Gerald Norwood ’74, an account manager with Xerox Corp.

in Wichita, is leading efforts to not only organize a Dunbar

reunion slated for June 8-10, but also to explore and

document the all-black elementary school’s unique history

and place in the community.

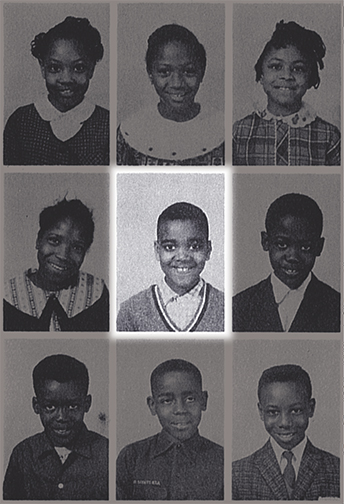

Bright and early every school day back in 1959-60, Gerald Norwood walked from his family’s Wichita home in the 500 block of Wabash to Dunbar Elementary School at 923 N. Cleveland.

Inside its big front doors, he and his fellow second-graders learned about all kinds of things from Mrs. Noiles: about foods and seeds, animal adaptations to winter weather, building strong bodies, reading tonal patterns, playing musical instruments, even (so says a school yearbook) “expressing ourselves through the use of the tape recorder.”

Today, Norwood ’74, an account manager with Xerox Corp. in Wichita, is leading efforts to not only organize a Dunbar reunion slated for June 8-10, but also to explore and document the all-black elementary school’s unique history and place in the community.

“We’re not just planning this reunion for fun,” Norwood relates. “We want to share the rich heritage of this school and this community.”

The heart of the thriving African-American neighborhood that Norwood grew up in was centered around Ninth and Cleveland.

The Dunbar Theater at 1007 N. Cleveland — built in 1941 — was just up the street from the Dunbar school, while the Turner Drug Store, an ice cream shop, and other small business enterprises were across the street and only a marble’s throw from the school.

Churches, including the New Hope Baptist Church at Ninth and Ohio, barber shops, hair salons, juke joints, cafés, a grocery store, a YMCA and the Phyllis Wheatley children’s home were all nearby.

“This used to be the black downtown,” says Dale Black ’73, who is among the group of Dunbar alumni working with Norwood on reunion plans that include a building tour of the Dunbar campus, a banquet and a dance. Black’s key project is putting together a video covering the history of the school from 1927-1971, the year it was closed because of the public school district’s desegregation efforts.

Although the Dunbar building still serves the surrounding community as an adult and early childhood education center, when the neighborhood lost its only elementary school, it lost one of its main community anchors, Norwood says. Through his eyes, as soon as former Dunbar students began being bused to other schools, the neighborhood began losing some of its vitality — or as he puts it, some of its “connectivity.”

“The Gang’s All Here”

In Norwood’s and Black’s quest to put together a history of their old elementary school, they’ve interviewed many Dunbar graduates and former teachers. Nearly every one of them, they say, recalls with pleasure the school’s famed fiestas, as they do. The school’s 1959-60 yearbook includes a series of fiesta photos showing students wrapping a festive Maypole. The exuberance of the day is evident.

Elementary School once served

is called the McAdams Neighborhood.

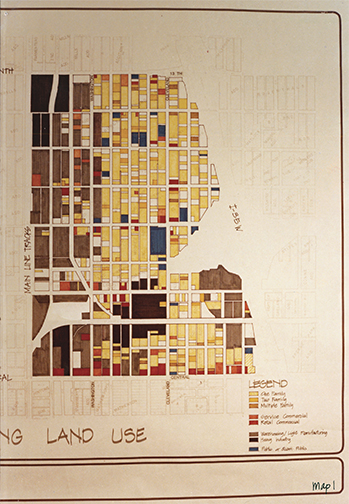

The map pictured above, which is part

of the 1977 McAdams Neighborhood

Land Use Study by Oblinger-Smith

Corp., shows the outline of the

community. Map courtesy of WSU

Libraries Special Collections.

“Our teachers looked like us and lived in our neighborhood. They were prepared, skilled teachers who instilled a sense of hope, of potential in us. They knew us. They really knew our capabilities,” Norwood says. He adds, “It was a golden period, a time when neighbors knew neighbors.”

For Norwood, the upcoming reunion is in large measure a chance to recognize the Dunbar teachers and principals (including James Anderson, the namesake of Wichita’s Anderson Elementary School), who so positively influenced him and so many other Dunbar students, including Black, who was a fourth-grader in 1959-60, Karla Burns ’81/81, who was in kindergarten then — and Linwood Sexton ’48, who remembers racing to school some two decades earlier in an attempt to reach Dunbar grounds before the custodian rang the school bell.

“I went there, hmm, probably around 1931,” muses Sexton, an area sales manager for Hiland Dairy in Wichita and a well-known civic leader who was awarded the WSU Alumni Achievement Award in 1977. “My family lived at 1014 Cleveland. There were many businesses near our home and the school.

“There was the Shadid Grocery, Purcell’s Drug Store. My dad had a little drycleaning drop-off for his business. There was a shoe shop, a bookstore, Spencer’s Restaurant, quite a few restaurants — of course, you couldn’t eat anywhere else. It was a forced neighborhood because that was the only place you could live. But the spirit in the neighborhood and at school was terrific because we were all in the same boat.”

Sexton, whose late wife, Delores (Berry) ’53, was a sixth-grade teacher at Dunbar in 1959-60, adds that “blacks were not able to teach high school in those days. They had to teach at segregated elementary schools.”

Dunbar Elementary School (as well as the Dunbar Theater) was named for Paul Laurence Dunbar, the first black poet to gain national critical acclaim. His poems, essays, short stories and other literary works often addressed the difficulties African Americans encountered in their fight to achieve equality in the United States.

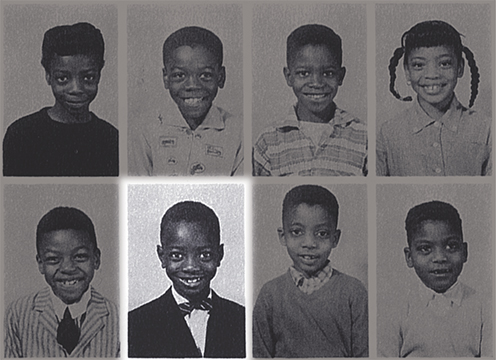

bachelor’s degree in anthropology

at WSU, was one of Mrs. Alford’s

fourth-graders in 1959-60.

The son of former slaves, Dunbar was born in Dayton, Ohio, in 1872 — and was 24 years old when the U.S. Supreme Court supported, in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), a Supreme Court of Louisiana ruling upholding racial segregation, commonly referred to as the “separate but equal” doctrine. Not until 1954, in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision, was the doctrine struck down. And it was another 17 years before Wichita desegregated its schools, closing Dunbar in the process.

McAdams Neighborhood

The community that Dunbar Elementary School once served is called the McAdams Neighborhood. The map pictured above, which is part of the 1977 McAdams Neighborhood Land Use Study by Oblinger-Smith Corp., shows the outline of the community, while The McAdams Neighborhood Revitalization Plan of 2003 roughly defines its boundaries as 17th Street on the north, Hydraulic on the east, Central on the south and Mosley on the west.

Over time, man-made edges and barriers have physically fragmented the original neighborhood into a number of sub-areas. For instance, the I-135 freeway and associated floodwater canal system divide McAdams’ main residential area. Having no turning lanes into the neighborhood along 13th Street creates a further barrier.

According to the 1971 Sedgwick County Assessor’s Annual Enumeration and Survey Data, the neighborhood’s racial composition the year of Dunbar’s closing was “1,240 black, 79 other and 18 white.” Census 2000 data shows that the population declined by about 20 percent over the last decade and that African Americans continue to constitute the largest segment, about 76 percent, of McAdams’ racial composition.

McAdams Neighborhood is, according to the 2003 revitalization plan, “characterized by structural, market and community decline to a level where large-scale interventions are needed to create economic and social stability.”

“Road to Zanzibar”

“Wichita’s newest theater, the Dunbar, located at Ninth and Cleveland, will be formally opened this evening at 7 o’clock with officials in both the colored and white race taking part,” reports the opening paragraph of an Aug. 15, 1941, Wichita Eagle story about the theater’s grand opening.

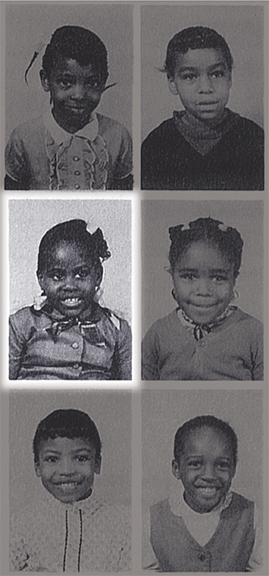

Gracey’s kindergarten students

in 1959-60, went on to earn two

bachelor’s degrees from WSU,

one in speech and theater, the

other in vocal education.

“This modern theater, which helps round out the community center, seats 500 persons, and will carry double feature programs, with selected short subjects and cartoons added to fill the various bills,” the article continues, going on to explain that the premier program features “Road to Zanzibar, with Bing Crosby, Bob Hope and Dorothy Lamour; The Gang’s All Here with Mantan Moreland, dynamic colored comedian, and Frankie Darro and Marcia Mae Jones. A color cartoon completes the program.”

Had the Dunbar opened its doors a mere two years earlier, its grand opening might have featured Gone with the Wind (1939) — and one of Wichita’s own: Hattie McDaniel (1895-1952).

McDaniel was the first African American to ever win an Academy Award, for her role as Mammy in the award-winning movie. Having left school in 1910 to join a minstrel show, she went on to land major roles in Judge Priest (1932) and Show Boat (1936), in which she performed the role of Queenie.

A half-century later, Karla Burns also tackled the role of Queenie, most notably in a 1990 Broadway revival of the musical, for which she earned a Tony Award nomination and a Drama Desk Award.

For the London production of the show, she was presented Great Britain’s Olivier Award. She relates that when she accepted the honor, “I didn’t have to walk through the kitchen,” referring to McDaniel’s entrypoint to the awards ceremony. “I could walk through the front door.”

The two award-winning performers grew up in homes only 10 blocks apart.

Back to the Old Neighborhood

March 25, 1950, is the date of the formal installation of the Delta Mu chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha at the University of Wichita. Established in 1906, Alpha Phi Alpha is the first intercollegiate fraternity established by African Americans. In the chapter’s first year at WU, there were “eight actives and 11 pledges in the newly organized fraternity,” according to the 1950 Parnassus. Their fraternity house was well off campus. It was a stately rock home at 1301 Cleveland.

Wichita State with a bachelor’s degree in

religion, was a second grader at Dunbar

Elementary School in 1959-60.

“There were a lot of larger homes that had been built in the neighborhood,” Sexton relates. “Doctors and lawyers … and laborers — we were all there together.”

To address the physical decline of the McAdams Neighborhood over the years, a number of revitalization plans are in play, including a renovation of the Dunbar Theater (Dunbar Theater Redevelopment Feasibility Study Report, June 7, 2006) and the redevelopment of a neighborhood-serving elementary school (Revitalization Plan, 2003).

But the theater remains run-down and vacant, and the most activity the Dunbar campus will have seen in years will revolve around the upcoming reunion. Norwood, as president of the Dunbar Reunion Planning Committee, invites all former students, faculty and staff members to come enliven their old elementary school — and help re-invigorate a neighborhood.

“We had a sense of togetherness,” Sexton recounts. “I still remember our school song.” And it ends with, he notes, “Dunbar’s going to shine tonight.”