Since the 1980s, criminal investigators at the state, local and federal levels have used criminal profiling as a tool to narrow the range of suspects in a given crime. The work often takes investigators into one of the darkest places imaginable — the criminal mind.

"As a homicide investigator, you have to steel yourself and prepare yourself for the worst because that's the world you live in. You live with the worst of the worst, and you sit across the table from the worst of the worst," says Paul Dotson '81/02, WSU chief of police, who served with the Wichita Police Department from 1978-2002. For 12 of those years, he worked as a homicide detective, lieutenant and captain. "Your job is to get inside that mind. Often times it's a dueling of minds."

One of the many tools criminal investigators use to prepare for such duels is profiling, which, according to Brent Turvey, an Oregon-based forensic scientist and criminal profiler, combines elements of psychology, sociology, criminalistics ("the scientific study of recognition, collection and preservation of physical evidence as it is related to the law") and forensic anthropology. Stated simply, a profiler studies evidence left at a crime scene and attempts to formulate a portrait of the perpetrator based on that evidence. Profiling, like DNA analysis and the use of computers to develop national databases of offenders and crimes, is part of a two-decade growth spurt in science and technology in the field of criminal justice.

At any crime scene, careful investigators can glean information about a perpetrator's socioeconomic background (in the case of an item of clothing left behind), gender (in sexually motivated crimes) and racial identity (in the case of hairs left behind). And evidence Dotson refers to as "assaultive behavior," including exactly how a murder or an assault was conducted, provides clues into the makeup of the criminal's personality. "A perpetrator," he says, "leaves evidence of his pathology at a crime scene." For instance, the covering of a murder victim's face can suggest a close relationship between victim and murderer, or that the perpetrator identified with the victim on some level. Such behavioral clues arm investigators with information that can be used to search out and then interrogate suspects.

The FBI's approach to profiling was developed within the agency's Behavioral Science Unit, formed in 1974 at the FBI Academy in Quantico, Va. By the 1980s, profiling had been integrated into FBI training programs, and word of this tool and its uses had trickled down to investigators at the local level across the country. At the time, Dotson was assigned to the BTK Task Force, which was taking another look at Wichita's most notorious serial killer case, a string of murders that had taken place nearly a decade earlier. Because of so many advances in investigative techniques, it was, he notes, a fascinating time to be involved in law enforcement. In particular, the proliferation of profiling and computers (which allowed for the Automated Fingerprint Identification System, AFIS, a national registry of fingerprints collected at crime scenes, and the FBI's Violent Criminal Apprehension Program, VICAP, a registry of unsolved murder cases) laid the foundation for increased communication among police departments — and upped the odds on closing cases based on shared evidence.

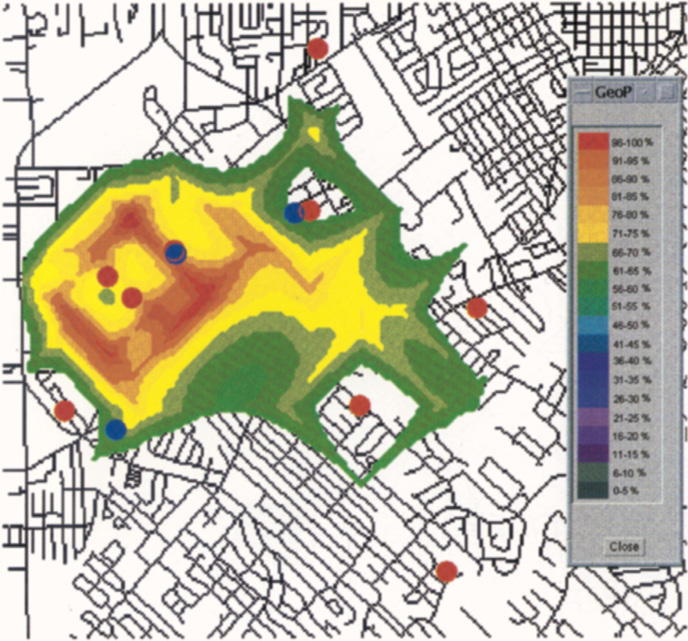

Rapist, reprinted with permission from Geographic

Profiling by D. Kim Rossmo. Since many criminals

seem to be most active in areas in which they are

comfortable, geoprofilers map out the perpetrator's

probable "confidence zones," what Rossmo calls

"jeopardy surfaces." Paul Cromwell, WSU criminal

justice professor and director of WSU's School of

Community Affairs, points to two locations that lie

within highly probable jeopardy surfaces, shown in red

and yellow in the above map. "The rapist lived here,"

Cromwell says, pointing to one site, "and worked here

— the sheriff's department. He was the sheriff's

deputy."

Although profiling and other new investigative tools did not lead to solving the BTK case, Dotson, who was a consultant on serial murder to FBI VICAP at Quantico, stresses that the wpd's implementation of such scientific advances did result in the department's maintaining an impressive close rate. "Our level of sophistication grew because of our interest in and use of the new techniques," he relates. "We saw not only an increase in clearance rates, but a better understanding of events. Homicide detectives trained in profiling seemed to grasp more quickly the type of investigation they'd found themselves in — the paths they could follow and the tasks they needed to perform."

FBI studies from the mid-1990s found FBI profiling techniques to be "of some assistance in 77 percent of cases." But profiling proved "to actually help identify the perpetrator" in only 17 percent of cases studied. Dotson points out that as new tools are developed and integrated into police procedures, older ones are being perfected. "We're constantly evolving," he says. "That's why it's important for officers to use logic and clear thinking in investigations."

Logic and clear thinking certainly abetted Thomas Bond, a police surgeon working in the late 1880s who is cited by some experts as the first profiler. Bond performed the autopsy on the last of Jack the Ripper's victims. From his observations of the Ripper's behavior, including wound patterns, Bond suggested investigators look for a quiet, inoffensive-looking man, probably middle-aged and neatly dressed, with "no scientific nor anatomical knowledge."

Suspicious Minds

In the United States, Howard Teten, a former crime-scene specialist, helped develop the FBI's approach to profiling, first taught by him in 1970 in an FBI National Academy course called Applied Criminology. To better understand criminal pathology, FBI agents were among the first to systematically interview offenders about their crimes as well as their personal backgrounds. Paul Cromwell, professor of criminal justice and director of the School of Community Affairs at WSU, also has gathered information from offenders to learn more about why and how they commit their crimes.

Cromwell, who edited In Their Own Words: Criminals on Crime and whose research specialties are gun violence, burglary and shoplifting, says although information gained from criminals can be useful, it's important to remember they are deceptive and, thus, information provided by them can be faulty. "If you interview someone in prison or in a probation office, they often tell you what they think you want to hear — and the way that things seem in their minds," he says. "They can give you all kinds of complex reasons for why they committed a crime, but if you ride around with them and ask, 'Why'd you do that house?' they might say, 'The garage door was open and there weren't cars there, so I just went in.'"

Cromwell says that, too often, a criminal needs only a small window of opportunity — that open garage door, a dimly lit house or a person who lives alone in a house on an isolated corner lot — to be enticed to carry out a crime. Understanding what triggers criminal activity is a key goal of his. Increased understanding of the criminal mind through more thorough studies of behavior assists investigators in their daily focus on capturing criminals, no matter their trigger or profile.

Michael Palmiotto, a WSU criminal justice professor whose academic interests range from human rights to statistics, explains profiling is a general term encompassing different types, including statistical, psychological, racial and geographic. Whatever the type, profiling is based on behavioral analysis, which is, Palmiotto notes, a fundamental aspect of all criminal investigations. That's why he says all police officers use "some form of profiling," whether formally trained or not. All officers analyze clues and attempt to link information that will close the circle of an investigation.

Although behavioral analysis can entail highly technical methodologies, Palmiotto points out that complexity is not necessary for success. He cites the story of a Georgia trooper who proved especially successful at making drug arrests. "He never took one class in profiling," he emphasizes. What the officer did was simply link what he knew –– drug traffickers were using a stretch of Georgia highway to move drugs from Florida to northern states –– to what he saw: an unusual number of cars with out-of-state plates and rental vehicles without passengers.

Geographic profiling is a recently developed form that uses complex mathematical formulas to map a criminal's "confidence zones." The theory, developed by D. Kim Rossmo, who is retired from the Vancouver Police Department and now a criminal justice professor at Texas State University in San Marcos, suggests criminals are most active in areas where they feel comfortable. By mapping a perpetrator's "confidence zones," Rossmo's method has allowed police to determine a criminal's home base within one square mile.

The Value of "Shoe Leather"

But for all the apparent exactness of profiling –– especially as portrayed in popular media –– a number of experts remain skeptical of its overall usefulness. Brian Withrow, WSU assistant professor of criminal justice, is one such skeptic. Withrow, who has worked as a trooper and inspector and who regularly lends analytical assistance to criminal justice agencies, says the true value of criminal profiling remains unknown. It is a tool, he says, that definitely has its pitfalls. He explains, "Police may tend to rely on a profile and think, 'Well, it's a white male, in his 40s, probably in the military.' That was the profile of the D.C. sniper. But as it turned out he didn't look anything like that: wrong race, wrong age."

Withrow adds, "Profiling creates a paradigm. Anything that doesn't fit can get discarded too fast. Police go looking for a white male and so this black kid must not be the guy, but in fact he is. I think a reliance on profiling limits observation skills. It can blind people."

Withrow is an unabashed fan of "old-fashioned" forms of investigation: interviewing witnesses, interrogating suspects, poring over evidence, tracking down leads. Solving crimes often comes down to what he calls "shoe leather." And he recounts a list of dangerous criminals apprehended during the course of routine police work, two of which are Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh, caught after being stopped by police for speeding, and abortion clinic bomber Eric Rudolph, who eluded FBI agents for years before being captured, scrounging for scraps of food, by a small-town rookie.

Withrow, Palmiotto, Cromwell and Dotson say nothing can replace the natural skills of a dedicated crime-fighter. But they also welcome the expanded role of science and technology in standard police investigations.

In the battle against crime, they say, every weapon counts.

Criminal Justice at Wichita State

Wichita State was only the fourth U.S. institution to offer college courses in police science. Established in 1934, the criminal justice program now features educational offerings taught by 11 faculty members whose collective areas of expertise cover the entire discipline. Criminal justice graduates work in fields as diverse as investigative reporting/journalism, social work and forensic criminology.

Students may earn either a Bachelor of Science or a Master of Arts in criminal justice. The program graduates roughly 110 students annually (of which 95-100 are undergraduates). There are approximately 450 criminal justice majors at WSU at the present time. The program is housed within WSU's School of Community Affairs, headed by criminal justice professor Paul Cromwell.

The Regional Community Policing Institute (funded by the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services and the U.S. Department of Justice and directed by Andra Bannister, associate professor of criminal justice and graduate coordinator) and the Juvenile Research Center are also housed in the School of Community Affairs.