Press in 1959. Auerhahn and its

successor, Dave Haselwood Books,

published the works of many Beat artists.

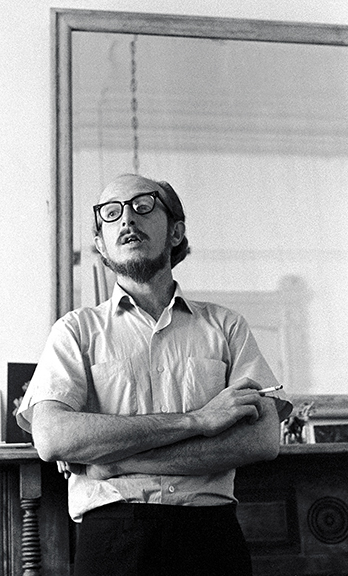

David Haselwood © Larry Keenan

The auerhahn is a secretive German bird of the forests, grouse-like, green and grey, with red hooded eyes, whose mating call is its only giveaway to the hunter’s limit of one per lifetime, for it is rare, extremely elusive, and when cooked, tastes of turpentine.

"The name of my publishing business was Auerhahn — it’s a big European grouse,” David Haselwood ’53 recounts from his Sonoma County home.

The lilting voice of his granddaughter playing nearby provides a musical soundtrack to our phone conversation.

“Looking back, I don’t really know why I chose that name. I must have had a perturbation of the brain. But I loved birds, and I liked the mysteriousness of this one. It was rare and secretive — and lived deep in the forest. I never saw an auerhahn.”

But he did explore the bird’s environs during a stint in the U.S. Army as a journalist and photographer stationed in Europe from 1955-57.

In A Bibliography of the Auerhahn Press and Its Successor Dave Haselwood Books (1976), Haselwood, who graduated from the University of Wichita with a degree in English and then spent a year as a graduate teaching fellow under WU’s English department chair Robert G. Mood, explains his decision to enlist in the service this way: “In 1955, I wrote the last poem and since all my friendships and connections had dropped out leaving me empty of any desire to continue living a life that promised to produce vegetables and no meat, I joined the Army.”

It was while in Germany that the idea of a career in publishing first came to him, via correspondence with his San Francisco-based friend Michael McClure fs ’55, whose first book of poems, Passage (1956), was being published by Jonathan Williams’ Jargon Press.

“Jonathan was having books printed in Germany because of the high quality and low cost,” Haselwood says, “and I began looking into things.”

The Exterminator

Burroughs, William S. & Brion Gysin. The Exterminator. San Francisco: Auerhahn Press, 1960.

Born in 1931, Wichita native Dave Haselwood entered WU at the age of 16 with plans to become a doctor. The young pre-med student came to realize, however, that the money to fund this educational venture wasn’t available to him.

Besides, he was learning that “beginning chemistry was boring” and, although the life sciences — human anatomy and botany, in particular —would be of deep and lasting interest to him, nothing fired his imagination like literature. “This,” he says, “was fun.”

Haselwood credits his mother with sparking his interest in reading, an interest that blazed, he says, at WU: “After the Army, I considered finishing my master’s degree at San Francisco State. The entrance exam covered an enormous list of books. When I got the results, I discovered I had scored in the top 99th percentile. That happened because of a very well-rounded education at the University of Wichita — because of stimulating fellow students and professors.”

Robert Arnold ’56, a political science student at WU, remembered Haselwood as being part of the university’s “literary group.” Before his death Jan. 11, Arnold recalled, “There were all sorts of groups in college, of course, all based on particular interests — music, art, literature, politics, science, you name it. Groups overlapped, especially at parties and at Manning’s, which was the unofficial place to go — you went there if you were a bit of a bohemian. I think one thing many of us shared was a sense of restlessness.”

Corban LePell ’57/59, art professor, now semi-retired, at California State University-Hayward, paints this backdrop to 1950s student life at WU: “I remember Morrison Library with its old-time character,” he begins and adds carefully: “I’ve taken away powerful influences and many good memories from Wichita, but it was a terribly barren place, culturally. It was straight-laced, white, bigoted. The university was a sanctuary for many of us.”

Artist Bob Branaman fs ’59, a pioneer of comix style who now lives in Los Angeles, says, “I respect Kansas, but there was stagnation there — and oppression. There was also a vital fermenting energy.” That seething energy sent to flight literally scores of Kansas artists, many of whom would later be labeled Beat.

Haselwood, McClure and Bruce Conner fs ’55 left Wichita in a first migration; Branaman, LePell, Jim Davis ’59/63, Bruce McGrew ’61 (1937-99), Joan Pepitone ’69 (1932-77), Charlie Plymell fs ’61, Glenn Todd fs ’58 and others, in a second.

Lee Streiff '55, a retired Wichita educator, comments, “A defining peculiarity of Wichita’s culture was a slow-motion exodus that ebbed and flowed, carrying the youth of Wichita out across the continent. Sometimes they stayed where the flood had carried them, sometimes they returned — only to push on again.”

An inordinate number of WU-educated poets, painters and printers pushed on to San Francisco, Haselwood by way of Germany.

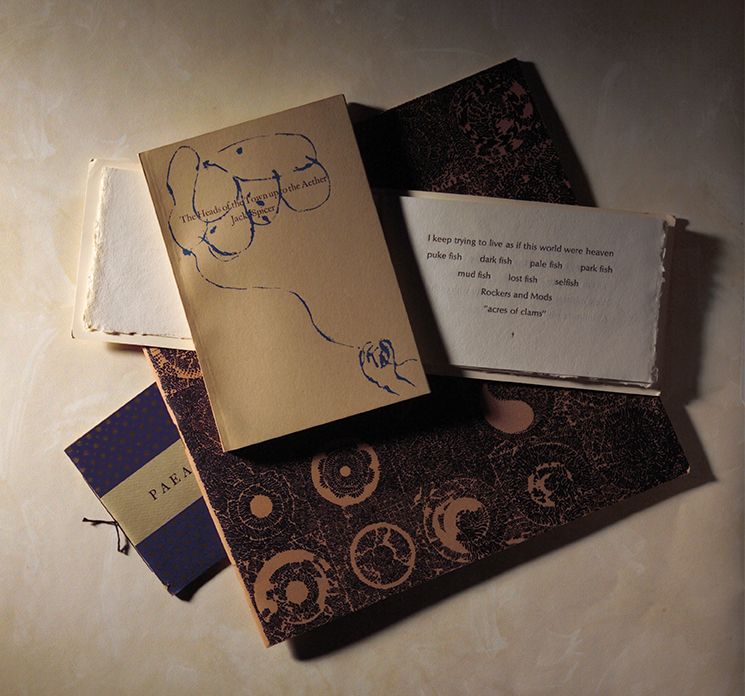

Heads of the Town up to the Aether

Spicer, Jack. The Heads of the Town up to the Aether. San Francisco: Auerhahn Press, 1962.

In 1957, Haselwood settled in San Francisco where he moved into the Wentley Hotel on Polk and Sutter. There, he joined the vanguard of Beat artists who were cutting their art against the grain of contemporary culture.

A short list of painters and poets whom Haselwood “drifted around San Francisco talking endlessly with” includes McClure, Conner, Philip Lamantia, Robert LaVigne, Jesse Sharpe, Lew Welch, Philip Whalen and John Wieners.

As different as they and other Beat artists are from one another, their commonalities illustrate a textural shift in not only 20th-century art forms but also society. They sought truth through visions, dreams and other nonrational states.

They looked for spirituality from largely unplumbed sources — society’s dispossessed and the Far East, for example. Their uniquely personal journeys of exploration proved powerful artistic subjects. Four decades and counting later,?Haselwood is still moved by the power — and the spirit — of those counterculture artists.

“The ’50s were grim,” he says. “But there were these artists who were trying to break loose from the reductionism of American culture. When I first saw their works and read their words, a door opened for me. I thought, ‘You can break out. You can be doing what your heart tells you to do. They’re doing it.’”

In A Bibliography, Haselwood reports, “During the summer of 1958, I read manuscripts that had a more powerful effect on me than anything else I had ever read. I wanted to see them in print, not in five years, but immediately.”

Yet it was a rare publishing house that published any of the artworks that so impressed Haselwood. He says, “The large houses were for the main part cowardly, without visionary foundations, strictly commercial or controlled by academies.”

The Auerhahn took flight.

The New Handbook of Heaven

di Prima, Diane. The New Handbook of Heaven. San Francisco: Auerhahn Press, 1963.

An early Auerhahn press release announces, “The publisher wishes it known that this is the first press on the West Coast seeking to print the works of the younger poets — in co-operation with them. The purpose of the press is to make available the works of new writers in fine printing.”

LePell says, “Auerhahn Press was quite remarkable for two reasons. First, it was very risky stuff to print the new writers. Second, although Auerhahn publications were inexpensive, they were produced as the best publications they could be.”

Underscoring LePell’s first point is a 1960 letter from William Burroughs to Haselwood about The Exterminator project. It reads in part: “I think you realise how explosive the material is. Are you willing and able to publish?” The book was released that same year.

Haselwood explained his mission for Auerhahn in a 1962 Wichita newspaper article: “It seemed to me that if a writer is expected to devote all his energy, and honesty, to producing a work that can be called art, then the firm that publishes that work should give it a setting and presentation that makes some small attempt to live up to the content.”

After first working with a commercial printer on Wieners’ Hotel Wentley Poems (1958), Haselwood determined to “personally print any book the press decided to do.” He assembled a print shop that included a Hartford letterpress and set to learning the craft while holding a job sorting mail at night at the Rincon Annex Post Office.

The press’ debut book was Lamantia’s Ekstasis (1959). In a 1976 interview, Haselwood describes some of his first challenges with hand-printing: “Lamantia’s poems I do not read on the page; they are written in the air and possess me entirely. Trying to set them in type proved almost impossible; the poems are mostly short and I found that I had memorized the poem by the time it was ready to be printed and therefore I was unable to proofread them with any accuracy. So the book has several terrible typographical errors in it. I learned that in printing you can’t be too meticulous or too attentive to the most minute details.”

Next up was McClure’s Hymns to St. Geryon (1959). Haselwood remembers, “The idea for the presentation of these poems came to me in a vision while working at the Post Office: the whole book in 3-D and color. It was printed just that way with almost no changes. McClure’s poems are so powerful and demanding that on several occasions I became almost physically ill while setting and printing them; they are direct blows to the solar plexus and would change everything if people had the guts to take the full blow of them just once.”

Although financial woes plagued Auerhahn, remedies were conjured up. On Aug. 29, 1959, for instance, 12 poets read and Conner and LaVigne staged “a spectacle of objects” for a fund-raising event called Mad Mammoth Monster Poetry Reading & Parade.

Among the next-day newspaper coverage was an article by Lewis Lapham introduced with a three-line headline: “A Big Night in North Beach: The Poets Cry Out: Zen Nuts, Hippies, Squares.”

Lapham’s copy includes this: “David Haselwood, publisher of the Auerhahn Press, a lean man with a mustache, smiled benevolently on the crowd as they filed out.”

Funds raised bankrolled Auerhahn’s next endeavors, Whalen’s Self Portrait, From Another Direction (1959) and Lamantia and Antonin Artaud’s Narcotica, a 75-cent, 16-page “attack on narcotics laws, law enforcement agencies and the general stupidity of the American public,” as described in A Bibliography.

While working on Whalen’s Memoirs of an Interglacial Age (1960), Haselwood wrote, “The first and final consideration in printing poetry is the poetry itself. If the poems are great, they create their own space; the publisher is just a midwife during the final operation, and if he has to do a lot of dirty work that’s the way it should be. Contrary to what a lot of people including publishers think, publishing is not a gentleman’s profession; it is the profession of a crook or a madman.”

Dark Brown

McClure, Michael. Dark Brown. San Francisco: Auerhahn Press, 1961. [Second edition, Dave Haselwood Books, 1967.]

Haselwood took on a partner, Andrew Hoyem, in 1961. By then, a number of Kansans had arrived in San Francisco — including Branaman, who shared living quarters with Haselwood for a time, and Todd, who later worked as a pressman and editor at Arion Press, which Hoyem founded after an amicable dissolution of his Auerhahn interests in 1964.

Todd remembers the partners at work at 1334 Franklin Street: “The Auerhahn was a small press in a small room. Andrew would be setting type, and Dave running the press, passing single sheets of paper through. They’d be in their blue printer’s aprons.” Branaman adds, “Dave looked like someone out of Dickens to me. His shop was a center for artists. It was a well-known center of the culture.”

Another of San Francisco’s cultural hot spots was the Batman Gallery, first owned by William Jahrmarkt, a.k.a. Billy Batman, whose art interests leaned to the visionary, the experimental and the mystical.

According to Jack Foley in O Her Blackness Sparkles! The Life and Times of the Batman Art Gallery, 1960-65 (1995), the opening of the gallery was a “spectacular affair” and featured 99 pieces of Conner’s work. Auerhahn produced the announcement.

In 1962, the gallery was sold to Michael Agron, a psychiatrist and UC Med Center associate professor who researched LSD as a therapeutic tool. Collaborating with Haselwood, Agron conceived of each exhibition’s announcement as a work of art. The first Agron show, Master-Bat, showcased the works of, among others, Conner and Branaman.

As the Beat scene faded with the ascent of Hippie culture, Haselwood continued to collaborate with artists on Dave Haselwood Books projects. He worked for a time at Arion Press and designed books for other presses, but his interest in publishing had waned by the close of the ’60s. It was time, he says, to choose another path.

After the Cries of the Birds

Ferlinghetti, Lawrence. After the Cries of the Birds. San Francisco: Dave Haselwood Books, 1967.

Always a lover of the outdoors, he became a landscape architect. The husband, father and grandfather is also an ordained Buddhist priest. Interested in Zen since the early ’60s, he says he was given one of his most valuable lessons early on in his studies.

As he explained to David Chadwick in 1995: “What happened is that every time I’d sit down on the pillow I’d start crying — not sobbing, but tears would start pouring down and I didn’t have any idea what this was. This went on and on, so finally one day I went to Suzuki-roshi and said, ‘I would like to talk to you.’ So he set up a dokusan and I walked in there and sat down and I told him, ‘I’m leaving. I don’t know what it is, but I can’t deal with it.’ These are the words he said to me exactly ’cause I never forgot them. He didn’t say you should try to stay or do this or do that. He said, ‘You try and you try and you fail, and then you go deeper.’”

Haselwood went deeper. Like an auerhahn hunter, he searched the deep forests — and flushed the rare and elusive bird for us to see.