A new era of ecology is dawning in America, urged along by unending conflicts in the Middle East, ever-higher fuel prices and increasing concerns about global warming.

Research into alternative energy sources is being funded by some of the world’s largest companies and carried out in laboratories and on college campuses everywhere.

And in garages all across the nation, individual tinkerers are quietly mounting a revolution — a revolution that smells like french fries.

John Harrison doesn’t look like a revolutionary. An associate professor of violin at Wichita State, he lives in Wichita’s ivied Sleepy Hollow neighborhood with his wife, WSU assistant professor of bassoon Nicolasa “Nic” Kuster; the two have been married five years and perform together in the Wichita Symphony Orchestra, in which Harrison also serves as concertmaster.

Yet his mild manner is betrayed by a glint of mischief that shines in his eye when he talks about the pet project parked in his driveway. “I converted a 1982 Mercedes Turbo Diesel 300TD to also run on straight vegetable oil,” he says conspiratorially.

He’s not kidding. As alternative — and ideally renewable — sources of energy are being explored, more and more people today are turning used vegetable oil from restaurant fryers into fuel for their diesel-engine vehicles. Rudolf Diesel’s first engine, built in 1895, ran on peanut oil.

“Basically,” Harrison explains, “if you pour hot veggie oil into a hot diesel engine, the engine happily runs. So the trick is to, one, start the car on diesel and, two, heat the oil in some way. I did this by buying a kit made by a company called Greasecar. I ended up altering the kit a bit, using improved parts and adding an additional electric heater for the oil.”

Diesel fuel is required to start the car and warm up the engine so that the vegetable oil, which solidifies as it cools, becomes hot enough to flow smoothly. Once the system is suitably warm, the driver merely flicks a toggle and the car seamlessly switches over to the liquefied oil.

Harrison is delighted to demonstrate his handiwork to most anyone who asks and in fact advertises his cleverness in vinyl letters across the hatch of his station wagon: “Powered by Vegetable Oil.” Even without that explanation, one sniff is plenty to alert the casual observer to the car’s unusual fuel source: Its exhaust smells like fried food. Harrison wishes to make himself visible as a self-empowered citizen doing his part to improve the world, even though doing so puts him in legal jeopardy.

Mercedes station wagon lurks a

diesel engine — and a few key

modifications that allow the car to

run on recycled vegetable oil.

“Using veggie oil to power a vehicle is technically in violation of the Clean Air Act as I understand it,” Harrison explains. “The violation carries a fine of around $5,000. Nobody has been prosecuted.

The Clean Air Act requires street vehicles to be powered by certified fuels, which means fuels that have gone through and passed rigorous testing by the Environmental Protection Agency. Although thousands of cars have been converted, EPA still hasn’t even started the testing. Private companies such as Greasecar have done the testing themselves — and the fuel passes, burning much cleaner than diesel.”

Justin Carven, the 29-year-old founder of the Massachusetts-based Greasecar company, agrees, pointing out, “Besides cheap fuel, there are incredible environmental benefits. You’re putting less carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than plants take out.”

“I understand the need for certified fuels,” Harrison says, “but I am a bit puzzled that the EPA hasn’t begun testing for veggie oil, as it is beginning to be a common topic of conversation as an alternative energy source.”

Harrison says he would welcome a citation, because it would give him an opportunity to challenge the law in federal court. Some admire his quixotic bent, but others among his fellow “greasers” still fear reprisals from the long arm of the law. One acquaintance “thinks he’s going to be arrested if people know,” chuckles Harrison. “He can’t believe I have a sticker on the back of my car. Whatever!”

Carven admits that the federal authorities have not signed off on his kits, but claims the company is working on it. “Any aftermarket automotive product must go through an evaluation process with the EPA to be certified,” he says. “We’re in the process of doing that.” The legal snag hasn’t hurt sales, though. “We’ve sold about 3,000 conversion kits since I founded the business in 2000, and just last year sales broke one million dollars.”

That kind of money will buy a lot of grease, especially when the stuff can be collected at no cost from restaurants.

“At first, I just bought new oil from Aldi (the grocery chain), and this is still not bad,” Harrison says. “It supports a renewable fuel and supports farmers, and it is cheaper than diesel, though not much. But the real trick is to get waste veggie oil from a restaurant and filter it so that the engine isn’t trying to run on food particles. Building the filtering system turned out to be much harder for me than converting the car, in part because I had no kit to do it. I tried many things and finally have a system that works.”

monitors the filtration process.

Harrison put his ingenuity to the test building his homemade storage and filtration system entirely from repurposed materials, including livestock water heaters, recycled plastic barrels and discarded blue jeans. Once his system was functional and his car conversion was complete, the moment of truth arrived — though it was somewhat anticlimactic.

“Basically the car worked on the first try, more or less,” he recalls. “I actually thought it must not be working when it was working, because the car just switched over without a hitch. But then I smelled the exhaust.”

The average person wouldn’t be likely to go to such lengths — the expense, the time, the effort, the trial and error, the improvisation — to reduce his or her dependence on fossil fuels. But to an iconoclastic thinker like Harrison, who also serves as director of WSU's Center for Research in Arts, Technology, Education and Learning (CRATEL), such concerns don’t even enter the picture.

“Nic and I are environmentalists,” he explains, “and we wanted to encourage conversation about alternative — and especially renewable — fuels. Also, I’d been looking for an excuse to do some car work; I have always wanted to work on a car but could never quite justify it.”

With his greasecar project, Harrison got his wish in spades. Not only did he have to add a second fuel tank for vegetable oil and all the related plumbing, he also discovered much repair was necessary on the existing car before really getting started on the conversion.

“I bought a car that was in pretty sad shape,” he says. “I ended up replacing the brakes, half-axle, exhaust manifold and on and on. I spent a lot more time making the car drivable and reliable than actually converting it. Now it is reliable but there are still some minor annoyances — to fix next summer.”

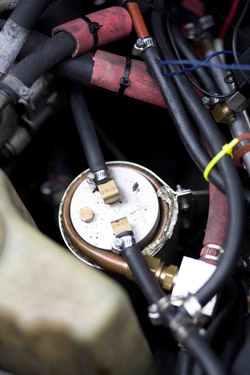

Wichita garage is this homemade

waste oil filtration device, assembled

from re-cycled and repurposed parts.

The machine strains used fryer oil

from a local restaurant, removing

small food particles before the oil is

burned in Harrison's car.

Now that his greasecar is running smoothly, his efforts on the project center on collecting and filtering used vegetable oil. His current source is a local, family-owned restaurant, which he chooses not to identify.

“When the Wichita Eagle wrote a story on this, I told them where I was getting oil at the time,” he recalls with a hint of regret. “The ramifications for the restaurant were not good — they got blacklisted by the major disposer of grease in town.”

That being said, Harrison is at least willing to reveal one secret about where to get the highest quality used fryer oil. “I tried several restaurants,” he relates, “and it is very clear that the Asian restaurant oils are the best. They use oil that’s not as thick as the diners and sandwich shops. And they don’t fry much meat, so there’s not too much lard to clog the filters.”

With mounting interest in alternative fuels, it’s hard to tell what the future holds in store. One promising option is biodiesel, a fuel made from vegetable oil that will burn in unmodified, stock diesel engines; country singer Willie Nelson is a vocal proponent and runs his tour buses and other vehicles on this fuel.

Regardless of what energy source our cars use in the future, Harrison believes it’s a matter of national security — and perhaps even human survival.

“If more people converted their cars, there would be interest in growing crops for fuel. And non-food-grade veggie oil would become an affordable source for consumers wanting to power their vehicles.

Also, more important than the conversion is the conversation it starts in your community and in the world. It’s a wonderful conversation filled with possibility of a future not dependent on fossil fuels.“If we as a nation wish to see alternative fuel supported,” he adds, “we are going to have to create that future in our own grassroots movement — and with enough momentum that our government will follow. It won’t be the other way around.

“We can’t just sit around and wait.”