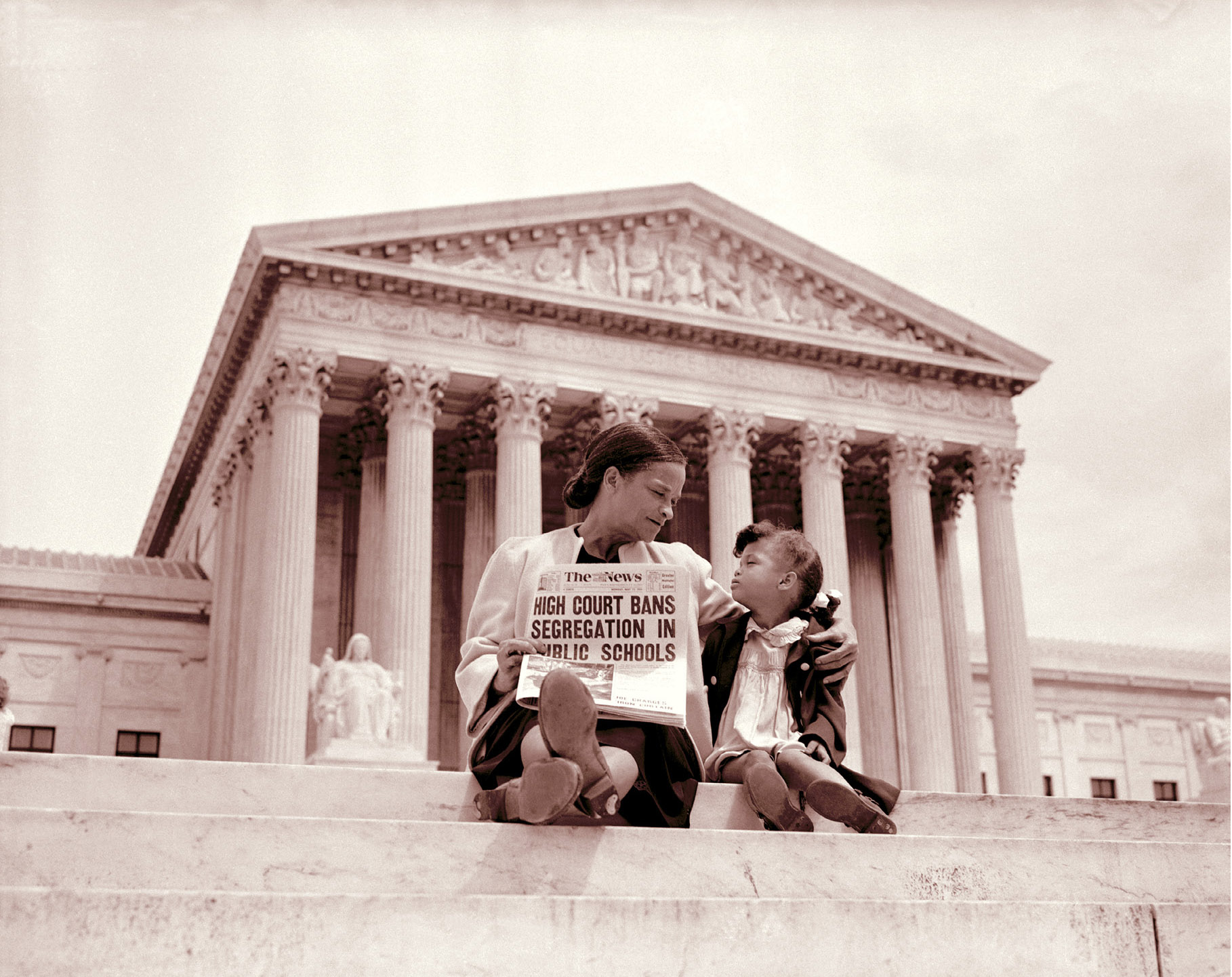

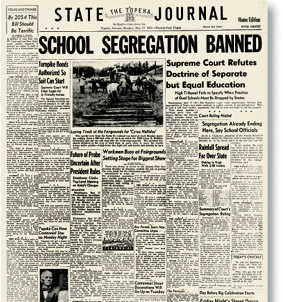

Fifty years ago on May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education, Topeka, Kan., that segregated public schools were unconstitutional. At the time of the high court's decision, I was a 4-year-old African-American kid from a working-class family in Wichita.

I would enter kindergarten in the fall. I lived on a street that divided two distinct neighborhoods: poor African Americans to the south and middle-class whites to the north.

Many of the homes in the African-American neighborhood were what we called "shotgun" houses: That is, standing in the front yard with the front and back doors opened, you could fire a shotgun clean through them to the backyard. Most of the kids in this part of my neighborhood came from families of laborers like my father, who worked as a butcher at a meatpacking plant, and like my mother, who cleaned houses for middle-class and rich white families.

My father and mother attended segregated public schools. After Brown, I had a choice that neither of my parents had growing up: Rather than attend the segregated African-American school several miles to the south, I could attend the white school three blocks to the north.

This was an easy decision 50 years ago: My parents sent me to the white school because of its better facilities and fewer students per classroom. However, during my elementary school years, each school remained de facto segregated — one overwhelmingly white and the other overwhelmingly African American. Today, the African-American elementary school no longer exists, and the white school that I attended is predominantly Latino.

Clockwork Cases

Every 25 years since the Brown decision, the Supreme Court has taken up — almost like clockwork — a case involving race and education, the outcome of which has served as a touchstone of fundamental American democratic values.

In 1978, Allan Bakke, a white student twice denied admission to the University of California, Davis, Medical School, sued the university on the grounds that the preference given to minority applicants disadvantaged white applicants, thereby violating the equal-protection clause of the 14th Amendment of the Constitution. The court, in a divided opinion, invalidated UC Davis' quota system but, at the same time, seemed to uphold affirmative action and the use of race as one factor in considering applicants (Regents of the University of California v. Bakke).

Twenty-five years later, in the summer of 2003, in two cases involving the University of Michigan, the court, speaking through Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, ruled 5-4 that diversity is a compelling national interest and that affirmative action may be used in the college admissions process to achieve diversity, as long as the methods of doing so are "narrowly tailored" (Grutter v. Bollinger).

Twenty-five years later, in the summer of 2003, in two cases involving the University of Michigan, the court, speaking through Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, ruled 5-4 that diversity is a compelling national interest and that affirmative action may be used in the college admissions process to achieve diversity, as long as the methods of doing so are "narrowly tailored" (Grutter v. Bollinger).

The ancestral lineage from Brown to the University of Michigan is clear and distinct. In both instances, the court affirmed that public educational institutions — secondary and post-secondary alike — have an obligation to ensure that "the path to leadership ... [is] ... open to talented and qualified individuals of every race and ethnicity" (Grutter v. Bollinger).

The court first heard oral arguments for Brown in December 1952. (Brown was actually a consolidated case involving five school districts in South Carolina, Virginia, Delaware, Kansas and the District of Columbia.) The court was deeply divided over the issue and therefore took the unusual step of ordering a reargument for Oct. 1953 in the hopes of attaining a unanimous decision or, at the very least, one that would inspire confidence and broad support for its ruling.

However, three months before the reargument was to take place, Chief Justice Fred Vinson unexpectedly died (providentially, some would say later) from a heart attack. President Dwight Eisenhower, whose own views on desegregation were conflicted, appointed as the new chief justice a man not known for the strength of his judicial intellect: Earl Warren, a career politician and former governor of California.

So it was that Warren was sworn in as the nation's 14th chief justice in the fall of 1953 after the court's consideration of Brown had already begun and a mere eight weeks before the decisive reargument was scheduled to take place.

Most interesting is that when he was California's attorney general, Warren had demanded the internment of more than 100,000 West Coast Japanese Americans during World War II. In fact, he had been a member of an anti-Asian organization, the Native Sons of the Golden West.

And yet it was Warren who persuasively championed the court unanimously to rule an end to segregated public schools, and it was he who read from the bench the now famous lines that constitutionally annihilated the separate but equal doctrine that had been the law of the land since Plessy v. Ferguson (1896): "[I]n the field of public education, the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal."

Justice Felix Frankfurter, not known as a very religious man, later called the timeliness of Vinson's death "the first indication that I have ever had that there is a God."

The court's opinion forever connects the desegregation of public education with the use of affirmative action in the admissions policies of colleges and universities: "Today, education is perhaps the most important function of state and local governments. It is required in the performance of our most basic public society. It is the foundation of good citizenship. In these days, it is doubtful that any child may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he is denied the opportunity of an education. Such an opportunity, where the state has undertaken to provide it, is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms."

Vivid Memories

Fifty years later, certain memories stand out: My best friend in elementary school was a white boy who lived in the white neighborhood where I went to school. I recall playing football on Thanksgiving in the fresh, new Kansas snow — he was a pretend Johnny Unitas, the Baltimore Colts quarterback, and I was a pretend Lenny Moore, the all-star running back. Though we walked to school together, I was never allowed by his parents to set foot inside his house.

I have an indelible memory of being chased home across the school playground by my principal, Mrs. Zimmerman, who seemed to my young imagination an exact replica of the wicked witch in The Wizard of Oz. While I can no longer recall the affront that triggered this event, I remember that she never took kindly to the idea of an integrated school or to a young African-American kid who seemed to outshine all of the other kids. The next day, my mother, my grandmother and Aunt Lizzie, three strong-minded African-American women, walked resolutely to school — with me in tow — to confront her bigotry.

I learned many lessons — not all of which the court probably had in mind when it desegregated the nation's public schools. I learned from an early age what it means to be the only dark face in a sea of white faces. I learned what it takes to be the best when the expectations of teachers, students and others lean entirely in another direction. I learned what it means to be the "first" African-American "this" or "that." I learned the burden — imposed by whites and people of color alike — for me and others like me to represent in our life and work not only our own private hopes and dreams, but also the hopes and dreams of an entire race of dark-skinned people.

Brown's legacies are many, and they are powerful. Brown represents the convergence of two compelling movements: one legal, the other social. As important as Rosa Parks and the Montgomery bus boycott are in our nation's history, the civil-rights movement really commences with Brown.

Brown began the long process of legally unraveling a nation of separate parks, hospitals, public transportation, water fountains, public restrooms, libraries, hotels, restaurants, theaters and cemeteries — not only in the South, but in the North as well. It laid the legal foundation by which other forms of discrimination have been eliminated. We are a better and a stronger nation because of Brown.

Good News, Bad News

And yet, at times, it seems that for every step forward that we have taken since Brown, we take two steps back.

There is good news in higher education: When I entered college, nearly 87 percent of college students in the United States were white, about 9 percent African American and the combined total of Asian Americans, Native Americans and others less than 3 percent. Today, nearly 28 percent of those participating in higher education are persons of color.

By contrast, the news in public secondary education is less encouraging: Public schools are resegregating themselves. The Civil Rights Project at Harvard University reports that the average white student attends schools where more than 80 percent of the students are white and fewer than 20 percent of the students are other racial and ethnic groups. Seventy percent of the nation's African-American students now attend predominantly minority schools — a significant increase from the low point of 63 percent in 1980.

Its report goes on to say "the vast majority of intensely segregated minority schools face conditions of concentrated poverty, which are powerfully related to unequal educational opportunity. Students in segregated minority schools can expect to face conditions that students in the very large number of segregated white schools seldom experience." Those conditions include more school violence, less per capita spending and, in many cases, lower academic standards and expectations.

By the year 2050, there will be no majority "race" in America. Even today, the big question is whether it is possible to sustain the vision from which Brown emerged in an America radically different from America 50 years ago.

In many respects, the world, 50 years later, is topsy-turvy. Consider, for example, a San Francisco neighborhood in which Chinese Americans fiercely resist an integration plan that buses its children many miles away, denying them access to the schools close by. Similarly, African-American families in large urban inner cities, like Boston and Chicago, challenge court-ordered busing in favor of revitalized but highly segregated neighborhood schools.

In these instances, how do we reconcile the competing claims of families of color against the integrationist vision of satisfying the public good articulated in the Brown decision?

What shall we do? While there are no easy or even new answers, it is clear we need to redouble our efforts to revitalize neighborhoods and our public education system. The poverty gap and the achievement gap in public education stubbornly persist. We also need to reform the way in which we train public school teachers so they are better prepared to teach effectively in increasingly multicultural and multiracial communities; and we need to provide incentives for our very best college students to seek teaching positions in areas where the poverty and achievement gaps are most prominent.

In doing so, we protect the legacy of Brown and its role in defining social justice and equality in America.

M. Lee Pelton obtained his bachelor's degree from WSU in 1973 and his doctorate in English and American literature from Harvard University in 1984. He became the 22nd president of Willamette University in July 1998.

Lending Wings

When playwright Marcia Cebulska needed powerful visual designs for the May 17 Topeka reading of her play "Now Let Me Fly" — a work that brings the Brown v. BOE saga to life — she called on Mike Wood, executive director of WSU's Media Resources Center.

Wood spent months poring through film and photographs for a montage that aired while actors read the play. He used photos archived at schools in the South and footage from a 1940s film documenting the sad state of all-black schools. WSU's National Institute for Aviation Research pitched in, too, lending a hand in the creation of a 3-D animation morph from the thumbprints that touched Brown's historic documents to a pair of graceful wings.

Wood even "borrowed a bird" from WSU's Chris Rogers to better visualize the image. The reading featured James McDaniel of NYPD Blue as Marshall and Roger Aaron Brown of The District as Houston. Also featured were Yolanda King, daughter of the great civil rights leader; jazz singer Queen Bey; and A&E's Bill Kurtis, as host. For more information about the play, see anationacts.brownvboard.org.

— Anna Perleberg