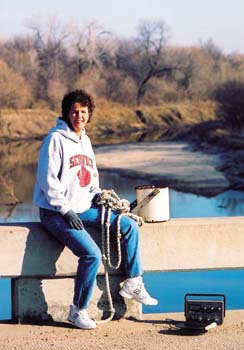

gear she used to collect water samples from

the Little Arkansas River. McGinn and her

husband Mark ’75 farm nearby.

Of all the issues that pit environmentalists against agricultural producers, it’s a safe bet that the biggest divide is over water.

Pick a state. Name a river. Chances are that a disagreement or an outright battle over some aspect of water is occurring there. Throw politics and business interests into the fray and things get especially interesting. Finding a solution that pleases everyone is a real balancing act.

Carolyn McGinn ’83, commissioner for Sedgwick County’s 4th District, is familiar with that tightrope. In fact, McGinn is uniquely qualified to negotiate it skillfully — and with grace.

Not only does she hold college degrees in business and environmental studies, she is also a politician who represents a diverse urban and rural constituency, individual members of which are often at cross-purposes.

Most importantly, she and husband Mark farm near the Little Arkansas River northwest of Valley Center, Kan., and their farm is no different from dozens of other small farms located within the river’s watershed. Water matters to her.

Although Mark McGinn ’75 has worked at Cessna Aircraft Co. for 25 years, farming is his heritage; the McGinns’ 1,000 acres of grain production was seeded by his family’s 320-acre homestead, land worked previously by his grandfather and his father.

“After we married and I got involved with the farm,” Carolyn comments, “I realized that farming is really a small business as expensive as any other, because you have to be able to balance being in operation and staying within regulations.” Consequently, she enrolled at Wichita State and earned a bachelor’s degree in business administration with an emphasis in marketing. She explains, “Selling our crops has a lot to do with marketing, especially internationally.”

Through McGinn’s involvement in the Sedgwick County Farm Bureau and the Andale Farmer Co-op, she became increasingly aware of the mistrust — and sometimes downright animosity — that farmers and environmentalists have for each other. She had long realized that farming’s best management practices included responsible stewardship of the land, which in turn led to a series of events that have since shaped her career and her calling.

To learn more about the environment relative to smarter and better farming, she undertook the master of science program in environmental studies at Wichita’s Friends University. For her thesis, she decided to test a widely held environmental assumption.

“Not so long ago,” she explains, “farmers and ranchers were viewed as the primary sources for what’s called the nonpoint-source pollution of rivers — polluted runoff upstream containing farm fertilizers and livestock waste, rather than from an identifiable source like a storm drain. The city of Wichita believed that the Arkansas River’s periodic high levels of e. coliform bacteria, for example, were coming from the livestock industry upstream.”

Having lived upstream for quite a few years, McGinn knew that there was no livestock industry there, so that particular pollution source, and by extension others, had to lie elsewhere. Enlisting the help of Vaughn Weaver ’93, a city environmental water quality specialist whom she had met earlier in a grass-roots environmental-interest group, McGinn made the Little Ark her new best friend in 1998.

Her water-testing project was funded by a grant from the Kansas Department of Health and Environment, and the city of Wichita provided a laboratory, as well as Vaughn’s assistance as in-kind support. This early collaboration toward a mutually beneficial goal became McGinn’s mantra down the line.

Water sample collection, recording, preservation, chain-of-custody protocols and analysis were conducted according to stringent science.

A five-mile stretch of the Little Ark was monitored monthly at three sites over the course of a year: Samples were taken from the bridge at the Harvey-Sedgwick county line, from a point of adequate flow in the river at 85th St. North and from the bridge just west of Valley Center.

Measurement parameters included dissolved oxygen, suspended solids, ammonia, nitrates, phosphates, fecal coliform, pesticides and herbicides.

McGinn discovered that the base-flow health of the river was generally good and that pollutant levels typically rose after a storm event, which strongly suggested that watershed runoff non-attributable to any specific source was the culprit.

And she found that pollution generally increased as the population increased downstream, which suggested that upstream farmers couldn’t be scapegoated anymore.

over the course of a year from three sites

along a five-mile stretch of the Little Arkansas.

She concluded that the base-flow health of

the river was generally good and that pollution

levels rose after storms.

She used the results of the study as talking points at numerous schools and co-op meetings. One of the easiest ways to prevent nonpoint-source pollution at little expense, she told farmers, is not to work the soil right up to the river’s edge; instead, a grass buffer helps take up nutrients and slow down erosion and runoff.

“It was fortunate that Carolyn took up this cause,” Weaver comments. “She’s a farmer herself, so her results gained instant credibility with the rural population.”

Similarly, better practices on the farm also make sense in the city.

As one example, McGinn says, “Center pivot irrigators put water on fields much slower and lower to the ground. There’s not as much evaporation or runoff. Farmers save on fuel costs, and what water is lost goes right back into the Equus Beds aquifer, not into a ditch, down a drain and into the river. If our urban neighbors watered their lawns more like this and not so often — which is actually better for the grass — they would help the environment and save money.”

Through her holistic view of the problem, she became an important liaison between groups that often have trouble finding common ground. “As a small-business owner, a farmer, a rural resident, a representative for an urban population, a county official who has dealings at the state level and an environmentalist, she works hard to balance the concerns of very diverse constituencies,” Weaver says. “She’s as unique and valuable as her project turned out to be.”

In fact, it was when that study was nearing completion that McGinn decided to run for the Sedgwick County Board of Commissioners: “County government deals with crucial issues like solid waste, environmental impact, the cost of doing business and the growth of communities regarding land, water and watersheds. As a county resident, I really wanted to bring to that table information, experience and questions about how we can positively affect inevitable change.” She was elected to the board in 1998 and served as commission chair during 2001, after being named chair pro tem in 2000.

According to Weaver, the board is fortunate in that each of its five members has a specific area of expertise. Board chairman Tom Winters says, “Because of her knowledge and even-handed commitment, Carolyn is the person we look to when a water issue is on the table.” The commission is currently exploring alternative sewer disposal systems for homes in the most rural parts of the county. Winters explains, “Sewer ‘technology’ out there is 75 to 100 years old. A cost-effective and environmentally sound upgrade is in order, but since we have to balance all kinds of considerations, we rely on Carolyn’s input.”

As McGinn realized early on, cities versus small towns, business versus the environment, government versus government and urban amenities versus irreplaceable wildlife have never been a working model for success in resolving any issue, especially where water is concerned.

“We’re all in this together,” she says, “and it’s a day-to-day balancing act.”