The California condors near Big Sur perch in early morning and late afternoon in the tops of redwood trees. They survey the landscape with keen eyesight and a curious nature. Striking in black plumage and white underwing linings (visible only in flight), the giants can soar on thermal updrafts for hours, at speeds approaching 60 miles per hour and altitudes of 15,000 feet. They often mate for life, and their one chick per clutch is born with eyes wide open.

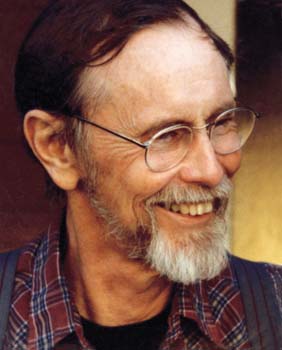

For five decades and counting, artist Bruce Conner fs '53 has been exploring some of our world's most soaring contraries: the sacred and the profane, good and evil, light and shadow, white and black.

Since leaving Wichita and alighting in San Francisco in 1957, he's been an influential figure in American art and film, his nylon-shrouded assemblages breeding international acclaim; his independent films capturing instant renown in avant-garde film circles; his work in so many forms (conceptual art, painting, drawing, sculpture, collage, assemblage, photography, printmaking and film) attracting large, if fractured, audiences. The wingspan of his body of work is stunning.

"Bruce Conner is an art-making machine," says Jim Johnson '75, an art historian and long-time Conner friend. "I don't think he could ever not make art." Conner's art resides in the permanent collections of museums from New York City, Chicago and Los Angeles to Paris, Vienna and Stockholm. He has received awards from the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Ford Foundation and others. His first film, A MOVIE (1958), was selected for the U.S. National Film Registry at the Library of Congress as one of the few American experimental films deemed "culturally, historically or aesthetically" important. Beginning to sound mainstream? Forget it.

"Art is an excuse for my behavior," Conner reports from the California home he shares with his wife of 47 years, Jean, also an artist. Often opting to work and play underground, Conner was a major player in the Beat, hippie and punk rock scenes. As Peter Byrne writes, "Pick a rebel art movement in Cold War America, and Conner was there." Conner says his affiliations with such groups were "necessary." He explains, "They were the ones who exhibited my work. I pounded and pounded on the mainstream door. I would have exhibited anywhere — in a gas station, if asked."

In 1990, he described his situation to Kristine McKenna: "The idea behind the story of The Emperor's New Clothes is central to my sense of aesthetics. I've seen foolishness all my life, yet for some reason we agree not to mention it. It amazes me how either through pure repetition or coercion by power, a view of what life is like is imposed on what life is like. I find it difficult to stand by and not speak of what's obviously going on, and this has been considered bad behavior on my part."

A few examples: He's withdrawn work from exhibition, destroyed work, refused to sign it, exhibited under false names (Dennis Hopper, Anonymouse and Emily Feather are three) and run for public office — delivering one campaign speech made up entirely of dessert names and another that quoted passages from the Bible that read, in part: "The light of the body is the eye: therefore when thine eye is single, thy whole body also is full of light; but when thine eye is evil, thy body also is full of darkness."

A few examples: He's withdrawn work from exhibition, destroyed work, refused to sign it, exhibited under false names (Dennis Hopper, Anonymouse and Emily Feather are three) and run for public office — delivering one campaign speech made up entirely of dessert names and another that quoted passages from the Bible that read, in part: "The light of the body is the eye: therefore when thine eye is single, thy whole body also is full of light; but when thine eye is evil, thy body also is full of darkness."

The thing that stamps his antics as uniquely Connerly is how deeply thought-out they are. Not to mention funny. When, for instance, he quit signing his 1950s oil paintings, he did so because he wanted viewers to appreciate the essence of the work itself, not view it as a "labeled" product. After he relented and began signing his works again, he did so in the most obscure position he could find, in the smallest script he could manage. He then made and provided signature-locator maps. His sense of humor has been variously described as sly, outrageous, juvenile, dry. How does he describe his humorous side? "He's always standing next to me."

Born in McPherson, Kan., in 1933, the oldest of three siblings, Conner grew up in Wichita. In a 1986 interview with Peter Boswell, one of three curators for the Walker Art Center's showing of 2000 BC: The Bruce Conner Story Part II, the solo exhibition that offered the first comprehensive look at his work, Conner related, "By the time kids are 7 or 8 years old, in general, they have been indoctrinated into peer pressure and badgered into seeing 'reality' in a certain way — reality being whatever you are badgered into believing." Conner resisted badgering.

At the age of 11, he had a spontaneous mystical experience. Lying on the floor of his room one afternoon he "changed and grew old, through all kinds of experiences that seemed to last for centuries or thousands of years, in worlds of totally different dimensions. Then I became aware of myself being in the room. Here I am, and I'm enormously old. How can I ever get up? I'm practically disintegrated. I'm an ancient person. My bones are falling apart. I can't move. Then I slowly become aware of the rug. I look at my hands, and they're not old." He later recalled thinking, "There were so many things that were unknown secrets, that adult society knew, that they didn't let children know about. I thought this was one of them."

Conner put himself in the role of an artist quite early on. His sister Joan, three years his junior, recalls: "Today, we'd probably call them 'acting' classes, but our folks sent us to 'expression' at the Eaton Hotel. I was about 8, and I remember being Little Miss Muffet. Bruce was a grand artist." Joan also recalls a family-initiated, linoleum-block art project. She tooled a jonquil (even though she liked horses better), while her big brother made "a Pony Express rider on a horse at a fast run. He used lines to indicate speed. There's sagebrush and part of a skull — but the skull might just be in my imagination."

BREAKAWAY (1966 FILM)

Generally speaking. There must be other shifts.

- Samuel Beckett, The Unnamable

A treetop survey of Conner's wider world in the post-WWII era presents a diverse view. In NYC the canonical Beat authors, Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs, met — and abstract expressionism spilled, splotched and dripped its way into art history. The United States was economically booming, while Europe sifted through its ruins. Mass-produced television sets flickered on in an ever-growing number of U.S. households, although Conner did not bring one into his until 1959. While TVs were broadcasting cathode-ray tube images of everything from Elvis and Marilyn to nuclear-test explosions on Bikini Atoll (launching the Cold War), Conner gleaned from movies many of the images that became cultural icons.

Wichita was a midsize city of about 150,000 people. Sharing an ascetic religious tradition and a Western pioneer heritage, most Wichitans were gut-level conservative. Conner describes himself as "just plain conservative," adding that the conservative values he holds dear include individual rights and "conserving history." Growing up, he felt alienated and identified with those outside the cultural norm. "In general," he says, "if you were interested in art, you were outside the social web." Small enough to be repressive, Wichita was large enough to produce a few kindred spirits. At East High School and then the University of Wichita, Conner connected with a fluid group that ebbed and flowed with such mercurial personalities as Michael McClure fs '52, David Haselwood '53, Corban LePell '57/59, Lee Streiff '55, Jim Lyle '54 and John Pearson '55. Art, music, literature, philosophy, sociology and politics were favorite group concerns. "We took our interests very seriously," says LePell, a California State University-Hayward art professor, now semi-retired.

"When Bruce entered Wichita University in 1951," Johnson says, "he brought with him the influence of his art studies with East High instructor Watson Bidwell, an advocate of abstract art and one of Bruce's first influences in modernism. Bruce and Michael (McClure) shared an interest in abstract expressionism — the paintings of Jackson Pollock and William Baziotes, especially, at that time. In my opinion, one of the greatest gifts that members of the WU art faculty gave students like Bruce who were working in that vocabulary was, simply, acceptance."

Says Conner, whose paintings include OLD NOBODADDY (from the collection of Joan Conner), "I remember two professors and an instructor who were supportive of my work — David Bernard, Robert Kiskadden and Reed Rogers." Johnson adds, "The evolution of Bruce's style of painting was from a loose to a more hard-edge abstraction. His best paintings are in that character."

Conner's work at WU included at least one unauthorized creation. LePell explains, "One old-school instructor taught in a room upstairs. Bruce and I bought some knitting yarn in all different colors, and we filled that room with it. No one could get in." Conner says, "I think the art department called it a prank. It was more of a re-design of the classroom, making it not very functional. I personally was trying to use the yarn like a spider web — attaching it to chairs, windowsills and fixtures. Corban's approach was more like tossing a basketball. It took more time to take down than to put up."

Lyle, a WU philosophy graduate and retired designer, remembers a special Conner talent: "After a Friday afternoon drinking beer at the Golden Pheasant Bar, we would all agree on whatever 'revival' that might have thrown up a tent, send Bruce ahead and alone, and then the remainder of us would arrive in small numbers and different cars, take seats in scattered locations in the audience and wait for the altar call. You see, Bruce could cry at will. He was glorious. No one 'got saved' with anywhere near the frequency and the style that attended Bruce's performance."

Streiff, a retired Wichita educator and editor of the Provincial Review, a literary magazine begun at WU in 1952, laughs and admits to being among the revival-goers. "Bruce was young, brash, off-the-wall," he says. "He went through phases. There was a Jerry Lewis phase, for instance." Streiff adds that Conner, if not genuinely moved to repentance, was truly inspired by music, gospel music in particular, with its rootedness in the sacred and in African-American culture. In 1961, Conner created a pair of works (the film COSMIC RAY and the assemblage RAY CHARLES/SNAKESKIN) as an homage to Charles, the gospel-inspired rhythm-and-blues artist whose music commingled the spiritual and the worldly. To this day, there sits somewhere among Conner's possessions an unfinished documentary film about the black gospel quartet, the Soul Stirrers.

LIBERTY CROWN (1967 FILM)

Whether all grow black, or all grow bright, or all remain grey, it is grey we need, to begin with, because of what it is, and of what it can do, made of bright and black, able to shed the former, or the latter, and be the latter or the former alone.

- Samuel Beckett, The Unnamable

After the spring semester of 1953, Conner winged his way via Continental Trailways bus from WU to the University of Nebraska, where LePell had taken up studies and from which Conner earned a BFA in 1956. Conner continued his studies at the Brooklyn Museum Art School. When Rebecca Solnit, author of Secret Exhibitions (1990), asked him why he attended college for so long, he answered, "Going to college kept you out of the army. I had a tremendous horror of going into the army." Draft-age during the Korean War and a 12-year-old when atomic bombs incinerated Hiroshima and Nagasaki, he also had a dread of nuclear war.

Conner abandoned his formal education at the University of Colorado, Boulder, where he had joined his future wife, Jean Sandstedt. They married in 1957 and, after hearing from McClure about the vibrant art scene in San Francisco, boarded a plane for the West Coast. McClure and his wife Joanna put the newlyweds up at 2324 Fillmore while they looked for a home of their own, which they found around the corner on Jackson Street.

Conner aligned himself with a group of radically innovative artists, including (in addition to McClure and Haselwood) Jay DeFeo, Wally Hedrick, Joan Brown, Manuel Neri, George Herms and Wallace Berman. As different as their individual takes on art and life, each was interested in expanding perceptions, breaking through both artistic and social conventions — and having a good time.

Toward at least a few of those ends, Conner founded the RAT BASTARD PROTECTIVE ASSOCIATION, a by-invitation-only group whose meetings were primarily parties in one another's studios. The name has three wellsprings: the slang term "rat bastard" (which McClure seems to have been the first in the group to pick up), the 19th century's Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the Scavengers Protective Association, an organization of San Francisco garbage collectors. In 1983, Conner told Boswell, "I decided, we'll have the RAT BASTARD PROTECTIVE ASSOCIATION: people who were making things with the detritus of society, who themselves were ostracized or alienated from full involvement with the society."

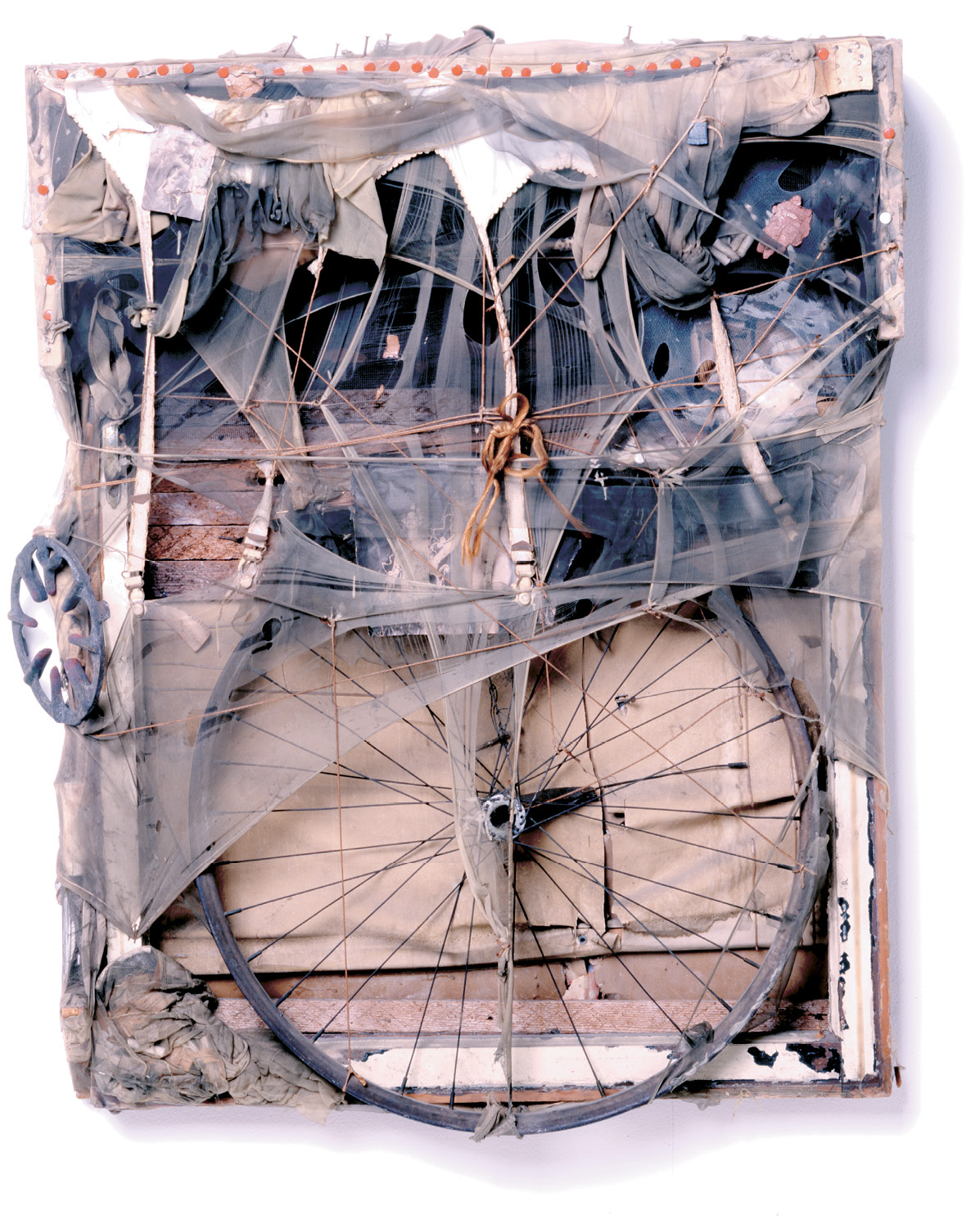

A prolific painter, Conner by and large had left the medium behind by the late 1950s. In his assemblages and films of the period, he often dealt with death and sex together. His works are tinged with his fascination with fragility, absurdity, texture, pattern and mind-blowing detail. He scoured his environs for raw materials for assemblages: scraps of wallpaper salvaged from derelict buildings, the spoked wheel of a broken bicycle, cast-aside costume jewelry, the feathered wing of a bird. From such disparate parts, he concocted wholes that observe rapacious sexuality and reflect the unmistakable stench of death. McKenna writes, "Alarmingly morbid in the early years of his career, Conner turned out work that pulsates with futility and a sense of entrapment evocative of the writings of Samuel Beckett."

A typical viewing of a Conner assemblage, such as SPIDER LADY, occurs in stages: being enticed to look more closely, inspecting it from every angle and discovering, often with a jolt, the secret behind veils of nylon — a doll's head with a nail driven into its forehead, for instance, as in SPIDER LADY HOUSE (1959). Because of this engaging but fragmented process, the narratives of Conner's works are purposefully ever shifting and highly dependent on the viewer's personal perspectives. Streiff comments, "What lies behind the image is what Bruce is attracted to."

Conner's longstanding identification with society's outcasts and his passion, from childhood, for casting light on society's secrets fused in the creation of CHILD (1959). A horrific figure in wax of an abused child (with adult genitalia) strapped in a high chair and cobwebbed in nylon, CHILD was inspired by the case of Caryl Chessman, a convicted robber-rapist sentenced to death for kidnapping and later gassed by the state of California. CHILD darkly juxtaposed the chaos of Chessman's uncontrollable impulses and society's need for order and control. When the work was first exhibited, a San Francisco Chronicle reporter ranted, "CHILD is something a ghoul would steal from a graveyard." It is also, Conner says, "something society creates everyday." Conner's methods of social commentary hark back to those of Jonathan Swift, the 18th-century Irish prose satirist who in 1729 recommended with horrifying logic that Irish poverty could be eliminated by breeding children as food for the rich.

BLACK DAHLIA (1960) is another of Conner's more lurid assemblages. A visual narrative of a grisly 1946 Los Angeles murder, the work is described by Boswell like this: "The convergence of the image of a scantily clad woman submissively offering her back to the viewer, a back into which nails have been driven, presents a viscerally conflicted image of aggression and victimization, eroticism and naked brutality." In 1974, Conner explained to Paul Karlstrom: "I felt this was like performing a play. It was theater. I was using objects and photographs and endowing them with character. But when I exhibited, people would project on to me the violence of these pieces."

Conner's assemblages are acknowledged by art-world insiders as helping break the stranglehold abstract expressionism held on art during the 1950s. Conner himself wants it understood that "abstract expressionism is not my enemy. It's never been explained to me why all these things can't exist together."

Another of his creative endeavors (short films that use pop music as sound tracks, such as the Beatles' "Tomorrow Never Knows" in LOOKING FOR MUSHROOMS, 1961-67) is hailed as precursors of music videos and a major influence on MTV. "Not my fault," the artist has said. Many of his films became instant classics because he constantly broke new ground — as an artist and a social critic. For example, the protagonist of A MOVIE is The Bomb. Spliced together from bits and pieces of stock footage, the 12-minute montage of disaster scenes also includes snippets of a girlie movie and countdown leader (those flashing numbers leading to the beginning of a movie, something viewers are not supposed to see). Bruce Jenkins, director of the Harvard Film Archive and curator of the film exhibits in 2000 BC, writes, "What the Cubists wreaked on painting, Conner inflicted on cinema."

Conner's obsession with the hidden workings of image and perception, found in all of his work, is in his films especially tied to such sight-and-mind concepts as phi phenomenon, an illusion whereby still images are combined by the brain into surmised motion; flicker fusion, the frequency at which the flicker of an intermittent light stimulus appears to disappear (the fusion threshold is 16 frames a second; modern film runs at 24); and the persistence of vision, which refers to afterimages, or the retina's retention of an image for a split second longer than it is actually there. Conner simply revels in playing in such realms. Yet his play, lit with humor as it is, is fully capable of dark commentary on such social issues as militarism and the objectification of women, two of his central themes.

Conner's longtime friend Dennis Hopper has told many people, "Bruce's movies changed my concept of editing. In fact, much of the editing of Easy Rider came directly from watching his films." Conner later did pre-production work on Peter Fonda's The Hired Hand and returned to filmmaking to do rock films of Devo and for David Byrne during punk's heyday, but, like assemblage, which he gave up in 1964, film did not arrest his far vision.

CROSSROADS (1975 FILM)

I shall never be silent. Never.

- Samuel Beckett, The Unnamable

Thinking to escape the devastation of the bomb surely soon to drop, the Conners moved in 1961 to Mexico, where Jean gave birth to a son. Conner's assemblages took on different textures and patterns. A new trend in his drawings — patternings so tiny and dense that they seem to skirr across the page — can be seen in later works such as 23 KENWOOD AVENUE (1963) and MAZE DRAWING (1965), which resembles flowing water or fractal colonies of bacteria. Rooted in Asian art, the drawings glance from the micro- to the macrocosm and back again.

They returned to the States, staying first in Wichita and then, by invitation of Timothy Leary, back East before resettling in San Francisco, where Conner would "work on projects all day long and well into the night," he says. "By the end of the '60s, I'd developed so many dimensions of myself that I had 15 personalities at war trying to dominate this body. I finally managed to shut the voices up, mostly by ignoring them."

In 1967, Conner dropped out of "the art business" for four years. He worked at odd jobs and with the North American Ibis Alchemical Light Co., making light shows for rock concerts. When punk rock became conspicuous, he frequented San Francisco's Mabuhay club, drank heavily and photographed the musicians for Search & Destroy magazine. The private Conner continued making objects, including his ANGEL series of 29 life-size photograms (1972-75), and densely patterned drawings of the night sky, his STAR series.

In a recent Artweek review of Conner exhibitions at the Michael Kohn Gallery in Los Angeles, Peter Frank chose two terms used to describe Picasso — "pathologically inventive" and "genius" — and reassigned them: "The same can be said about Bruce Conner, whose accomplishments have rarely been undervalued, but have usually been undercounted." He continues, "His restlessness is clearly more purposeful, if no less fecund, than Picasso's." Conner's restlessness has embraced — in addition to the far-ranging objects mentioned — sculpture, ink-blot drawings (some so precisely ordered they resemble architectural structures) and engraving collage. (Outside the visually based, there's his harmonica playing, but that's another story.)

Exhibited at the Kohn Gallery in back-to-back showings, Conner's work from the past two years combines and re-presents images and subjects from earlier work. CROSSROADS (1975), an "ominous but lyrical meditation on annihilation," as Frank describes it, and an expanded LOOKING FOR MUSHROOMS were shown. (Both are newly available on DVD.) Among the still-work were tapestries, jacquard rugs produced in Belgium that reproduce Conner's 1980s black-and-white collages based on engravings depicting scenes from the life of Christ.

As varied as Conner's career is, one constant has been collaboration. He's made drawings with LePell, asked fellow filmmaker Bob Branaman fs '59 to shoot some of the footage in LOOKING FOR MUSHROOMS and fellow-artist Pearson to assist with the production of the 13-canvas work TOUCH/DO NOT TOUCH (1964). He's worked with McClure and Haselwood on many projects, was Streiff's co-editor for the Provincial Review, when it was finally published in 1996, and in 2002 illustrated the Arion Press publication, The Ballad of Lemon and Crow by Glenn Todd '58.

A survey of Conner's works is more like looking at a group show than the products of one mind. Conner's old friend McClure calls them "healthy, creepy, dark, sweet, laughing works of art." They are contrary, like Conner himself. As frenetic a character as he may seem in print, in 1976-77 he toiled over only one piece, the last of his STAR drawings, LAST DRAWING. It is rendered in black and white with such density and fineness that it appears as immense and indeterminate as our universe. And it conjures such an aching for sureness, for truth, you may want to escape its intensity. When from behind closed eyes, you see the very same image, the laugh you'll hear is Conner's.

The laugh of a most contrary man.