

Emory’s expectations for WSU were modest but insistent. The university he envisioned was years away; his job, he felt, was to lay the foundation, to broaden the achievements of President Corbin and those who came before him.

While at times he seemed burdened by his responsibilities, this never kept him from a rhetoric of achievement that bolstered campus morale and diminished arguments on the part of others. He kept intact his skill as a debater. Reason was his ally.

He believed strongly that the future of the university depended on academic quality. Faculty positions were available by the dozen at brand-new Wichita State, and he spent countless hours locating, cultivating and hiring new faculty members.

In his first months of office, he also created a small program for research and governmental programs, an endowment program and a division of student affairs. His sense of community and long years of advocacy for social justice led him to warm relationships with the minority citizens who were the university’s closest neighbors.

He kept alive some small initiatives that on another day would result in the College of Health Professions. He found a way to purchase the Crestview Country Club, thus providing future presidents with more than 120 acres for growth.

By the fall of 1966 the university had grown from its closing WU enrollment of 6,000 to more than 11,000. While the national average for classroom space was about 180 sq. ft., WSU students were shoe-horned into 81 sq. ft. The solution: a longer class day and classes on Saturday. Only toward the end of the Lindquist presidency was space relief forthcoming.

During his time as president, Emory was distracted by a serious athletic scandal and the growing chorus of people who wanted an expanded football program. He regretted these issues occupying center stage, but dealt with them in the same manner as all others, with openness and forthrightness.

In his second year as president, he was selected as the Outstanding Citizen of Kansas, an honor that seemed to symbolize not only his own significant accomplishments, but also a wider acceptance of Wichita State. Emory never yielded to the meanness of the moment and looked beyond difficulties to the future that others would inherit from his efforts.

When he retired as president in 1968, many people lauded the attributes of this dedicated scholar and leader. But the person who perhaps expressed it best was an early opponent on the Kansas Board of Regents who said: “Of all the civilized men I have known, Emory Lindquist is perhaps the most.”

James J. Rhatigan, WSU dean emeritus of students, based this writing on his long association with the Lindquists, Craig Miner’s Uncloistered Halls and Emmet and Marion Eklund’s The Difference He Made.